Marcus Semien is one of the most desirable free agents available, yet also one of the most difficult cases to evaluate. In his first four seasons as Oakland's shortstop, Semien was just OK, consistently being an average-to-slightly-below hitter along with being a below-average defender. In 2019, he finally broke out, mashing 33 homers to go with a .285/.369/.522 line and improved fielding, earning him a third-place finish in AL MVP voting. It seemed like it might be the beginning of something great.

Unfortunately, that all came crashing back to earth in 2020, when Semien hit only .223/.305/.374. His defense got worse. So 2019 was a fluke, right? Maybe. But maybe not. Maybe it's because we know he wasn't fully healthy, or because he collected only 236 plate appearances in a shortened season, a number he reached on May 24 in 2019. Was he considered a star on May 24, 2019, when he was hitting .268/.363/.410 with five homers? Probably not.

***

So, what do you do with that? How on earth do you evaluate performance over one-third of a season when trying to project forward? In some cases, it's easy. Mike Trout had been great for years, and he was great in 2020. Same for Jacob deGrom or Anthony Rendon or George Springer. You don't need to change your impressions of those players.

Yet others had unexpectedly good or poor seasons, and it's important to try to figure out if those are entirely because of small sample streaks or based on something more. So let's look at the 10 hitters who improved the most from 2019 to 2020 and the 10 who declined the most and see if we can determine how "real" those things might be.

We'll look only at batters who had at least 350 plate appearances in 2019 and 130 in 2020, in part because it gives us similar numbers of players (244 batters hit that mark in 2019, and 241 did in 2020). We'll use FanGraphs' Weighted Runs Created Plus, or wRC+, where "100" is league average, and Trout's 164 mark last season can be read as "64% better than average."

First, we'll look at the 10 hitters who improved the most from 2019 to '20, and let them state their cases. We'll follow up soon with those who took the biggest steps back.

TEN WHO GOT BETTER

José Iglesias, Orioles

+76 points, from 84 wRC+ to 160 wRC+

Iglesias had spent nearly a decade being the archetype of the light-hitting smooth-fielding shortstop; in nearly 3,000 plate appearances entering 2020, his career line had been .273/.315/.371 (83 wRC+). So when a guy like that hits .373/.400/.556 in a shortened version of a shortened season -- he played in only 39 games due to several injuries -- it's very easy to write it off as an unrepeatable fluke. (Especially since he walked just three times all year, and had a .407 batting average on balls in play, literally the highest in Baltimore history for players with as many plate appearances as he had.)

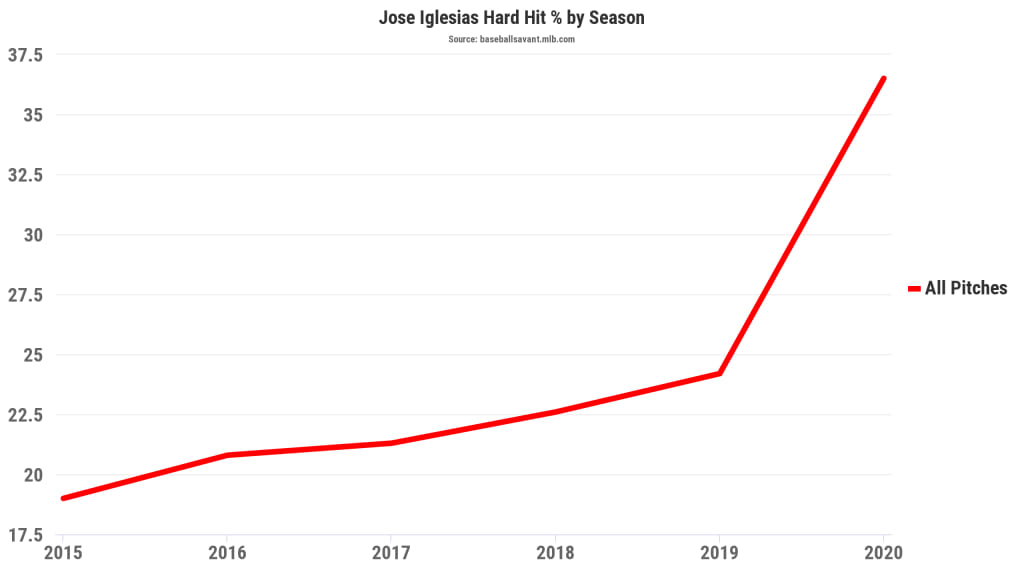

That's probably true, and we'll take the hard under on a repeat in 2021, because we're not going to let 150 plate appearances matter more than nearly 3,000. But we'll at least point out this, which is that while Iglesias managed to maintain his elite contact rate -- his 11.3% strikeout rate is in the top 2% of the league -- he managed to increase a routinely poor hard-hit rate to nearly league average.

That probably also doesn't meaningfully change our view of Iglesias. It at least helps us think his 2020 was not all "luck," though.

Verdict: Probably a fluke, but at least somewhat interesting.

Brandon Belt, Giants

+74 points, from 99 wRC+ to 173 wRC+

Belt had spent years being one of the game's more underappreciated hitters, as the shift and his spacious home park kept his batting average and home run totals low, and who thinks of a first baseman who has not once hit even 20 homers in a season as having enough bat for the position? Park-adjusted stats always told a different tale -- he was a top-10 hitter among regular first basemen from 2013-19 -- although his semi-regular injury issues held him back as well.

Then in 2020, Belt posted a stunning .309/.425/.591 line that was well above anything he'd ever done before. It's important to note that the Giants had changed the dimensions of Oracle Park before 2020 to make it more hitter friendly, and that the entire team seemed to have benefited both from that as well as considerable benefits from a new coaching staff. (Though just before the season began, Belt said he "didn't really notice a difference" in the park.) It's possible that the park-adjusted metrics, like wRC+, haven't yet caught up, and are giving him too much credit without knowing the park is fairer.

Still, Belt did cut his chase rate and doubled his barrel rate, which saw the third-largest increase in baseball. Those things aren't likely ballpark specific.

Verdict: Not this real, but pretty real.

Marcell Ozuna, Braves (free agent)

+70 points, from 109 wRC+ to 179 wRC+

Ozuna's first year in St. Louis was pretty disappointing, and we wrote that he'd underperformed in elite hitting metrics. Ozuna's second year in St. Louis was also pretty disappointing, and so we wrote again that he'd underperformed in elite hitting metrics. (As we said after 2019: "This past year, his 49.2% hard-hit rate was in the 96th percentile, top dozen in baseball, as hard as Christian Yelich or Yordan Alvarez. Over his two years in St. Louis, he's been one of the 25 best hitters in the game based on Statcast's quality-of-contact metrics.")

So of course, Ozuna mashed in 2020, posting a .338/.431/.636 line. Just a case of overcoming bad luck, right? Not exactly. It was clear his shoulder wasn't healthy for much of his time in St. Louis, and his already-strong hard-hit rate went up in 2020. The average distance on his fly balls and liners, for example, went from 290 feet in 2018-19 to 305 in 2020, and his ground-ball rate, which had been nearly 50% in 2015, was down to 37%. He probably slightly over-performed after two years of under-performing, but he got better, too.

Verdict: Like Belt, not this real, but pretty real.

Jeimer Candelario, Tigers

+65 points, from 72 wRC+ to 137 wRC+

The first 1,110 or so plate appearances of Candelario's Tigers career, from 2017-19, hadn't exactly been that exciting. He'd hit .227/.321/.381 with a 91 wRC+, and he was sent back to Triple-A Toledo twice in 2019. It didn't seem like 2020 would be much better when he started off 0-for-his-first-17, but then he went on a tear, hitting .327/.396/.554 after Aug. 1, which was good enough to get himself voted "Tiger of the Year."

The underlying metrics mostly supported it, especially the fact that, like Iglesias, he showed a pretty monumental uptick in his hard-hit rate.

But we didn't put too much into that for Iglesias, so why would we for Candelario? Partially because he's young -- he played last season at just 26 years old -- and because even before the season began, he talked about the changes he'd made in his approach and swing. "I can recognize pitches better now. I’m more explosive and I have more time to decide what I want to do with the baseball," he said in February. "It’s huge, man.”

We're not fully in yet, but any time a young hitter can increase a hard-hit rate like that without raising his strikeout rate, we're at least intrigued.

Verdict: Cautiously optimistic.

Juan Soto, Nationals

+58 points, from 142 wRC+ to 200 wRC+

We wrote back in 2019 that Soto was off to the kind of career start that all but guarantees you entrance into the Hall of Fame someday, and that was before he went and posted an obscene .351/.490/.695 line in 47 games after having his 2020 season delayed due to COVID-19. He cut his strikeout rate, improved his walk rate and hit the ball hard more often. He's currently one of the five best hitters through age 21 of all time. We're willing to believe almost anything at this point.

Verdict: Soto is probably not this good, but he's already an all-time hitter. Real.

José Ramírez, Indians

+58 points, from 104 wRC+ to 163 wRC+

This one's easy, for once, because we can do better than think about his 2019 as being that of a "104 wRC+," or league-average, player. Think about him this way:

2017: 146 wRC+

2018: 146 wRC+

2019, first half: 68 wRC+

2019, second half: 176 wRC+

2020: 163 wRC+

What happened? Starting late in 2018 and extending into the middle of 2019, Ramírez was in a dreadful slump. We're oversimplifying the reasons and the dates a little here, but for the sake of brevity, it seems that it was largely about his efforts to beat the shift. That is, he tried to go to the opposite field, getting away from his power, and it made him considerably worse. This isn't just a theory, because his agent tweeted exactly this in June 2019. Soon after, he stopped trying and started mashing.

Just look at this chart comparing his pull rate (blue) with his OPS (red). It's not hard to see a connection.

It's a little more complicated than this, but maybe not much more. Don't beat the shift, kids. It's how the shift beats you.

Verdict: The rebound began in 2019, not 2020. Real.

Wil Myers, Padres

+58 points, from 96 wRC+ to 154 wRC+

No National Leaguer cut their strikeout rate by as much as Myers did from 2019 to '20, and that's generally been his issue more than anything, because he regularly hits the ball hard. Myers, when asked, didn't have much to attribute the change to other than some allusions to a "consistent approach," which makes it hard for us to really pin a reason on his '20 success.

But for what it's worth, Myers did end 2019 with a red-hot September (.312/.365/.532), so if you were to look at every hitter with 200 plate appearances dating back to last Sept. 1, he's 13th best, just ahead of Luke Voit and Corey Seager. If you're saying that's an arbitrary sample size, well it certainly is, though no more than a 60-game season is. Plus, it's worth noting that just before that, in early July 2019, FanGraphs' Ben Clemens wrote that while Myers was striking out too much and having a relatively poor season, "there are no two ways about it; Wil Myers is hitting baseballs as hard as he ever has."

It's all a bit amorphous, since there's no return to health or change of scenery (he's been in San Diego since 2015) or obvious swing change, aside, perhaps, from a back-foot pivot change, to point to. But it feels like there's something here, too, in part because of his relative youth (only 30 in December), his track record of being mildly above average, and the fact that the entire Padres offense made some clear changes in 2020. (Not only did San Diego's hitters cut their chase rate from 2019 more than any other team, they did it by nearly twice as much as the second-place Blue Jays. They also improved their hard-hit rate more than anyone aside from the Dodgers. It wasn't all Myers.)

Maybe the Padres kept him while trading away almost every other outfielder they've had for the past few years because no one would take his contract. Maybe they saw something they liked, too.

Verdict: Without a great deal of confidence, this one feels like it's got something to it.

Miguel Rojas, Marlins

+52 points, from 90 wRC+ to 142 wRC+

Take the Iglesias example above, but remove the interesting hard-hit improvement. Like Iglesias, Rojas has long been a light-hitting infielder (.263/.314/.348 with a 81 wRC+ in nearly 2,000 plate appearances entering 2020), and like Iglesias, Rojas missed about one-third of a season that was already one-third as long. (Like several other Marlins, he missed several weeks in August due to a COVID-19 outbreak.) It's nice that he doubled his walk rate, but the underlying metrics don't show much else to hang your hat on.

Verdict: Stone-cold fluke.

José Abreu

+50 points, from 117 wRC+ to 167 wRC+

After a fantastic 2014 debut, when he was the unanimous winner of the AL Rookie of the Year Award, Abreu spent the next five seasons being solidly above average, which mostly means that he was never bad, rarely elite, always good. As he entered his age-33 season, you figured you'd get more of the same, and the White Sox would be happy enough to have it. Instead, Abreu went off, posting a .317/.370/.617 (167 wRC+) line that was as good as his 2014, and enough to earn him the 2020 AL Most Valuable Player Award.

Abreu didn't have a terribly meaningful difference in strikeout or walk rates, and while his hard-hit rate did go up a little, he's always rated very well in that department. So what happened? Let's look at this 100-plate appearance rolling chart over the past three seasons of a Statcast metric called Expected wOBA, which basically accounts for the quality of contact (exit velocity, launch angle), as well as the amount of contact (strikeouts, walks).

The peaks of his 2020 aren't meaningfully higher than his best moments of previous years. He clearly never had the slump he did in 2018, and the more "solid average" moments of 2019 never had time to show up. Basically, it seems to us like he had some of his best moments, but nothing wildly out of character with what we've seen him do in the past.

Verdict: Nothing fluky about his 2020 season, but probably not enough to make us think this line is a "new normal" as he turns 34

Freddie Freeman

+49 points, from 138 wRC+ to 187 wRC+

The Freeman story is at least a little similar to Abreu's, in that a long-time star first baseman had something like a career year and took home an MVP Award. Unlike Abreu, Freeman did show improvements in both his walk rate (a career-best 17.2%) and strikeout rate (a career-low 14.1%), while at the same time upping his hard-hit rate from 42.5% to 54.2%. As far as Statcast is concerned, Freeman was the second-best hitter in baseball in 2020, behind only Soto. It's not too soon to discuss his eventual Hall of Fame case.

So no, there was nothing "lucky" or unearned about Freeman's 2020. The larger question is similar again to Abreu's, which is whether it was a two-month hot streak or an ascension to a new level. We're a little more bullish on Freeman than Abreu, partially because he's three years younger, but also because of something he said in January, regarding the troublesome right elbow on which he underwent surgery last winter:

“It’s the first time in nine years I haven’t had any pain in the offseason,” Freeman said. “Usually, I’m taking about four extra-strength Tylenol right now when I’m hitting."

His doctor went even further, at least in Freeman's words.

"[Dr. Altchek] said, 'I don’t know how you played with this.'"

Freeman's underlying expected stats -- the ones that capture exit velocity, launch angle, strikeouts and walks -- match his actual output almost exactly, as well. Nothing fluky here. Let's further the Abreu comparison by taking a look at the same rolling chart.

He hadn't been hot quite like this in either of the two previous seasons, and that trend line was still going up. It'd come down at some point in a six-month season, of course. It would have to. But what if the injury was really a limiting factor even as he excelled before, and a clean bill of health played into his 2020? Well, we'd sure like to see what a full season of that might look like. We imagine Braves fans might, too.

Verdict: Don't expect a full season of what he did in 2020, but it seems reasonable to expect more than he'd done in recent years -- and those years were good. Mostly real.

Mike Petriello is a stats analyst for MLB.com, focusing on Statcast and Baseball Savant, and is also a contributor to MLB Network.