Aaron Judge appears well on his way to a 60-homer season. Assuming he pulls it off, he’s going to be part of one of the most exclusive and elite clubs in baseball history. Babe Ruth did it in 1927. Roger Maris did it in 1961. Then, Barry Bonds, Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa did it six times in a four-season span from 1998-2001. That’s eight times, total. If Judge gets there, and it appears he will, that’ll be nine. That’s it, in all of recorded history. Nine times, by six players.

But there’s something different about this time, isn’t there?

Judge isn’t playing pre-integrated competition like Ruth did. He’s not playing in an expansion year like Maris, McGwire and Sosa were. Plus, the offensive environment today hardly resembles the high-flying -- and controversial, to put it mildly -- turn-of-the-21st-century times that saw home run records regularly shattered.

The baseball world has changed considerably since 2001, or 1961, or 1927. Almost all of it has changed in a way to make hitting more difficult, for any number of reasons, most revolving around velocity, pitch movement, and the endless streams of high-octane arms who don’t worry about pacing themselves to go deep into games. This, above all else, is why the strikeout rate keeps going up; the next time a batter from a half-century ago complains about today’s hitters, remember that their task is immeasurably more difficult than his was.

There’s no such thing as an “easy” 60-homer season, of course. But given that knowledge, and the fact that Judge has 55 right now in a season where no one else has even made it to 40, it made us wonder just how much more challenging it might be for him to do it now than for them to do it then.

Judge probably won’t get to 73. He may or may not top McGwire or Sosa. But no matter what the final tally is, what he’s doing, in some ways, is even more impressive than any of the ones that came before him.

Let’s run down the list why …

1) Because Ruth did not face the best competition available.

If we’re going to do any comparison of Judge to Ruth, we have to start with the most obvious and important issue: Ruth, alone among our five players, played pre-integration baseball. The pitchers he faced were almost exclusively white and American-born, thus many of the most talented players were purposefully excluded. That’s not hard to prove: In the Negro National League in 1927, you could find star pitchers like Bullet Rogan, Bill Foster and Satchel Paige. It’s not necessarily Ruth’s fault that he didn’t face them, but it does not change the fact that he didn’t face them.

In 1927, there were all of five players born outside the United States (including the baseball hotbeds of, uh, England and Austria-Hungary). In 2021, the most recent full season, there were 418. It’s not that Ruth didn’t face any talented pitchers; it’s that we know for a fact many of the pitchers he did face were simply not as good as those he would have or could have had the integration barrier not stood.

Ruth gets to claim that he hit his 60 in only a 154-game season, eight fewer chances than the rest of our group. But we know without question that the talent base today, the level of athlete, is far superior to what it was a century ago, and Ruth wasn’t even facing all of the best of his time. Judge, a biracial athlete who likely would not have been allowed to be on Ruth’s team, has an immeasurably more difficult assignment.

2) Because Judge has had to face many, many more pitchers.

In 1927, Ruth faced 67 pitchers all season. Maris faced 101 in his magical season.

Entering Wednesday’s doubleheader, Judge had faced 224 pitchers. Pitcher 225 was Twins rookie Louie Varland. Judge introduced him to the Majors with home run No. 55.

With series remaining against two teams he’s not seen yet (Milwaukee and Pittsburgh) and the usual September roster shenanigans, Judge might get up to around 240 or so pitchers faced, all with their own arm slots, repertoires and approaches. It will be nearly four times what Ruth saw, and more than twice what Maris saw.

That’s a side effect not only of the way pitchers are used these days as it is that there are simply more teams to see more of, more of the time. In 1927, long before Interleague Play, in an eight-team American League, Ruth faced the same seven teams, over and over and over again. Since those teams barely used relievers, and seemed allergic to the premise of injury replacements -- note that the 1927 Yankees used only 10 pitchers all year long -- Ruth was seeing the same arms all year.

It’s true that Judge gets the benefits of video and modern scouting reports. But with increasing evidence that things like the "third time through the order" penalty are more about familiarity than fatigue, it seems like a big deal that Judge has to deal with many times more pitchers than his Yankees slugging predecessors. Score one not only for Judge, but for the turn-of-the-century trio, who all saw around 200 pitchers apiece annually.

3) Because fewer and fewer of those pitchers are starters …

But it’s not just the number of pitchers, is it? It’s the way those pitchers are used. Back in Ruth’s day, a reliever was seen only in case of injury or disaster; nearly half of American League games that year featured a complete game, and 88% of innings were thrown by starters.

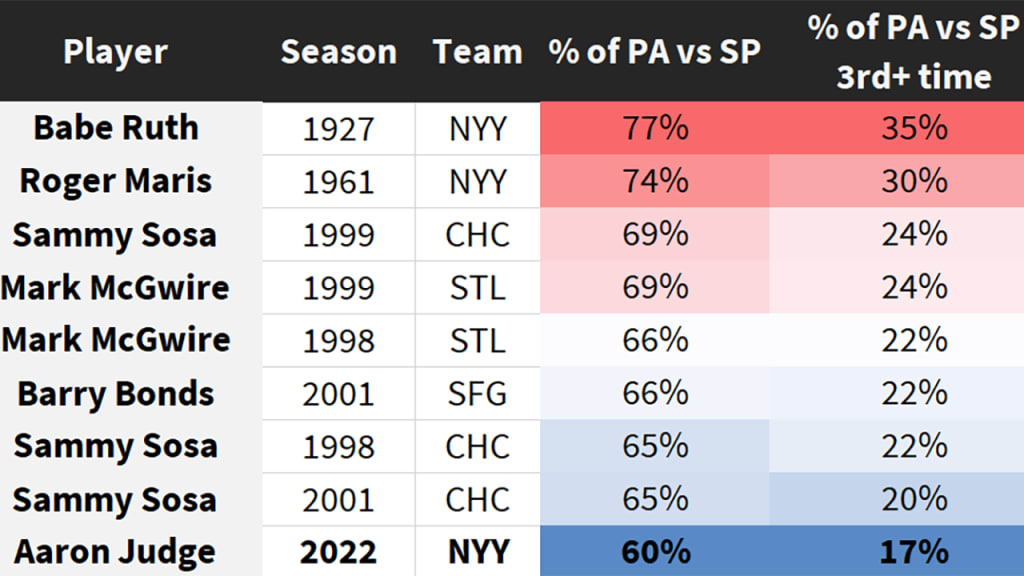

Maris was still decades away from the modern bullpen; 77% of innings came from starters in 1961. It was a little more modern for the Bonds-McGwire-Sosa trio, who saw starters about two-thirds of the time, a number Judge might like to see; he’s at just 60% of his plate appearances coming against starters.

In fact, hold that thought, because just “starters” isn’t good enough. Look at this:

4) … and because those starters aren’t working deeply into games.

This, really, is it. Aside from Ruth’s pre-integration opposition issues, this is the key. It’s one thing to face a starter. It’s another thing to face a starter the third or fourth time through -- a thing Judge rarely gets to enjoy.

While this may be a modern construct, the effect has been around forever, even if people didn’t know it. Thirty years ago, John Smoltz was worse the third time through (by 37 points of OPS) than he was the second, and worse the fourth time through (by 96 more points) than he was the third. Decades before that, Bob Gibson was 50 points worse the third time through. Decades before that, Carl Hubbell was 93 points worse the fourth time through than the first.

It goes without saying that seeing starters deeper into a game is a pleasure for hitters; Hall of Famer Frank Robinson, for example, hit 15 more homers against starters the third time compared to the first despite taking nearly 650 fewer plate appearances against them. It also goes without saying that in 2022, Judge just about never, ever gets to do this.

For his career, he has a .526 slugging percentage against starters the first time he sees them. He has a .664 slugging percentage the third time he sees them, which is why it's so rare an opportunity.

It might be even starker than that table makes it look. In 2021, for example, the entire Majors combined for just 526 plate appearances against a starter the fourth time through the lineup. In 1927, with a shorter schedule, with 14 fewer teams, there were 13,684 such plate appearances. That is, in 31% fewer games, the tactic was used 2,502% more often. Even then, it was detrimental, with an OPS 54 points higher than starters going through the first time.

In 1927, Ruth hit a dozen homers off starters he was seeing for a fourth time that day. Even more recently, Sosa hit five homers off a starter the fourth time through in 1999, and Bonds hit four in 2001. Here in 2022, Judge has taken just two plate appearances off a starter the fourth time through -- and both times, it was Max Scherzer, a living legend at the top of his game.

Ruth also hit nine homers off a reliever he was seeing the second time -- or more -- that day. More than half of his homers, 31, or 53% came off of either starters the third (or more) time through or relievers the second (or more) time. Judge? Only 19%. If he saw starters being used the same way the Babe did, he might be looking at an 80-homer season at this point.

5) Because this is not an especially strong year for power hitting.

We have, mostly, explained why it’s so much harder to hit in 2022 than it was in 1927 or ’61. Let’s focus on the more recent trio, who were playing in some extremely high-flying offensive times. (Three of the seven sluggiest National League seasons ever came between 1999-2001.) So far as a rising tide lifts all boats, it was a good time to be a slugger -- which is how you saw 60 topped six times in four years.

Judge, however, does not have that luxury. The Majors, taken collectively, are slugging just .395 this year, which would be the second-lowest mark of the last 30 years. April’s slugging was so low that it was one of the five lowest-slug months since the 1970s. With a month to go, we’re about 2,300 homers short of 2019’s record-setting total.

It would have been easier to try to set this record in 2019 or 1999 than it is in 2022, is the point. To that end, note that of the eight previous 60-homer seasons, three of them -- all by Sosa -- didn’t even lead the Majors in home runs, which tells you a lot about what baseball was like in those days, to the point that even if Judge doesn’t top Sosa’s years, it certainly feels more impactful to be "first by a whole lot" rather than "second-best that year."

Of the remaining six (including Judge), he has the largest home run gap over second place.

+19 // Judge 55 over Schwarber 36 // 2022

+13 // Ruth 60 over Gehrig 47 // 1927

+9 // Bonds 73 over Sosa 64 // 2001

+7 // Maris 61 over Mantle 54 // 1961

+4 // McGwire 70 over Sosa 66 // 1998

+2 // McGwire 65 over Sosa 63 // 1999

That’s underselling it, really; his gap of +19 home runs is the largest of any season in history outside of a handful of Ruth years, though entertainingly not the 1927 season.

Judge is not going to out-homer the other teams in the AL, as Ruth did in 1927, but his .682 slugging percentage compared to the AL’s .391 is massive. He’s out-slugging the rest of the league by 75%, which is the largest gap since Bonds two decades ago. It's the largest gap in Yankee history since ... well, 1927.

6) Because there is so much more travel required.

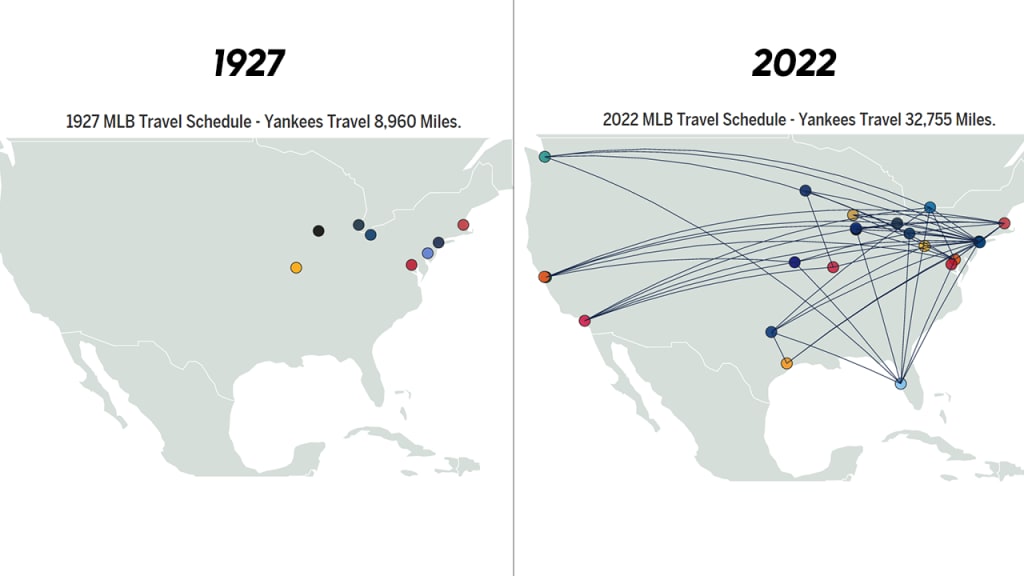

We’ll stipulate here that when Judge travels, he’s doing so in comfortable first-class airline accommodations, a far cry from the trains Ruth rode a century ago. Then again, Ruth often had his own private train car, and he never heard of “jet lag” either, spending all but 22 games in the Eastern Time zone -- and going no farther than St. Louis or Chicago otherwise.

Maris had to at least get to Los Angeles, in the first year of the Angels’ existence, though the trio of three-game sets were the only games the Yankees played out of America’s two more eastern time zones.

Judge, meanwhile, and the rest of the Yankees are traveling 32,755 miles this year, nearly four times as much as the mere 8,960 that Ruth’s 1927 team did.

This doesn't set Judge apart as much from Bonds, Sosa and McGwire, especially Bonds, the only slugger here from a West Coast team. In 2001, his San Francisco team covered 41,042 miles.

7) Because it’s not an expansion year, or near one.

Of the eight previous 60-homer years, three came in expansion seasons. Those were Maris in 1961, when the Angels and reborn Senators joined the AL, and Sosa and McGwire in 1998, when the D-backs and (Devil) Rays joined the Majors. Because Sosa and McGwire also topped 60 in 1999, you could say that 5/8 of the 60-homer seasons happened within two years of expansion, which added dozens of new pitchers, and 7/8 of them -- all but Ruth’s -- came within four seasons of an expansion year.

8) Because the pitching is so much better.

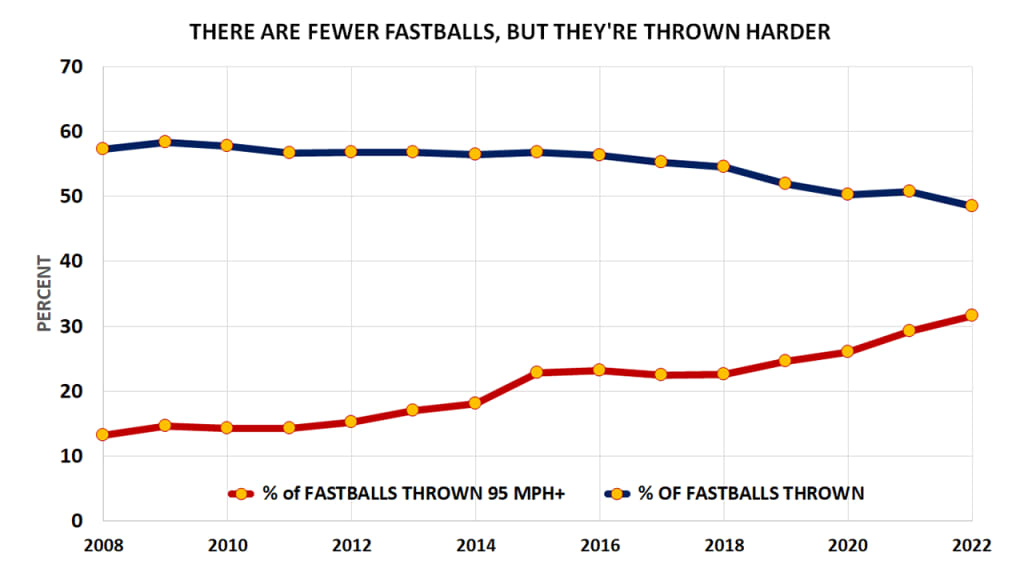

We have to end back on this, even though we can’t really prove it given the lack of reliable pitch data before 2008. There was no Statcast in 2001, much less 1927. We’ll never know how hard Walter Johnson threw, or what Bob Feller’s breaking pitches really did. But based on the 15 years of information we have, we know what the trend has been. Allow us to share a version of a chart you’ve certainly seen before.

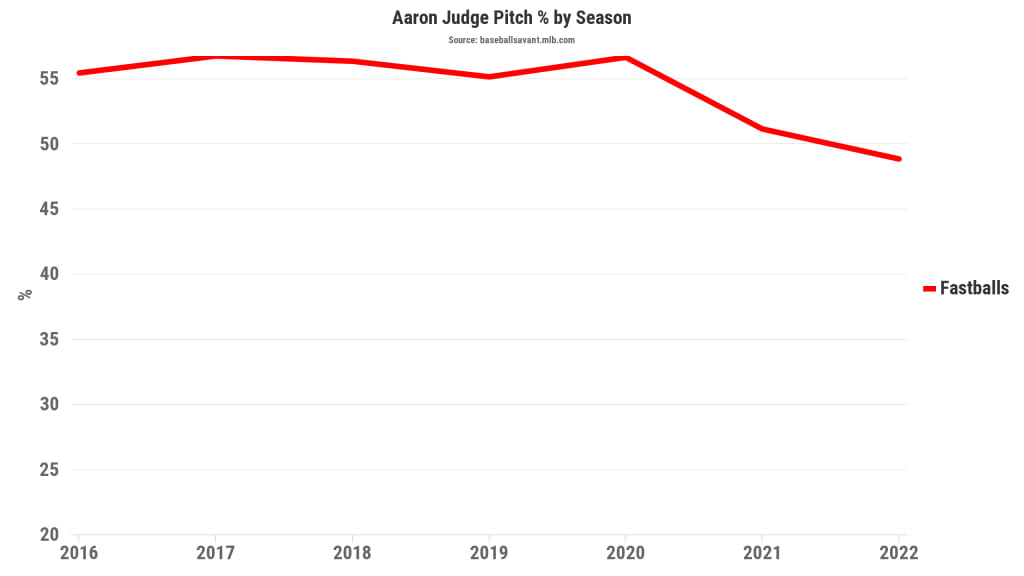

There are no "fastball counts" anymore. We’re hovering around a 50/50 fastball/non-fastball split, which for decades would have been unthinkable. Judge, certainly, would love to see more fastballs; he’s got about two-thirds of his career homers against them, and his career slugging percentage is 200 points higher against them.

Like most everyone else, he’s not seeing them as often. Not that it’s stopped him from mashing what he does get. But just imagine if he saw pitching like Maris did, or Ruth did, or even the turn-of-the-century trio did?

Babe Ruth, a Yankees outfielder, hit 60 homers in 1927. Roger Maris, a Yankees outfielder, hit 61 homers in 1961. Aaron Judge, a Yankees outfielder, has 55 home runs (and counting) in 2022. Those are all facts. But the similarities in pinstripes and home park name are about all those years have in common. What Judge is doing is harder, in so many different ways.