The Yankees didn’t just acquire one of the most elite relievers in the game on Friday when they traded for Milwaukee’s All-Star closer, Devin Williams. They acquired one of the truly elite pitches, too. They acquired the “Airbender,” an offering so famous in Wisconsin that in 2023, the Brewer became a brewer when “Airbender Ale” became a limited-edition offering at the ballpark.

Now, Williams is joining a Yankees bullpen that once had a pitch in the conversation for history’s greatest single offering: Mariano Rivera’s cutter. Rivera rode that pitch all the way to the Hall of Fame, but it was just “a cutter.” It wasn’t a brand. So, as Williams leaves Milwaukee for a new fanbase in the Bronx, let’s explain what the “Airbender” really is, and why it’s as effective as it is.

So: What … is it?

It’s a changeup. Kind of.

“Changeup, changeup -- it's literally in the name,” Williams told MLB.com’s David Adler in 2023. “It's called a changeup. You can't change up off of a changeup. If that's the only thing you're throwing, you're not changing anything, no matter how good it is."

Of course, traditional changeups work off the fastball, creating a velocity and movement separation, and generally come with lower spin. The changeup is the secondary pitch, not the primary pitch. Not so for Williams, who throws the highest-spin “changeup” on record by more than a tiny bit. Consider this: The average changeup, since 2015, spins at 1,769 RPM. Only a small handful get north of 2,200; only four get even up to 2,400. Williams? 2,752 RPM, hundreds of RPM ahead of second-place Trevor Richards.

That doesn’t make it good or bad; changeups aren’t really supposed to spin this much, which is yet another hint that it’s not really the kind of fader you’re used to, as Williams knows well.

“It’s just an outlier pitch,” he told The Athletic in 2020. “The spin I’m able to create makes it different from every other changeup.”

Exactly, because while spin is fashionable to measure and train for, it also doesn’t really matter by itself; it matters in the sense that how you impart that spin affects how the baseball moves, which matters a lot. You’ll be unsurprised to know that no pitch moves like this one.

Williams, in 2024, got 19.4 inches of horizontal break on his changeup, and yes, that is more than the 17-inch width of home plate. You need context for that, so let’s give it to you. Last year, there were nearly 2,000 different combinations of pitcher+pitch type that were thrown at least 100 times – not just changeups, but any pitch type. Out of all of those, only six combinations had at least 19 inches of break, which is three-tenths of one percent of pitches.

Except … that’s not the whole story. Let’s break those six extremely high-movement breakers into direction.

Breaks towards the pitcher’s glove side (5)

- RHP Greg Weissert, sweeper

- RHP Kevin Kelly, sweeper

- RHP Ethan Roberts, sweeper

- LHP Tom Cosgrove, sweeper

- LHP Danny Young, sweeper

Breaks towards the pitcher’s arm side (1)

- RHP Devin Williams, changeup

This, right here, is the entire game. It’s one thing to throw a huge side-to-side breaking ball; while impressive, it happens. But what makes Williams’s pitch so effective is that he’s doing it to his arm side, not across his body.

The pitch, Williams said in that 2020 piece in The Athletic, was something the pitcher saw as “a backwards slider,” and former teammate Josh Hader called it “a lefty slider coming out of his hand.” They’re onto something there.

You might not know Danny Young, a 30-year-old journeyman lefty, and you might not be terribly impressed by his 4.54 ERA for the Mets, either. But the entire reason he’s in the Majors is because of that sweeping slider, the one that held batters to a stellar .113 AVG / .189 SLG in 2024, and looks like, well, that.

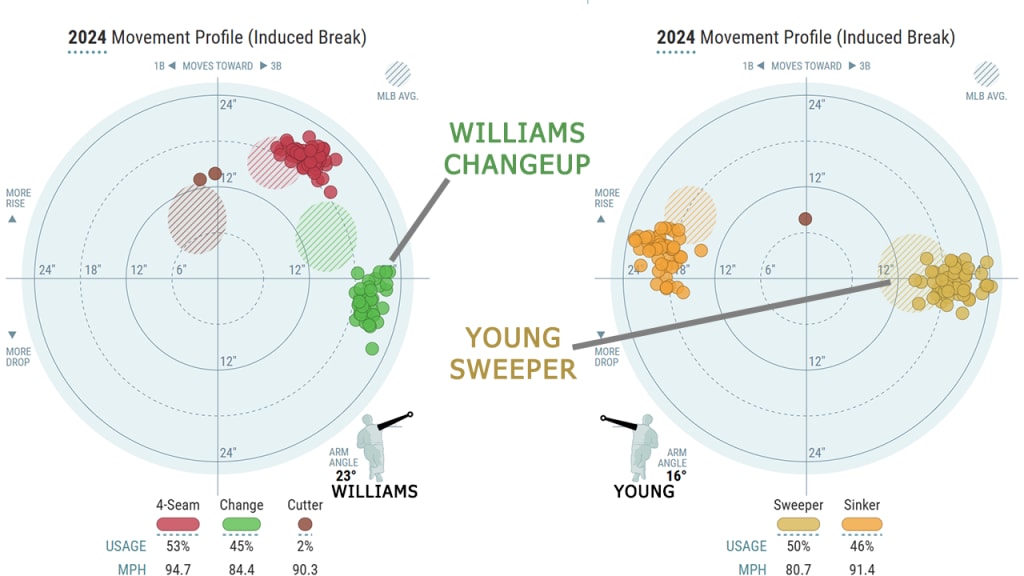

Why do we bring up Young? Because look at how his sweeper and Williams’s changeup move, and how similar they are.

- Young sweeper: 19.6 inches glove side, 43 inches drop

- Williams changeup: 19.4 inches arm side, 42.3 inches drop

Because Williams throws 4 mph harder, the induced movement changes a little differently, just because his pitch has a little less time to drop, making his movement more impressive, but in terms of raw movement, it’s identical.

Remember, a pitch going glove side from a lefty and one going arm side from a righty are moving in the same direction, and that’s really driven home when you look at the respective movement charts from Young and Williams, which show you that, yes, it is something like a lefty slider or sweeper, thrown by a righty.

It’s one thing to throw a slider, for a righty pitcher. It’s another thing to manage to throw a “lefty slider,” and yet another thing for it to have so much movement, to the point that even actual lefty sliders don’t really break as much.

So, what is the Airbender? It’s a pitch that breaks more than almost any pitch, breaks in the “wrong” direction from a righty pitcher, and, lest we forget, drops eight inches more than other righty changeups. Pair that with the ability to throw a fastball that sometimes get up to 97-98 mph, and you’re starting to see what’s happening here.

All of which explains just what Williams is doing, but let’s not bury what it means in terms of the only thing that really matters: “Does it get hitters out?”

The answer is yes, yes it does.

Since arriving in the Majors in 2019, Williams has thrown this thing 2,299 times. He’s collected 546 swings-and-misses; he’s allowed only six regular season homers; he’s allowed a line of .139/.223/.200 against it. Since his 2020 breakout, the pitch has been worth +52 runs, the 10th-most valuable pitch in the game in that time, though remember that the ones ahead of him are from starters, who have had thousands more pitches to collect that value.

On a rate basis (run value per 100 pitches), of anyone who has thrown a pitch type at least 1,000 times in the last five years, Williams’ changeup is tied for the best (+2.4 runs per 100 thrown) with the sliders of Emmanuel Clase and Edwin Díaz, plus the 100 mph bowling ball sinker of Brusdar Graterol.

While the fastball velocity is nice, it's the Airbender that's led Williams to this kind of success -- like the fact that he leads all pitchers in Win Probability Added since 2020, which is a metric we like for closers because, unlike so many other metrics, it does account for context. (That is: A strikeout is a strikeout, but a ninth-inning strikeout with the bases loaded matters a lot more than a fourth-inning bases-empty whiff in a blowout.)

It’s why, then, that Pete Alonso’s crushing home run off Williams in the 2024 NL Wild Card Series was so stunning. Williams had thrown 290 changeups, dating back to Sept. 1, 2023, without allowing a long ball on it. It was just the seventh homer of his career against the pitch, which, again, he's thrown thousands of times.

If using a changeup as a primary pitch sounds a whole lot like Tommy Kahnle, we’d agree. But Williams doesn’t really throw a changeup, or a screwball, or even a slider. He throws an Airbender. It’s the only one there is.