The coin flip that saved baseball in Seattle

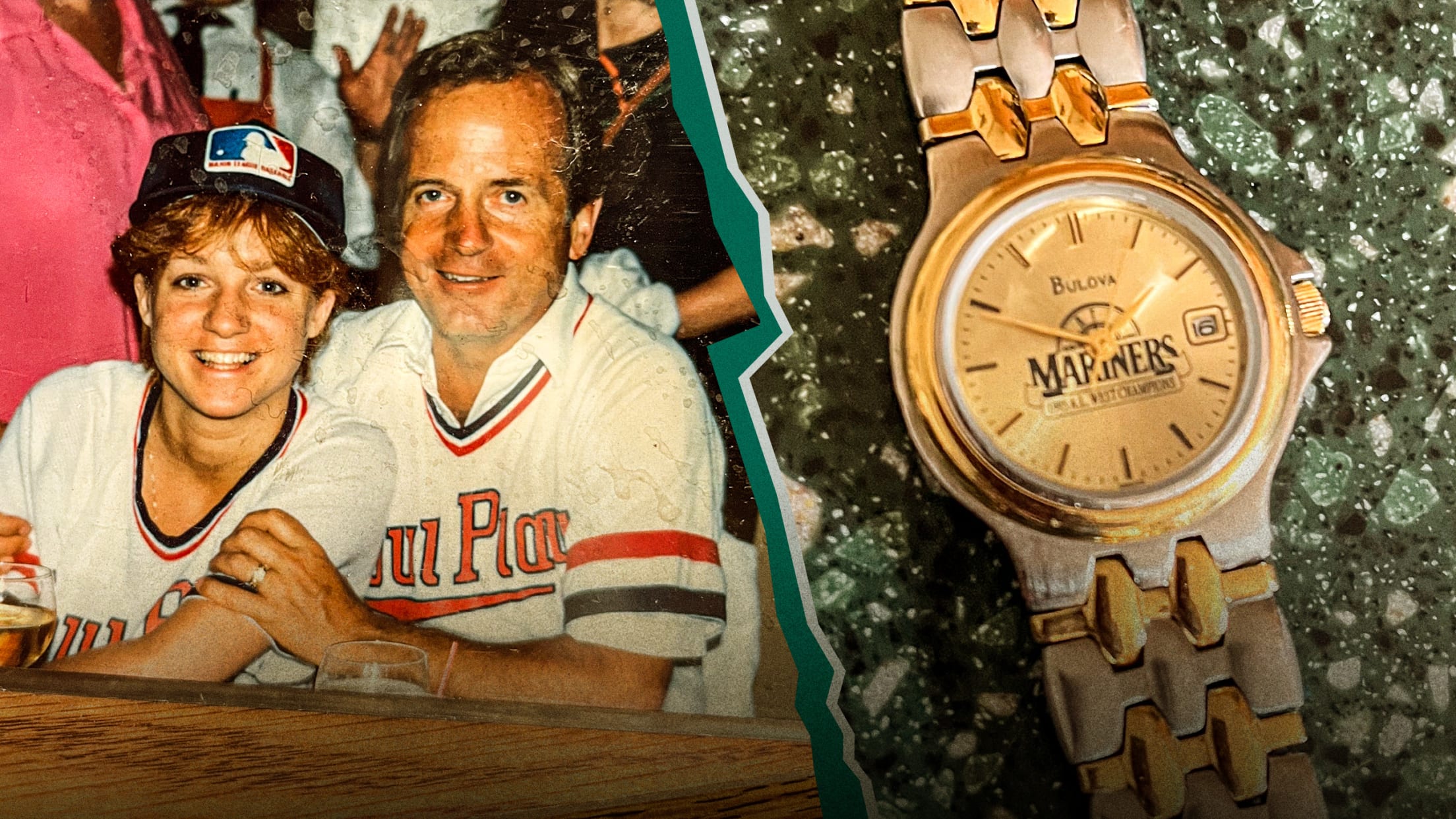

The two-tone Bulova watch sat untouched in a dresser drawer in Metuchen, N.J., for many years. Yet much like its owner, it came through when called upon.

Carolyn Taylor had received the watch as a gift way back in 1995 and had not worn it in quite a while. But one February day earlier this year, her sister, Laurie Holmes, called with a request while en route from Chicago.

“[Holmes] had left her watch at home,” Taylor recalls. “She called from the airport when she realized she [had forgotten to] wear one. She said she’d need [to borrow] one when she landed.”

Taylor instantly remembered the watch she had stashed way for safekeeping. She retrieved it from the drawer and ran out to a Walgreens to get a new battery for it. And just like that, after all those years of quiet confinement, the second hand clicked back to life and began to rotate around the dial’s decoration:

A Seattle Mariners logo, adorned with a banner declaring the team the “1995 A.L. WEST CHAMPIONS.”

Carolyn Taylor was not a member of the 1995 AL West champion Mariners. She did not work for the Mariners. She was not a Mariners fan. And as of that year, she had never even been to Seattle.

So why does this random New Jersey woman have in her possession a watch celebrating the team’s 1995 division title?

Well, because, in a weird way, Carolyn Taylor is the reason the Seattle Mariners still exist.

* * *

With the Mariners and their fans swept up in their first playoff run in forever, this is a fun time to look back on the club’s first playoff run ... ever.

It was a run made possible, in part, by a quirk in the MLB postseason format that ceased to exist in 2009, and by a tiebreaker system that ceased to exist here in '22.

Let’s go back, specifically, to Monday, Sept. 18, 1995, for that, we can say with the benefit of hindsight, is a day as important as any in the story of how the Mariners secured their first division title and, eventually, their second stadium.

When dawn broke on that date, the state of the Mariners franchise was simultaneously promising and precarious.

On the promising side was the baseball itself.

The ‘95 Mariners had a ton of talent. Center fielder Ken Griffey Jr. was 25 years old and already in his sixth All-Star season. Randy Johnson was on his way to his first of five Cy Young Awards. Designated hitter Edgar Martinez, first baseman Tino Martinez, right fielder Jay Buhner and third baseman Mike Blowers provided big power. Alex Rodriguez was getting his feet wet as a rookie. And in Lou Piniella, the M’s had a skipper with World Series-winning pedigree.

Though the ’95 season had been a trying one -- thanks in large part to Griffey fracturing his left wrist on one of his dynamic catches at the wall in May and missing nearly three months -- the club was hitting its stride in the home stretch. Seattle had been in last place in the AL West at the All-Star break, but the M’s hung in there enough to earn the support of the front office, which added starter Andy Benes at the Trade Deadline. Griffey’s Aug. 15 return to the lineup was coupled with the trade acquisition that very day of leadoff hitter Vince Coleman. And over the course of the next five weeks, the Mariners whittled a 12 1/2-game deficit in the AL West race with the first-place Angels down to just three games, while also taking a one-game lead over the Yankees in the race for the AL’s newly created Wild Card spot.

“Seattle had never made the playoffs,” second baseman Joey Cora told MLB.com in 2020. “But once we got closer to the Angels, they were coming down, and we were going up. It was that simple.”

Another simple equation: As the wins piled up, attendance picked up.

The Kingdome -- a multipurpose facility better suited for football -- had spent the previous 18 baseball seasons building a reputation for small crowds and unfavorable sightlines. But suddenly, it was infused with life, energy and joyful noise.

“People got really serious,” says Rick Rizzs, the Mariners’ longtime radio broadcaster. “In September, we went from drawing maybe 12,000 or 15,000 fans to drawing 20,000 or 25,000, and then 50,000. From the middle of September, you could not hear yourself talk.”

That’s not an exaggeration. In back-to-back wins over the Twins on Sept. 12 and 13 to pull within five games of the Angels, the Mariners drew 12,102 and 16,469 fans, respectively. They then hit the road for a weekend series in Chicago and returned on our notable date of Sept. 18 for a home game against the Rangers that drew 29,515. The last five games of that final homestand, in which the M’s won seven of eight games, would have an average attendance of 49,990.

Rizzs remembers watching a local TV report from Pioneer Square around that time in which a reporter asked a passerby, “When did you become a Mariners fan?”

“Thursday,” the man replied.

Rizzs laughs at the memory.

“I was thinking, ‘Well, we’ll take it,’” Rizzs says. “We’ll take that guy, and we’ll take the other 30,000 or 40,000, too.”

Fan support is always important in professional sports. But for the Mariners at that particular time and that particular week, it was critical.

Just 14 months earlier, Mariners team president Chuck Armstrong had been at his son’s Little League All-Star Game when he got a call from his secretary, telling him there was a “problem” at the Kingdome.

“We don’t have problems,” a cheery Armstrong said. “We either have challenges or opportunities.”

That’s when his secretary told him the Kingdome’s ceiling was falling apart.

“Oh,” he responded. “You’re right. That is a problem.”

A definite problem. The Kingdome had to be closed when four ceiling tiles fell nearly 180 feet into the stands behind home plate. The team was forced into a 22-day road trip before the season was cut short by the players’ strike. (Had the strike not intervened, Armstrong says the Mariners may have had to play “home” games in Oakland or Anaheim.)

It ultimately cost $51 million to shore up the Kingdome ceiling, and two workers were killed in a crane accident during the cleanup. The building’s other tenants -- the NFL’s Seahawks -- played their first three regular season home games of 1994 at the University of Washington’s Husky Stadium before the Kingdome finally reopened on Nov. 4.

When the baseball strike ended in the spring of ’95, it was clear that the Mariners would soon need a new home, even though the Kingdome, which had opened in 1976, was still not paid off.

King County owned the Kingdome. The county’s executive task force had determined that, for a new baseball-only stadium to be constructed, the public would have to foot 65 percent of the bill, which was estimated to be between $250 million and $275 million. The Washington state legislature approved a funding mechanism that would raise the King County sales tax from 8.2 to 8.3%, but the measure would have to be approved by voters.

The vote was to be held on Tuesday, Sept. 19.

That was the precarious side of the equation. If the plan did not get approved, the threat of the franchise being sold and moved to another city loomed large.

“We started in that period [with the] prediction that it was going to fail,” then-Mariners chairman John Ellis told MLB Network in 2019. “But if we could change the public perception on the team, maybe that could cause the vote to pass.”

Sept. 18 marked the final day of campaigning for the ballot issue. And the ballclub did its part, with Johnson overpowering the Rangers and Blowers and Edgar Martinez both going deep in an 8-1 victory that pulled the M’s within two games of the Angels.

But while the Mariners were focused on winning a game and winning a vote on Sept. 18, they were also involved in another contest -- of underrated importance -- that took place that same day, nearly 3,000 miles away.

It all came down to the flip of a coin.

* * *

Though the Boston Red Sox and Cleveland Indians essentially had their division titles sewn up by Sept. 18, there were six other AL teams -- the Mariners, Angels, Yankees, Royals, Rangers and A’s -- within six games of undecided playoff spots entering play that day.

Each of those teams was to be involved in what was, at the time, an annual September exercise used to determine the sites of potential tiebreaker games -- the coin toss.

Coin tosses once had a fairly important influence on October outcomes.

Way back in 1946, the Brooklyn Dodgers won a coin toss against the St. Louis Cardinals to determine home-field advantage in a best-of-three tiebreaker series. The Dodgers opted to play the first game on the road and the final two at home. They then lost the first game and went on to lose the series.

So five years later, ahead of a 1951 tiebreaker series against the New York Giants, the Dodgers made the opposite decision when they again won the toss. This time, they opted to host Game 1 and travel for Games 2 and 3 -- a decision that would also come back to bite them, when a Bobby Thomson home run in Game 3 that would have been an out at Ebbets Field sailed into the lower left-field seats at the Polo Grounds.

Similarly, Bucky “Bleeping” Dent’s historic home run for the New York Yankees in the 1978 AL East tiebreaker against the Boston Red Sox cleared Fenway Park’s Green Monster but would have been an out at Yankee Stadium. Losing the coin flip arguably helped the Yankees win the game.

The 2007 Colorado Rockies had the superior head-to-head record against the San Diego Padres but only got to host that year’s NL Wild Card tiebreaker because they won the coin toss. And that’s how Matt Holliday got to score the winning run in the bottom of the 13th by (maybe) touching home plate.

All told, coin tosses decided the home-field alignment for 12 tiebreaker games/series from 1946-2008.

The practice was ultimately abandoned in 2009, when MLB opted to have home-field determined by head-to-head records.

This year, tiebreakers themselves have been abandoned. Under the expanded MLB postseason format introduced for 2022, ties are to be settled based on regular-season results, with head-to-head records being the first deciding factor. With 12 total teams now advancing to October, the league opted to let math -- not Game 163s -- settle any unresolved issues so that the postseason schedule is not held up an extra day.

Back in ’95, though, tiebreakers were still on the table ... as were the bouncing coins.

Because the American League and National League still operated somewhat independently of one another at that time, the AL coin tosses -- 18 in all -- were to take place in the office of AL president Gene Budig. Each team would have a representative on-hand to witness the toss of the coin, which was usually a quarter.

“There was a very complicated formula in the league rules that said you draw lots to determine Team A, B and C, depending on how many ties were possible,” says Phyllis Merhige, a longtime MLB executive who at the time was the AL’s director of public relations and who was in the room for many coin tosses. “So [in a three-way tie], maybe A gets a bye while B plays C. It was a whole complicated thing. And then we’d do the coin flip, and, if you won the flip, you decide whether you would want to host [a tiebreaker] or not.”

Because the vast majority of races were settled without need for a Game 163, it’s not as if clubs dispatched high-powered execs to midtown Manhattan in mid-September to call out “Heads!” or “Tails!” Other than George Steinbrenner sending a team rep as a matter of course (and partial paranoia) whenever the Yankees were involved, clubs were typically content to let a league executive or public relations person represent them.

But for the ’95 toss -- the first of the Wild Card era -- Armstrong pulled out a slight wild card of his own: He wanted Carolyn Taylor, then the director of special events for MLB, to represent Seattle.

“To call somebody from special events was definitely unusual,” Merhige says. “Only Chuck. That’s Chuck.”

Armstrong chose Taylor not because she had any tie to the team or to the city and not because she had any track record of winning games of chance.

No, he chose her because, when the two had met (either at MLB headquarters or the Winter Meetings ... neither remembers exactly), she had been introduced to him as a fellow Purdue grad.

That had been enough to win him over.

“I didn’t want somebody from the baseball [executive] side,” Armstrong says. “She just seemed like a logical pick to me. She was someone I knew and liked.”

Taylor was floored -- and nervous -- to be entrusted with such a responsibility.

“I needed Phyllis to calm me down beforehand,” she recalls.

She also needed some guidance from Armstrong.

“I can’t make the call,” she remembers telling him. “This is a major decision. What do you want me to call? Heads or tails?”

Armstrong, having done some research on how to gain a small-but-perhaps-sufficient edge in coin tosses, gave her the following instruction:

“Watch the coin flip before ours,” he told her. “Find out which is on top of the thumb -- heads or tails. And then, whatever it is, when it lands on the table or the floor or whatever, if it’s heads and then lands heads, call what’s on the top. If it’s the opposite, call what’s on the bottom.”

How often would such a scheme work?

Well, it’s a coin toss, so … probably half the time.

But on this day, in this moment, in the only one of the tosses that would turn out to be necessary (the one determining home-field advantage if the Mariners and Angels finished tied atop the AL West) and with the fate of Seattle baseball on the line, it worked wonderfully.

Did Taylor call heads or tails before that quarter was flipped? All these years later, she understandably can’t remember. All we know for sure is that she won the toss and elected to receive (the home game).

“We sent her flowers,” Armstrong says.

And then it was back to baseball. And the ballot.

* * *

The following day, the Mariners won.

And lost.

The game the night of Sept. 19 against the Rangers was a thriller. The M’s were down, 4-1, going into the bottom of the eighth, but a Griffey leadoff home run over the high wall in right pulled them within two runs. In the ninth, pinch-hitter Doug Strange hit a two-run shot to right to tie it. And in the 11th, with two on and two out, Griffey lined a single to left off the glove of Rangers third baseman Luis Ortiz to give the Mariners the 5-4 victory.

While this was going on, the ballot results were coming in. Much like the game against the Rangers, it, too, was a close and dramatic affair, with the stadium approval initially trailing, then pulling into a dead heat. And just as the Mariners pulled off their extra-inning win deep into the night, a bulletin came out that the issue appeared to have enough votes to pass.

At FX McRory’s, a steakhouse and bar near the Kingdome, strangers hugged and celebrated. Armstrong and other Mariners executives rolled in after the game and were treated to a champagne toast. Not only was the team now within one game of first place, but it would soon have the new home it needed to stay in Seattle.

Until ...

“At 4 o’clock in the morning,” Ellis said, “I get a phone call at home. ‘The absentee ballots are coming in now, and it’s going to fail.’”

It took a week to confirm, but, once the roughly 47,000 write-in ballots had been counted, the stadium issue indeed had been defeated.

All told, 491,918 ballots were cast. The issue lost by just 1,082 votes.

With that, Ellis wrote letters to local politicians to inform them that, if a new plan was not in place by Oct. 30, the ownership group led by Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi would be putting the team up for sale.

Though the ballot issue failed, the Mariners themselves refused to lose. In fact, that was their motto -- “Refuse to Lose.” It was printed on T-shirts and banners and became a rallying cry.

[INTERESTING SIDE STORY 1 OF 2: To make the “Refuse to Lose” T-shirts, the Mariners paid $25,000 to a man in South Carolina who had registered the phrase. But they were sued by then-University of Massachusetts men’s basketball coach John Calipari, who alleged that he had bought the trademark from the man in South Carolina. Ultimately, the suit did not go anywhere. But years later, Armstrong was attending the Kentucky Derby when he was introduced to Calipari. “I’ve wanted to meet you for years,” he told Calipari, who was now the coach at Kentucky. Calipari initially assumed it was flattery. “No,” Armstrong said, “you sued me!” Armstrong told Calipari the story, and the two had a laugh about the situation. Then, in front of a suite full of Churchill Downs witnesses, Calipari shook Armstrong’s hand and announced the legal matter was settled. A short time later, he mailed Armstrong a Kentucky T-shirt bearing the phrase “Refuse to Lose.”]

The Mariners did refuse to lose ... until the last two games of the regular season, in Texas. They had not only caught the Angels but taken a two-game lead in the West with two to play. But they dropped the penultimate game of the season, 9-2, and they lost the finale, 9-3. The Halos, meanwhile, won back-to-back games against the A’s.

So the season ended with the AL West in a two-team tie.

And you know what that meant. Suddenly, that Sept. 18 coin toss was relevant.

The Angels had won the season series against Seattle, 7-5. But because of Carolyn Taylor’s heads-up (or maybe it was tails-up) performance in the A.L. office, the Mariners got to host the Oct. 2 tiebreaker tilt.

To say Seattleites were ready to host Game 163 is an understatement. On extremely short notice, with just 22 hours between the regular-season finale and the start of the tiebreaker, they sold out the Kingdome. A crowd of 52,356 showed up, ready to roar.

“It was electric,” Armstrong recalls of the atmosphere. “It’s hard to describe the noise and the sound.”

Given the acoustics of a full Kingdome and the energy that had been built up as a fruitless franchise finally found itself hosting an October game, this was a distinct home-field advantage. The coin flip had done them quite a favor.

Of course, having the Big Unit on the hill didn’t hurt, either. In a delicious subplot, Randy Johnson was matched up against the Angels’ Mark Langston -- the pitcher the M’s had dealt to the Expos in 1989 in the trade that brought them ... Randy Johnson.

Johnson stifled the Angels’ bats with one of his best performances of the season. The Mariners took a 1-0 lead into the seventh inning, where they had the bases loaded against Langston with two out.

All these years later, Rick Rizzs recites his call of the following pitch to Luis Sojo from memory:

“Swing and a ground ball, sneaks on by [Angels first baseman J.T.] Snow, down the right-field line to the bullpen! Here comes Blowers! Here comes Tino! Here comes Joey! The throw home, cut off by Langston, the relay home gets by [catcher Andy] Allanson! Cora scores! Here comes Soto, Soto scores! EVERYBODY SCORES!”

Johnson went the distance in what turned out to be a 9-1 victory, and that’s how the West was won. The Mariners were not only division champs for the first time in their 19-year history, but they became just the second team in MLB’s Divisional Era -- joining the 1978 Yankees -- to win a division they had trailed by at least 13 games in the second half.

No one has done that since.

The ’95 playoff format gave the division-winning M’s home-field advantage against the Wild Card-winning Yankees in the best-of-five Division Series, yet with the disadvantage of having to play the first two games on the road. The Mariners lost both of those games, but they returned to the cacophonous Kingdome to win Games 3 and 4. And then, trailing by a run with two on in the bottom of the 11th inning of Game 5, Martinez had the seminal moment of his Hall of Fame career by hitting “The Double,” scoring Cora from third and a hustling Griffey with the game-winning run from first for one of the great endings in postseason history.

Though the Mariners wound up losing to Cleveland in the AL Championship Series, the run to October had done its part to compel civic leaders in Seattle and the state of Washington to come up with a solution to the stadium issue.

Governor Mike Lowry called an emergency session of the state legislature in early October. Ultimately, an alternate means of funding a new stadium with public money was proposed. The Washington Restaurant Association broke a legislative deadlock by accepting a half-percent tax on food and beverage sales in restaurants and bars in King County, and the funding package also included lottery funds, a car rental tax and an admissions tax at the ballpark.

The King County Council approved the package on Oct. 23, less than a week after the ALCS ended.

“If we had just had a mediocre season and not a magical season,” says Armstrong, who retired in 2014, “there wouldn’t be baseball here.”

T-Mobile Park, as the retractable-roof stadium born out of that vote is now known, opened in 1999 and will host next year’s All-Star Game. It previously hosted the Midsummer Classic in 2001.

In the building that day in ‘01? None other than MLB director of special events Carolyn Taylor, in her only visit to Seattle.

Taylor left MLB in 2005, after 20 years with the league. Today, she works for her local school district. But she’s kept in touch with Armstrong, comparing notes on Purdue sports. And of course, she still has the watch Armstrong sent her in ’95 as a thank you for her efforts. When she pulled that watch out of storage for her sister’s visit, it brought back fond memories.

[INTERESTING SIDE STORY 2 OF 2: Taylor’s sister has her own brush with baseball fame. She was in attendance for Game 6 of the 2003 NL Championship Series at Wrigley Field, where she sat in extremely close proximity to Steve Bartman. In the famous photo of Bartman impeding Cubs outfielder Moises Alou’s catch attempt, (you can see Laurie Holmes in her white coat below). A coworker she attended the game with snatched up the loose ball and wound up auctioning it off for more than $100,000 to a representative of Harry Caray’s Restaurant Group, which publicly detonated the ball the following February.]

“I wore it way back when,” Taylor says of her 1995 AL West champs watch. “I had a Fitbit watch for a few years and most recently an Apple Watch, so I stopped wearing real watches. But I knew my Mariners watch was a keeper.”

The Mariners, who are finally bound for the postseason for the first time since 2001, proved to be a keeper, too. Maybe baseball in Seattle would have been saved even if the club didn’t win the West in ’95. Or maybe, with Johnson on the mound, the Mariners would have won the tiebreaker even if they had to play Game 163 in Anaheim instead of the Kingdome.

But because we have no way of knowing -- and because it’s WAY more fun to tell the story this way -- Carolyn Taylor deserves a special place in Seattle sports lore. A mere watch might not be enough to recognize her coin-toss contribution.

Then again, it is an appropriate gift for the woman who helped keep the Mariners ticking.