When the Braves became the Bees

There will be a buzz in the building when that day comes that the Braves raise their 2021 World Series banner and receive their rings. But had baseball history worked out a bit differently, we’d be brandishing that “buzz” word not just in description of the exciting scene at Truist Park but in purposely playful homage to the Atlanta ... Bees?

With the Braves on top of the baseball world and with Cleveland having recently become the first Major League team to alter its nickname in over a decade, it’s a good moment to look back at a moniker modification that relatively few people in the present day even know about.

Back when the Braves belonged to Boston, there was a fleeting period in which the “Braves” name was dropped in an unusual -- and ultimately ill-fated -- attempt to rescue a sagging squad.

The Braves' "Miracle" run to a World Series title in 1914 was far off in the rearview mirror, and Boston’s National League team had fallen on tough times, both on the field and in the financials. A drastic and deceitful effort to get butts in the seats by putting a physically deteriorating Babe Ruth in the lineup in 1935 had been a spectacular failure, and the club’s stakeholders had been dissolved by the league after it was determined they didn’t have the money to keep the team afloat.

And so the Boston Braves, under new ownership, tried to change their fate by changing their name.

Here’s the story of the brief, bumbling life of the Boston Bees.

* * * * * * * *

The Red Sox’s decision to sell Babe Ruth to the Yankees in 1920 is among the most bafflingly bad baseball transactions in history. But the Braves’ decision to bring him back to Boston 15 years later wasn’t much better.

Both of those decisions came down to money.

The 1919 Red Sox had stumbled in the standings and at the gate, causing owner Harry Frazee to sell his star for $125,000 in cash and about $300,000 in loans. The 1934 Braves had seen attendance fall by nearly 200,000 fans from the year prior. In the 20 seasons after the “Miracle” run of 1914, the Braves had just five winning seasons, had finished no higher than third place and had finished in sixth, seventh or eighth place 14 times.

So going into 1935, the Braves were in desperate need of a draw.

Owner Emil Fuchs wanted to raise revenue by turning Braves Field into a greyhound dog racing track, going so far as to apply to the Massachusetts Racing Commission for a license. Because ballparks weren’t allowed to serve as gambling facilities, his idea was to have the Braves play their home games at Fenway, as they had done in the 1914 World Series.

Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey responded to the request bluntly: “Over my dead body.” And NL president Ford Frick called the idea “absolutely preposterous.”

Needless to say, the racetrack never made it to the starting gate.

Fuchs couldn’t get his dogs, but he could get the Babe. Ruth had hit .288 with 22 homers in 125 games in 1934 -- decent numbers, but a far fall from the Sultan of Swat’s powerful peak. Ruth would turn 40 just prior to the 1935 season, and it was clear his baseball days were numbered.

The Yankees had no interest in again paying Ruth anything approaching his $35,000 salary from 1934. They offered him a chance to manage for them in the Minor Leagues, but the big fella wanted to remain in the big leagues. So the Braves approached him with an intriguing opportunity. Not only would Ruth have a place in the Braves’ lineup, but he would be adorned with two fancy titles -- “vice president” and “assistant manager,” with Ruth being led to believe he would or could succeed Bill McKechnie as the manager as soon as 1936.

It wasn’t so much a question where the Braves would finish, but if they would finish.

Harold Kaese, sportswriter for the Boston Evening Transcript and Boston Globe

“The obtaining of Ruth undoubtedly will have a wonderful effect on the interest in the National pastime by all lovers of baseball in New England,” James O’Leary wrote in the Boston Globe. “It looks like a masterful stroke of business for the Boston club.”

Uh, not so much.

The Babe’s titles proved empty, and so did his aged bat. Though he hit a home run in his first game back in Boston, he went an entire month without hitting another. He did come through with one last burst of brilliance -- a three-homer game in Pittsburgh on a fleeting late-May day -- but his body had ballooned (even by his own seismic standards), his knee ached, and his batting average was a lowly .181 through 28 games.

Having realized not only the limits of his powers on the field but the insincerity of Fuchs’ promises, Ruth retired in early June.

* * * * * * * *

With the Ruth gambit having fallen flat, the Braves went on to their worst season yet in 1935. They went 38-115 for a .248 winning percentage that stands as the second-worst of the Modern Era. And they drew just 232,754 fans, or about 70,000 fewer than the already woeful ’34 campaign. (The Braves’ attendance was less than half that of the crosstown Red Sox, who drew 558,568 to Fenway that season.)

“About this time in their history, more attention was being paid to Braves owners than to Braves players,” wrote Harold Kaese, who covered the team for the Boston Evening Transcript and then the Boston Globe. “It wasn’t so much a question where the Braves would finish, but if they would finish.”

Charles F. Adams, who replaced Fuchs as team president during that 1935 season, looked for a new owner to take over the team, but nothing came of it. Adams gathered the club’s stakeholders to try to arrange a financial reorganization of the club, but the group could not raise the $350,000 needed to put it on sound footing.

And so, in November 1935, the NL assumed control of the Boston ballclub. Frick, the NL president, called it a “friendly forfeiture.” Though Adams remained the majority stakeholder, the league appointed Bob Quinn, then the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, to assume control of the nearly bankrupt team.

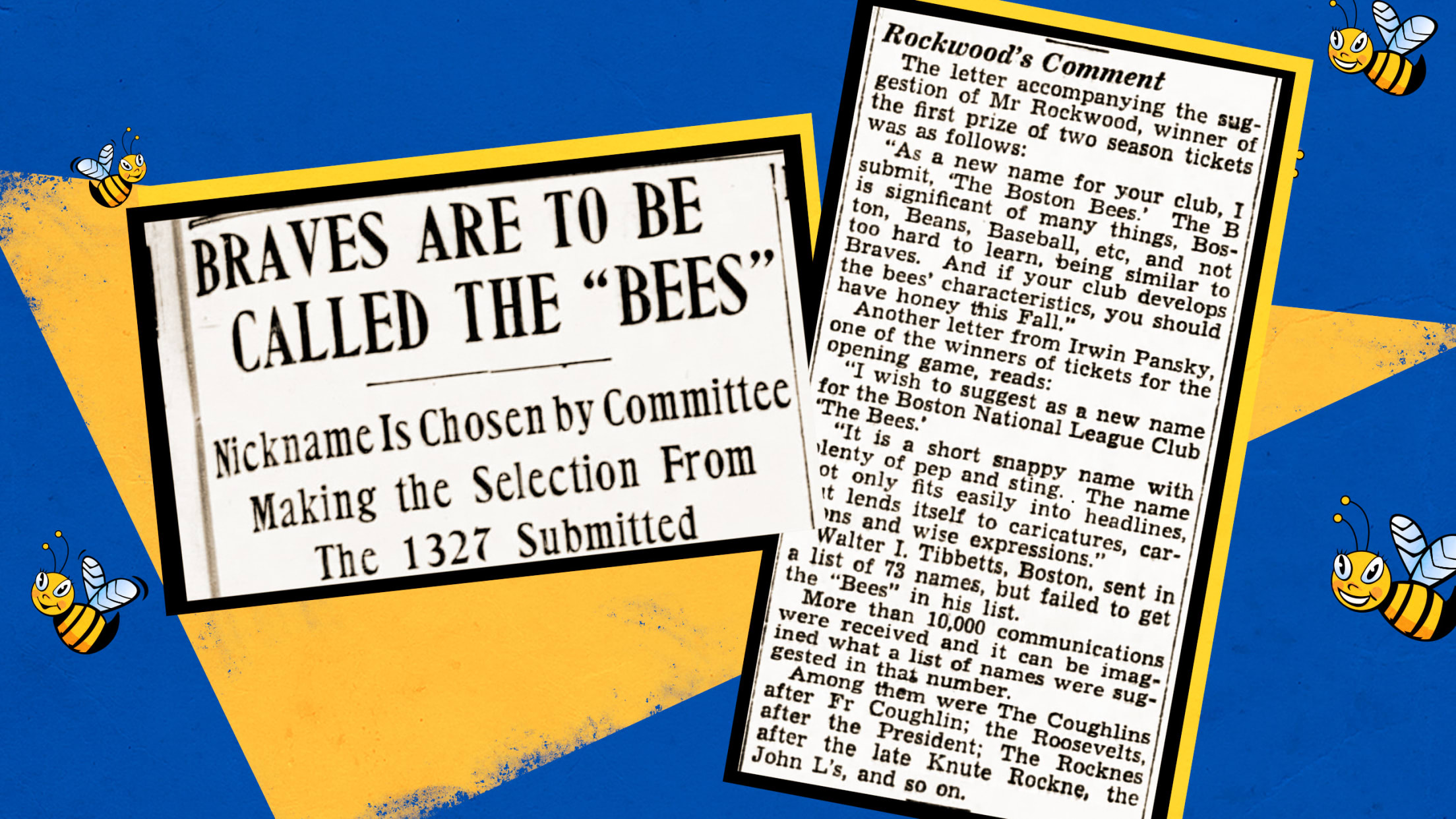

Quinn was not shy about reshaping the squad. Though he retained McKechnie as manager, little else about the club stayed the same. That winter, Quinn made eight trades involving 15 players. And to further distance the team from the disaster that was the 1935 season, Quinn announced in January 1936 that a fan contest would be held to select a new nickname for the team, with two season passes dangled for whoever submitted the winning entry.

The ‘B’ is significant of many things, Boston, beans, baseball, etc., and not too hard to learn, being similar to ‘Braves.’ And if your club develops the bees’ characteristics, you should have honey this Fall.

Arthur J. Rockwood, credited with the name

Major League Baseball’s early years are littered with instances in which teams altered or amended their appellations. Boston’s NL team contributed to that chaos. First, they were the Red Stockings (1876-82), then the Beaneaters (1883-1906), then the Doves (1907-10), then the Rustlers (1911), before finally landing on the Braves in 1912.

By 1936, though, the nicknames of MLB’s 16 teams were seemingly set. The most recent change had come in 1932, when the Brooklyn team reverted back to the Dodgers (the name it held in 1911-12) after 19 seasons of being known as the Robins, in honor of manager Wilbert Robinson. But other than the Dodgers, who made that edit because of Robinson’s retirement, none of the other team names had changed since at least 1915.

Quinn’s proposal, therefore, can be seen as a bit of a bold one, especially with the team having won a World Series under the Braves name. But the desire to divorce the club from the awfulness of the Fuchs era was strong, and so was the initial reaction to the idea. More than 1,300 fans took part in the name-change challenge.

Though entries such as Blue Birds, Colonials and Blues were given consideration, a swarm of Bees -- 15 entries in all -- had been submitted and won over the powers that be. The representative winner of the season passes was Arthur J. Rockwood of East Weymouth, Mass., who had written: “The ‘B’ is significant of many things, Boston, beans, baseball, etc., and not too hard to learn, being similar to ‘Braves.’ And if your club develops the bees’ characteristics, you should have honey this Fall.”

Sweet.

* * * * * * * *

Quinn and Co. hoped that the new name would make for some snappy newspaper headlines.

Quickly, though, the new name was met with a buzzkill.

In the Evening Transcript, Kaese wrote: “As Shakespeare might have said, ‘What’s in a name? That which we call a skunk cabbage by another name would smell as foul.’”

Weirdly, the Bees seemed to swat away their own name from its very inception. Though the team’s colors were changed – from navy and red to royal blue and gold -- the word “Bees” was not included anywhere on the uniforms. The caps and the home jerseys featured only a gold “B,” and the road jerseys had “Boston” stitched across the chest. Braves Field was blandly rechristened not as “Bees Field” but as “National League Field” (sportswriters tried in vain to have it informally called the “Beehive”).

And in what can only be described as a missed opportunity, the team did not draw up a kitschy logo that demonstrated its insect identity.

So the Bees were doomed from the “bee”ginning.

Though attendance did improve by 107,831 fans in that 1936 season, that still put Boston’s NL entry near the bottom of the pack in MLB and well behind the popular Red Sox. Even the 1936 All-Star Game held at the Beehive wasn’t much of a draw. Due to a newspaper error that incorrectly reported that the game was sold out, many fans didn’t even try to obtain tickets, and the result was what still stands as the least-attended All-Star Game ever (25,534).

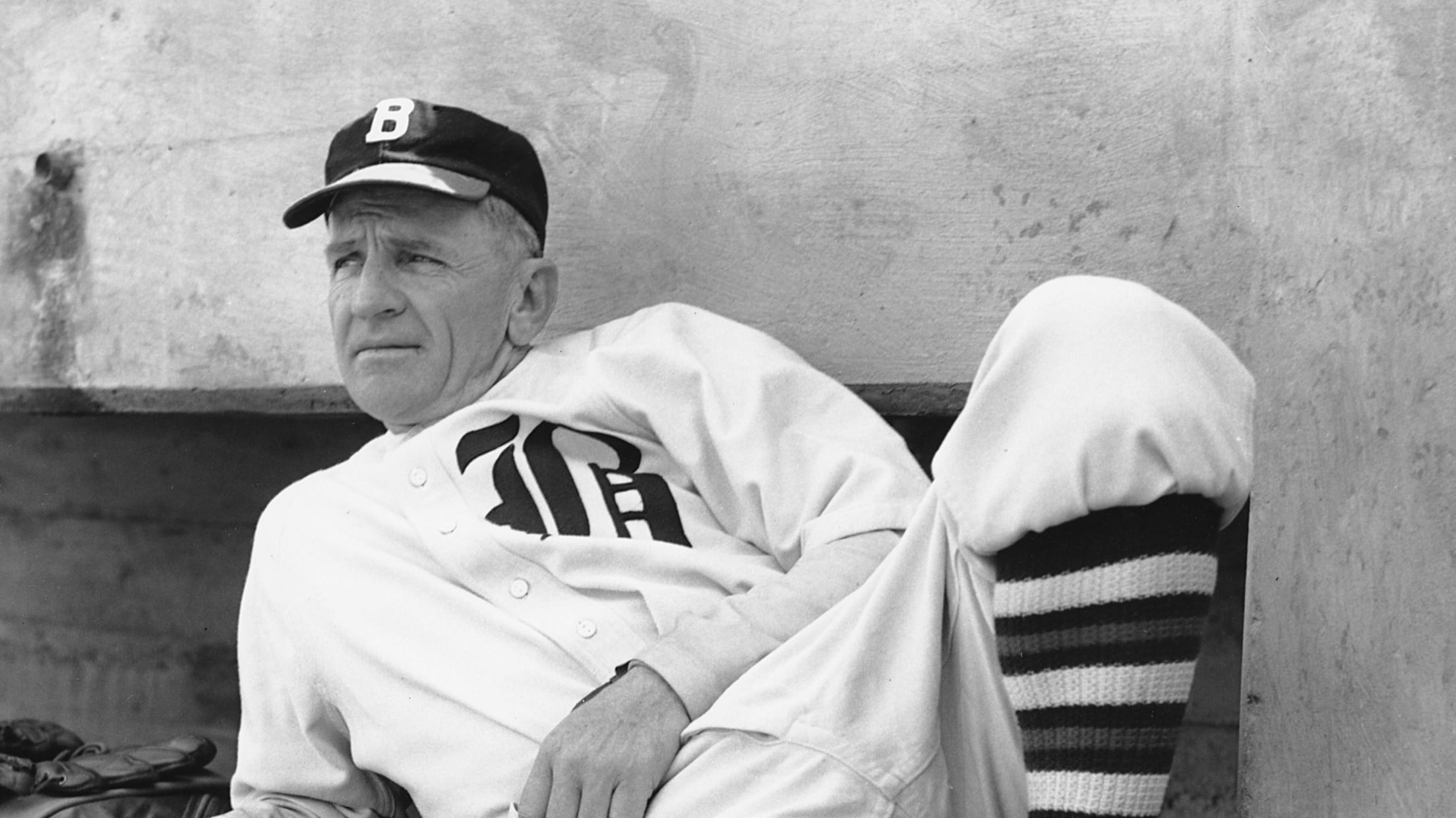

On the field, the Bees did improve upon the Braves’ putrid precedent. The Bees went 71-83 in their inaugural year, nearly doubling the Braves’ win total from a year before. In 1937, they finished above .500 with a 79-73 record.

Still, the Bees’ future prospects were dim enough that their own skipper abandoned them. When McKechnie’s contract ran out after that ’37 season, he left for the Reds, with whom he’d win two NL pennants and a World Series.

Quinn considered a handful of potential replacements for McKechnie, including Ruth (who never did get a managerial opportunity but did briefly serve as a first-base coach for the Dodgers). Ultimately, Quinn offered the job and a small ownership stake to Casey Stengel, who had served as Dodgers skipper under Quinn. Though Stengel had pondered a permanent departure from baseball to concentrate on his lucrative oil investments, he took the job.

The hope was that Stengel’s showmanship would appeal to fans.

“I know he’s got a reputation for being a clown,” Quinn said at the time, “but actually he’s one of the most serious-minded baseball men I’ve ever had work for me. He’s a hustler from the word go, is not afraid to try things with his ballclub, and above all is unflinchingly loyal.”

Though Stengel would go on to become a Hall of Fame manager, it wasn’t because of his work with the Bees. They won 77 games in his first season at the helm in 1938 (when rookie outfielder Vince DiMaggio, brother of Joe, led the team with 14 homers), and that would turn out to be by far the best of his six seasons in Boston.

(Early in what would turn out to be his final season in Boston, in 1943, Stengel was struck by a car in Kenmore Square, shattering bones in his right leg and forcing him to miss a couple months. Boston Daily Record columnist Dave Egan had little sympathy for the skipper, suggesting that the motorist who struck Stengel ought to be honored as “the man who has done the most for Boston baseball in 1943.”)

Only three seasons into the Bees’ existence, a ballclub that hadn’t really embraced its new identity began to turn away from it completely. Beginning with the 1939 season, the royal blue and gold unis were replaced by the navy and red of the Braves. And the reversion in color scheme was accompanied by a reversion in the standings. The Bees finished in seventh place in 1939 and again in 1940.

Not exactly the bee’s knees.

Early in 1941, Quinn headed a group (including Stengel) that purchased Adams’ majority stock in the Bees. At the first meeting of the new owners, a vote was held to officially change the team name back to Braves for that season.

The only catch? The 1941 season had already started. The vote was held on April 29, two weeks after Opening Day. But because of the aforementioned lack of Bee branding on the uniforms, it was relatively easy to make the switch on the fly. As such, in any baseball encyclopedia, the 1941 Boston NL club is referenced as the Braves, not the Bees.

* * * * * * * *

So the Bees had no keeper.

The change back to Braves was the last non-relocation-motivated nickname alteration in MLB for quite a while. The Phillies went by Blue Jays in 1944-45, but that was merely a secondary nickname and a (failed) publicity stunt. The Cincinnati Reds spent five seasons in the 1950s as the Redlegs to disassociate themselves from communism. In 1965, the Houston Colt .45s became the Astros as part of their move to the Astrodome and to resolve merchandise revenue issues with the Colt Firearms Company. In 2008, the Tampa Bay Rays dropped the “Devil” to take on a sunnier disposition. And this offseason, Cleveland made the formal change from Indians to Guardians out of respect to concerns about the use of Indigenous names and symbols.

Braves to Bees and back again is rather unusual in modern baseball history, because the motivation was not political or topical. Boston’s NL franchise basically just wanted to stir the honey pot, then ultimately let tradition take over again.

All these years later, it’s pretty clear that the franchise had problems that ran much deeper than any nickname or even any particular owner. The club finished seventh in 1941 and again in ’42, then sixth in each of the next three seasons. Efforts to build the fan base weren’t helped when, in 1946, the fresh green paint on the wooden seats in the grandstand hadn’t dried by Opening Day, staining the business suits and dresses of the men and women in attendance. (More than 13,000 people sent the team their cleaning invoices.)

Though the Braves, then under the ownership of Lou Perini, did finally experience on-field success by winning the 1948 NL pennant behind the great pitching of Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain, Boston’s two-team identity proved untenable. The annual MVP-worthy efforts of Ted Williams had only aided the popularity of the Red Sox, and Braves attendance once again sagged in the four mediocre seasons that followed that ’48 flurry.

On March 13, 1953, Perini announced that he was seeking permission from the NL to move the Braves to Milwaukee, where the club’s top farm club was located. Within a week, the relocation was made official. Eventually, the site of Braves Field was sold to Boston University and reconstructed as Nickerson Field. The would-be Beehive has been taken over by Terriers.

Had the Boston Braves remained the Boston Bees, would the name have survived the move to Milwaukee and then Atlanta? Would Hank Aaron have been known not just as a home run king but as the King Bee? Would 2021’s World Series champs have worn royal blue-and-gold jerseys and hats adorned with some kind of beloved bee logo?

We’ll never know the answers to those questions, because the Bees were never given the freedom to spread their wings.

And if you’re a lover of silly, simple, pun-ready sports team nicknames, well, that kind of stings.