De Jon Watson, the Nationals' director of player development, has traveled out of the country for years to scout potential Major Leaguers. But there’s one baseball trip Watson, 55, will never forget.

As senior vice president of baseball operations for the D-backs in 2015, Watson was taking his first scouting trip to Japan, and he was nervous. It was in Japan that his father, blues legend Johnny “Guitar” Watson, passed away in 1996. Johnny was on stage in Yokohama when he suffered a heart attack. He died hours later in the hospital.

“The first time I went to Japan, I was really nervous. I was going to the 18-U [Baseball World Cup] in Japan,” De Jon remembered. “All I could think about was calling my sister and wife from Japan. I was freaking out. I was a little nervous because I knew he had his heart attack on stage in Japan. It makes you think about it. ‘This is not an omen, is it?’

“My wife said, ‘Go there, do your job. Your father is looking out for you.’ I went to a flower garden and paid my respects. ... I got through it. I’ve been back to Japan a couple of times since then. The first trip was probably the hardest. The second and third time I was there, it was a lot easier for me.”

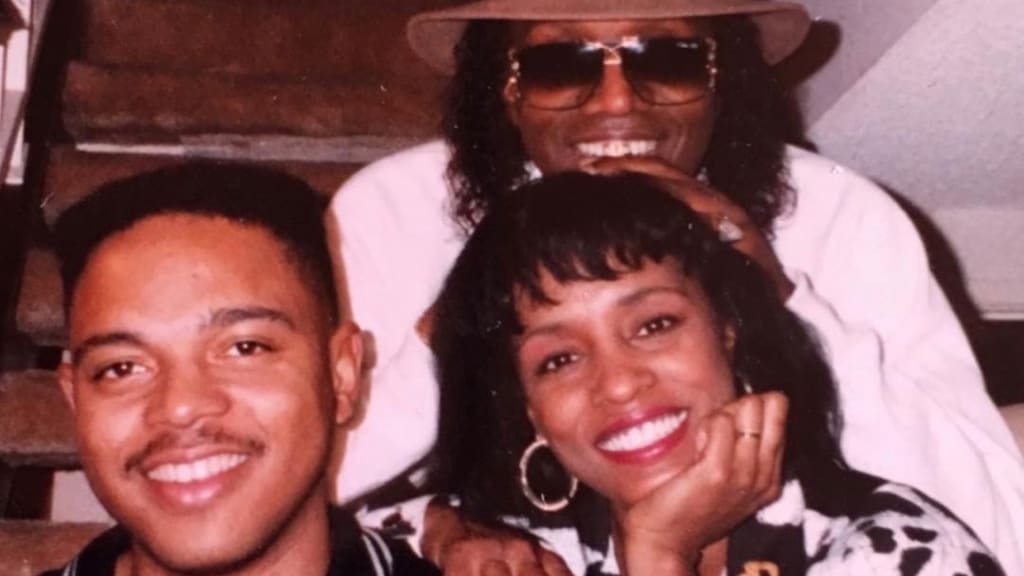

Watson's father was not into baseball, but he was among the best blues musicians. In a career that spanned 40 years, Johnny was a consummate showman on stage and influenced musicians such as Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan. Johnny could give jazz singers a run for their money with his scatting, and in the 1970s, he wowed with funk albums.

He reached his peak in 1977 with such hits as “Tarzan” and “A Real Mother For Ya.” His songs such as “Superman Lover” and “Loving You” have been sampled by current entertainers such as D’Angelo and Jay-Z, respectively. Johnny was also known for his shades and stylish wardrobe.

Johnny lived long enough to see De Jon play Minor League Baseball in the Royals’ organization and begin his scouting career with the Marlins.

“He caught me in Baseball City when I was with the Royals,” De Jon said. “He came out for a week. He was wearing his shades at night. My dad was the coolest guy that I knew growing up. He wore shades at night while driving. Having him with me while I was chasing my dream, he was really supportive of what I was doing.”

De Jon learned a lot from his father and admired his father’s perseverance and business acumen. As a kid, De Jon listened to his father negotiate record deals with music executives such as Al Bell and Herb Alpert. Sometimes, those negotiations got heated. Johnny wanted to be fairly compensated for his work and effort. He wrote 740 songs, according to De Jon, and he owned the rights to all of them.

“I watched how hard he had to work to gain his recognition in the industry. He wasn’t mainstream,” De Jon said. “His skill set was so unique. He could do R&B. He could do jazz. He could do blues. He could [do] funk. He was so well rounded that the [music critics] had a hard time putting him in a category. It took the industry a bit longer to figure out who he was and how his music played.

“As a young guy in the car, we were talking about business. I was like, ‘Can you buy me McDonald’s?’ He would say, ‘Get out of here about buying McDonald’s.’ He is going to educate me on his business. It was really cool.”

De Jon didn’t follow in his father’s footsteps, even though he grew up surrounded by musicians.

“He never pushed me one way or the other. When I was taking my piano lessons, he would sit down and work with me,” De Jon said.

While growing up in Los Angeles, his next door neighbor was Barry White. Frank Zappa and Etta James were close family friends, while Marvin Gaye, Ray Charles and Lou Rawls often came by the house to talk shop. Even more amazing: Natalie Cole bought De Jon his first electric guitar. He was 12 years old at the time.

“She came by one evening. We were having dinner when she came by and brought the gift,” De Jon said.

Baseball wasn’t too far behind. He grew up with Don Buford Jr., Damon Buford and Daryl Buford, who are the sons of Orioles legend Don Buford. Current D-backs manager Torey Lovullo and his family lived around the corner from the Watson family.

“It was a part of life,” De Jon proudly said.

Though he was surrounded by musical legends, De Jon dreamed of playing baseball or football, and Johnny always encouraged his son to follow his passion. Toward the end of his life, Johnny started to understand the game of baseball. A few days before he died, Johnny watched on TV as Al Leiter pitched a no-hitter for the Marlins, a team De Jon was working for as an area scout. Johnny then called his son from Japan.

“He called me and said, ‘How about that Al Leiter dude?'” De Jon recalled. “He was really starting to get into the game. He was really supportive, and he loved listening to me talk shop and talk about baseball with him.”

De Jon is now in charge of the Nationals’ Minor League system. If Johnny were alive, he would be extremely proud of his son.

“He would be rockin’ it and watching the Nationals,” De Jon said. “He would look forward to watching some games with us.”

Bill Ladson has been a reporter for MLB.com since 2002. He covered the Nationals/Expos from 2002-2016.