It’s a story that sounds like “The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of.”

When Jackie Robinson and his family were between homes -- stymied in their search because of the racist real estate practices of the early 1950s -- they were taken in by a white Connecticut couple that helped them secure a plot of land. Like the Robinsons, the couple had young children, one of whom was a 10-year-old girl who would tag along with Jackie to Dodgers games and serve as the team’s unofficial mascot. And, like Jackie, she would go on to compile a lot of hits … only hers were of the music variety.

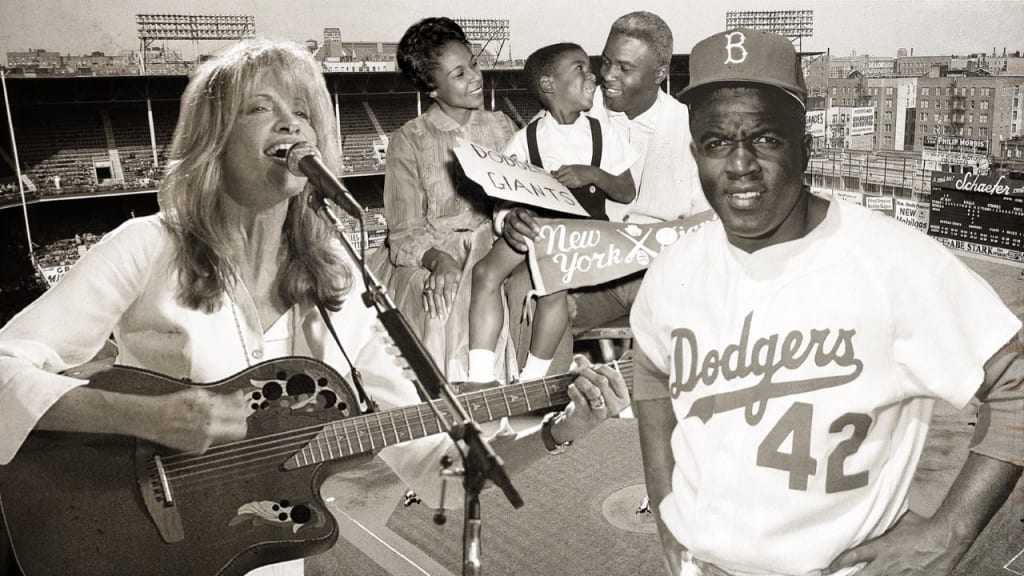

Carly Simon’s relationship with the Robinsons is a fun footnote in both Jackie’s story and her own. Not many know these two Hall of Famers -- Robinson in Cooperstown, Simon in both the Rock and Roll and the Songwriters Halls of Fame -- crossed paths, let alone that they had an almost familial friendship.

But it’s all true.

“I was very proud of Jackie,” Simon wrote in “Boys in the Trees,” her 2015 memoir, “and my knowing him was a very big deal.”

Jackie was a very big deal in the early 1950s, having not only integrated MLB but established himself as an MVP and a perennial All-Star for the Dodgers.

Alas, just because he had changed the sport didn’t mean he had changed the country. Just because he was a star on the diamond didn't mean he had overcome the biases, prejudices and inequities a person with his skin color faced in the wider world.

When Jackie’s wife, Rachel, gave birth to the couple’s third child, David, in 1952, they had begun to outgrow their Tudor home in the St. Albans neighborhood of Queens. The cramped quarters and the persistence of fans flocking to their front lawn to snap photos made the Robinsons long for a more spacious abode away from the hustle and bustle.

The search, however, proved difficult and demoralizing.

The Robinsons centered in on one home in Purchase, N.Y., north of New York City, but the home was not-so-mysteriously pulled from the market when the Robinsons offered the asking price. The owners of a home for sale in Greenwich, Conn., refused to even show them the property. And when they toured a house in Port Chester, N.Y., white neighbors of the home glared at them.

Clearly, Jackie’s status with the Dodgers afforded him no escape from this quiet form of segregation, which Rachel would later say was even more destructive than anything they faced in the south.

“The attitudes and the practices in the south were easier to try to understand or to fight against than the subtle racism in the north, where people said, ‘Oh no, we’re not racist,'" Rachel once said. “It just happens that all bus drivers are white.”

What distinguished Jackie in his day was not just his powerful play on the field but his powerful voice off it. As he became established as a bona fide big leaguer, he became outspoken on civil rights matters, and Rachel joined him. So when a reporter from the Bridgeport Herald asked to interview Rachel for a story on racist housing practices, she obliged, and the Robinsons’ difficulty in securing a home became the focal point of the piece.

Stamford, Conn., resident Richard Simon, the founder of the publishing house Simon and Schuster, and his wife, Andrea, read that piece. And so, an unexpected friendship was set into motion.

“My mother read somewhere that Stamford was still acting like a segregated community, unlike many of the towns around Stamford,” Carly recalled in a 2011 interview with NPR. “Stamford was a strange kind of a holdout for some sort of bigotry that they didn’t even own up to. And she was horrified by this, and she got in touch with Rachel Robinson somehow, and she said, ‘Meet me on the Merritt Parkway.’”

The scenic Merritt Parkway runs through Connecticut’s Gold Coast, including Stamford. Andrea Simon, a community activist, offered to take Rachel on a tour of houses and land available in the area.

“The long and the short of it,” Carly continued, “is that they became very, very close friends. My parents went around to the politicians and the religious leaders of the community in Stamford and basically integrated the community by breaking the color barrier with having the Robinsons buy the first plot of land in Stamford, Conn., that was to be owned by an African American.”

That plot of land was at 103 Cascade Road in Stamford. With the help of the Simons and a pair of local bankers, the Spelke brothers, the Robinsons purchased the land from contractor Ben Gunnar, who they hired to construct their dream home. The house, however, would not be ready in time for the 1954 school year. The Simons offered the Robinsons a place to stay so that Rachel could oversee the building project.

The Simons, the Robinsons and their combined seven children would wind up together for about 18 months.

The late Peter Simon, Carly’s younger brother, reminisced to the Vineyard Gazette in 1997 about that special time in his childhood.

“Jackie spent so much time teaching us about baseball,” Peter said. “We’d stand out in the backyard, and he’d hit us grounders with a tennis racquet and a tennis ball. He used to whale the ball and hit these towering high flies. We were so into it, especially Carly, who was a true-blue Dodger fan.”

In her memoirs, Carly recalled going to Dodgers home games at Ebbets Field, sitting on Pee Wee Reese’s lap in the dugout and serving as the team’s informal mascot. The team had a special jacket made for her, with “Dodgers” printed on the back and “Carly” on the front.

“Jackie even taught me to bat lefty, though it never took,” she wrote. “I loved him. He always had the cutest look around the side of his mouth, as if he were thinking about what he was about to say before he said it.”

Whenever the Dodgers were on television and Jackie would step to the plate, Andrea would kiss the screen to give him good luck.

This welcoming, loving reception from the Simons stood in stark contrast to the coolness the Robinsons received from the broader community. Jackie was denied membership at a Connecticut country club, and his children were often made to feel isolated at school. No matter how famous or important Jackie Robinson might have been, he and his loved ones were never not reminded of the color of their skin.

That’s what made the relationship with the Simons so special. And long after the Robinsons moved into their own home, long after the children grew and went on to their own lives and careers, long after both Richard and Jackie passed away, the bond between Andrea and Rachel persisted.

They remained close until Andrea’s death in 1994, at the age of 84.

“Andrea and I had more than a friendship,” Rachel once told the Vineyard Gazette. “We were like sisters.”

Carly told NPR that Rachel was by her mother’s side when she was dying.

“[Rachel] spun a very, very significant, beautiful web around our family,” Carly said. “And she also empowered [Jackie] and also kidded him out of being ultra-serious, which he sometimes could be, or ultra-defiant, which was sometimes for a good purpose and other times not. Rachel was always there just to show [Jackie] where the ground was, not what a ground-rule double was necessarily.”

Just as Jackie Robinson was a central figure of the Civil Rights movement, Carly Simon was an important figure in the feminist-birthing 1970s, recording classics like “You’re So Vain” and “Anticipation.”

But she never forgot her relationship with Robinson and the fandom that experience instilled in her. In Ken Burns’ famous “Baseball” documentary, you’ll find Jackie in the film and Carly on the soundtrack, with her rendition of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.”

The story of how these two Hall of Famers in their respective crafts came together demonstrates another dimension to the difficulty Robinson and his family faced after he broke the color barrier and the help of the friends they found along the way.

Anthony Castrovince has been a reporter for MLB.com since 2004.