The Braves are up two games to none over the favored Dodgers in the National League Championship Series, which would be an impressive feat under any circumstances, but might be considered even more so today, considering just how many stars have not contributed to either Atlanta victory. Brian Snitker's team has made it here, up 2-0, without Ronald Acuña Jr. and Mike Soroka, each injured. The Braves have done it without Jorge Soler, on the COVID injured list. They’ve done it without Marcell Ozuna, long suspended. They’ve done it without Charlie Morton, expected to start Game 3 on Tuesday.

They’ve done it, too, without Freddie Freeman, the defending National League Most Valuable Player, although not because he’s been unavailable. Freeman has stepped to the plate eight times and made eight outs, including seven strikeouts in a row to begin the series. He is one of the very few players in baseball history to start a postseason series with seven consecutive whiffs, and one of the others, Jerry Reuss, was a pitcher.

When Game 3 starts, it will have been a full week since Freeman's last hit, which came back on Oct. 12 when he homered off Milwaukee’s Josh Hader. Not that the Dodgers aren’t without missing stars of their own -- Clayton Kershaw, Max Muncy and Dustin May would surely like to be here -- but they haven’t overcome key absences to win the first two games. Atlanta has.

That Freeman has struggled so badly is both a credit to the Dodgers' pitching -- six Los Angeles arms are responsible for those eight outs -- and a reminder of how magnified playoff games can be, because we surely would not be even discussing this if Freeman had struck out seven straight times in a nondescript run of midseason games … which he did in July 2016.

Sometimes, these things just happen, even to the best of hitters. Sometimes, there’s more to it. Here’s how the Dodgers have neutralized Atlanta’s best hitter -- the same man who went 35 consecutive plate appearances without a strikeout back in June -- and what to watch for as the series progresses. Let’s break it down into two approaches.

1. The “righties throwing gas inside” strategy

Four of Freeman's eight plate appearances have come against righties -- Max Scherzer twice, and Corey Knebel and Blake Treinen once apiece. Each of them throws hard, with fastballs averaging in the mid-to-upper 90s, and combined, they’ve thrown Freeman 21 pitches.

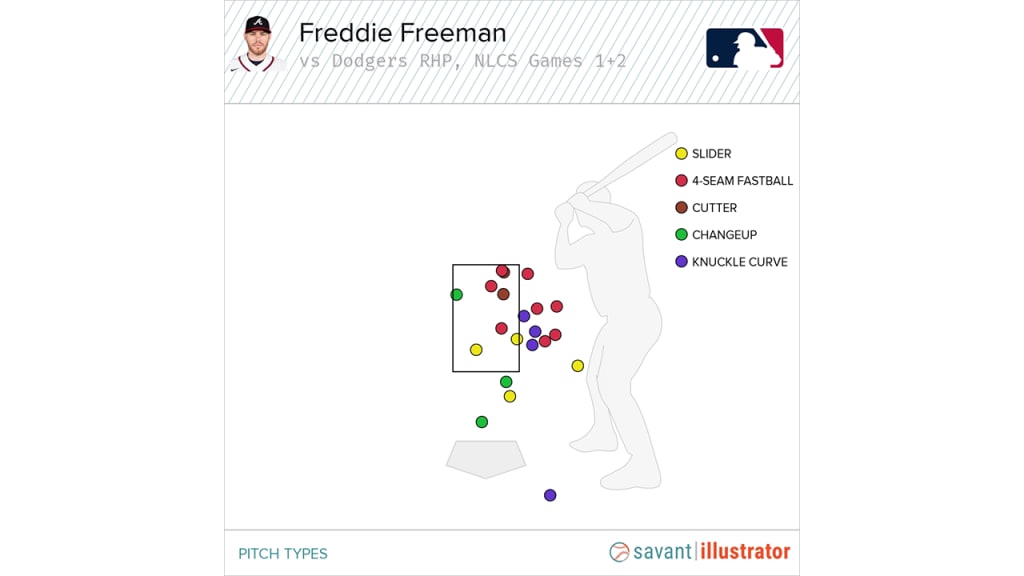

Look, now, where those 21 pitches have been thrown. Aside from Knebel’s three curveballs (purple), Freeman has faced overwhelmingly hard stuff on the inner third of the plate or further inside than that, and occasionally a slider or changeup away or low. All four of the strikeouts, the final pitches of the plate appearance, have been low or inside.

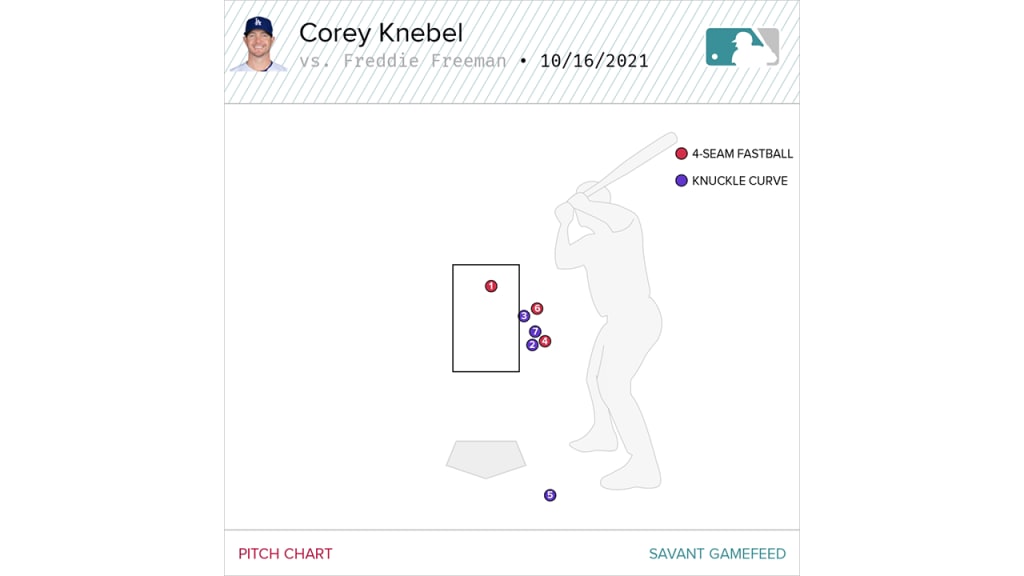

Knebel, in particular, took that approach to an extreme in his lone appearance against Freeman as the opener in Game 1.

Now: “Bust a good lefty inside and get him to chase breaking or offspeed stuff low and away” is hardly a novel strategy that hasn’t already existed for a century or more of baseball. This isn’t suddenly some incredible new game-changing idea that was just invented two weeks ago. And yet: the Dodgers are taking it to a degree so extreme that it’s difficult to think it’s not based on an intentional plan.

Over the years, looking just at right-handed pitchers, Freeman has seen 30% to 40% of his pitches on the inner third of the plate or inside-high/inside-low. (The zones marked 3/6/9/12/14, from the batter’s point of view, if you’re really interested.) It was 39.6% of his pitches in 2021, one of the higher rates in baseball for lefty hitters. In the NLDS, Milwaukee actually didn't take this approach as much; when he faced a righty pitcher, only 28% of pitches came into this inside area. Still, you get the general context here, that against righties, Freeman usually sees inside pitches approximately one-third of the time.

In the first two games of the NLCS, the right-handed Dodgers have done this 81% of the time.

We are, to be completely fair, talking about all of 21 pitches, 17 of which came inside. But as we said above, small samples get obscenely magnified during the postseason. To really see what this looks like, just take a look at how often the 19 teams Freeman faced in the regular season went into those inside zones against him, with the Brewers (NLDS) and Dodgers (NLCS) included as well.

That’s a little about the pitchers the Dodgers had on the mound -- you certainly wouldn’t ask every single righty to do this, as though every pitcher’s repertoire lends itself to it -- and a lot about where they think he won’t be able to do damage.

Of course, in the regular season, he did plenty of damage there. When Freeman had pitches in those zones from righties, he did quite well, hitting .301 with a .582 slugging percentage, striking out 20% of the time. What’s different now? This, again, may not be anything more serious than “a poorly timed cold streak against some high-quality pitching,” so let’s not act with certainty that it is.

But there’s also a thought that the strikeouts, while welcome, are not necessarily the strategy the Dodgers have in mind. For years, Freeman has famously talked about his approach of trying to “send a line drive over the shortstop's head,” and in the second half, likely in an attempt to get away from some of the loud outs that had found shifted gloves early on, he did indeed raise his opposite-field rate from 21% to 30%.

It is extremely difficult to take a pitch, especially one with velocity, in on your hands, and drive it to the opposite field with any sense of authority. On pitches from righties in those inside zones, Freeman had all of seven hits all season long, and nothing more than a single since May. Only one of those was a ground ball.

Not coincidentally, the Dodgers have shifted him 21 times in those 21 pitches he’s seen from their righties … or 100%. They are perfectly happy to let him try to twist himself in knots trying to take those inside pitches to the opposite field, or to fail to make contact while doing so, or to pull it into their shift.

It’s worth noting here, as well, that Freeman has had difficulty simply laying off these sometimes-balls from righties. He’s offered at 63% of them against the Dodgers, after doing so at 59% of them against Milwaukee, after going after just under half (49%) in the regular season.

For all his extraordinary achievements, Freeman has never acted like a traditional lefty slugger, trying to pull the ball to right field. (“I’m still trying to hit the line drive up the middle,” he told The Athletic in June. “I can’t come off of [his approach], because if I try and start pulling the ball I’ll be hitting .180.”)

Game 3 starter Walker Buehler, for what it’s worth, is also a right-hander who throws hard (average of 95.3 mph on his four-seam fastball). Buehler did not use the inside strategy quite this way when they met three times on Aug. 31 … except that on each of the three pitches Freeman grounded out on, they were low and inside. On Tuesday, this is easily the first thing to watch.

2. The “effective lefties you don’t know enough about” strategy

Freeman didn’t only get busted inside by hard-throwing righties, however. He also faced Dodgers lefties four times, striking out in the first three. OK, fine, you know Julio Urías, one of the better lefty starters in baseball, who got Freeman to fly out to left field in Game 2 on a first-pitch curveball, which counts as something of a win for Freeman since it wasn’t a strikeout, even though the pitch was out of the zone.

But do you know rookie lefty Alex Vesia? Do you know fellow rookie lefty Justin Bruihl? Should you? It’s here where it’s worthwhile to ponder whether the issue is “something wrong with Freeman” or “the pitchers are doing an incredible job,” even though the answer is almost certainly in between.

Vesia allowed 10 runs in 4 1/3 unremarkable innings for Miami last year before the Dodgers targeted him in a February trade for Dylan Floro. It quickly became clear why, because even with the Marlins, his fastball rated as truly elite in terms of the much sought-after “rising” effect teams desire, and the Dodgers helped him add velocity to it; where he was averaging 91.7 with Miami, he was touching 96 in Game 2. Vesia has struck out six of 13 hitters in the playoffs, quickly becoming one of Dave Roberts’ best weapons.

Bruihl, meanwhile, wasn’t even drafted, signing with the Dodgers in 2017 as a free agent, working his way up to the Majors with an extremely unusual left-handed pitching profile -- nearly 90% of his pitches this year have been cutter or slider. Without a weapon to handle righty batters, he’s strictly limited to certain situations, but against lefties, he’s allowed six hits (all singles) in 47 plate appearances.

That’s a tough matchup for any lefty batter. Against Freeman, the lefty trio has thrown 15 pitches (only one, again, from Urías). They’ve looked a little different. This time, it’s Vesia throwing rising fastballs up and sliders down, almost nothing in the middle. It’s Bruihl throwing three pitches from the same spot that move three different ways.

In Game 1, Vesia's strategy was clear: fastballs up (though the first two are too far up to be competitive) interspersed with sliders low, the classic "change the eye level" move. On the fifth pitch, the 95.3 mph four-seamer, you can almost see the "rise" we referenced as Freeman swings right under it.

In Game 2, his strategy was identical -- fastballs high, sliders low -- and when Freeman did manage to make contact, they were fouls to the opposite field. After three straight fastballs, with Freeman probably remembering how he'd gone down in Game 1, Vesia slung a slider to the outside part of the zone, throwing Freeman badly off balance.

Again: It's two games. It's eight plate appearances. It's very clear the Dodgers have had a plan, one they've executed somewhat differently than other teams have -- one you can now keep an eye out for in Game 3 -- and so this cannot be chalked up entirely to "it's a fluke." At the same time, Freeman remains one of baseball's truly elite hitters, and even the best hitters alive manage to strike out a ton over two games.

None of this has prevented the Braves from winning. That's entirely the point, though. You wouldn't think they could keep on winning games if they don't start getting production from their long-time star -- and if anyone should know that a 2-0 NLCS lead over the Dodgers is hardly a guarantee of a series victory, it's the Braves, who blew exactly such a lead one year ago. But if they do, if Freeman does all the things you know he can do, then the Dodgers have another problem to contend with. As though, really, being down 2-0 wasn't problem enough.

Mike Petriello is a stats analyst for MLB.com, focusing on Statcast and Baseball Savant, and is also a contributor to MLB Network.