The history of Hinchliffe Stadium through 29 Hall of Famers

For more than two decades, the students of School No. 5 in Paterson, N.J., looked out the windows across Liberty St. and saw the crumbling horseshoe of Hinchliffe Stadium, its white façade covered in graffiti, the artificial turf bubbling and peeling and the six-lane track gradually disintegrating into gravel. Vagrants and vandals trashed the former locker rooms, concession stands and bathrooms. Fires broke out, trees took root in the grandstand, and a sinkhole swallowed part of the field.

What was once a popular destination for barnstorming ballclubs, national entertainment acts and residents of the city had become an eyesore next to one of its crown jewels, the 77-foot cascade of the Great Falls.

Before Hinchliffe reached the brink of demolition, it enjoyed a 65-year run as a venue for baseball, football, track and field, boxing, auto racing and concerts.

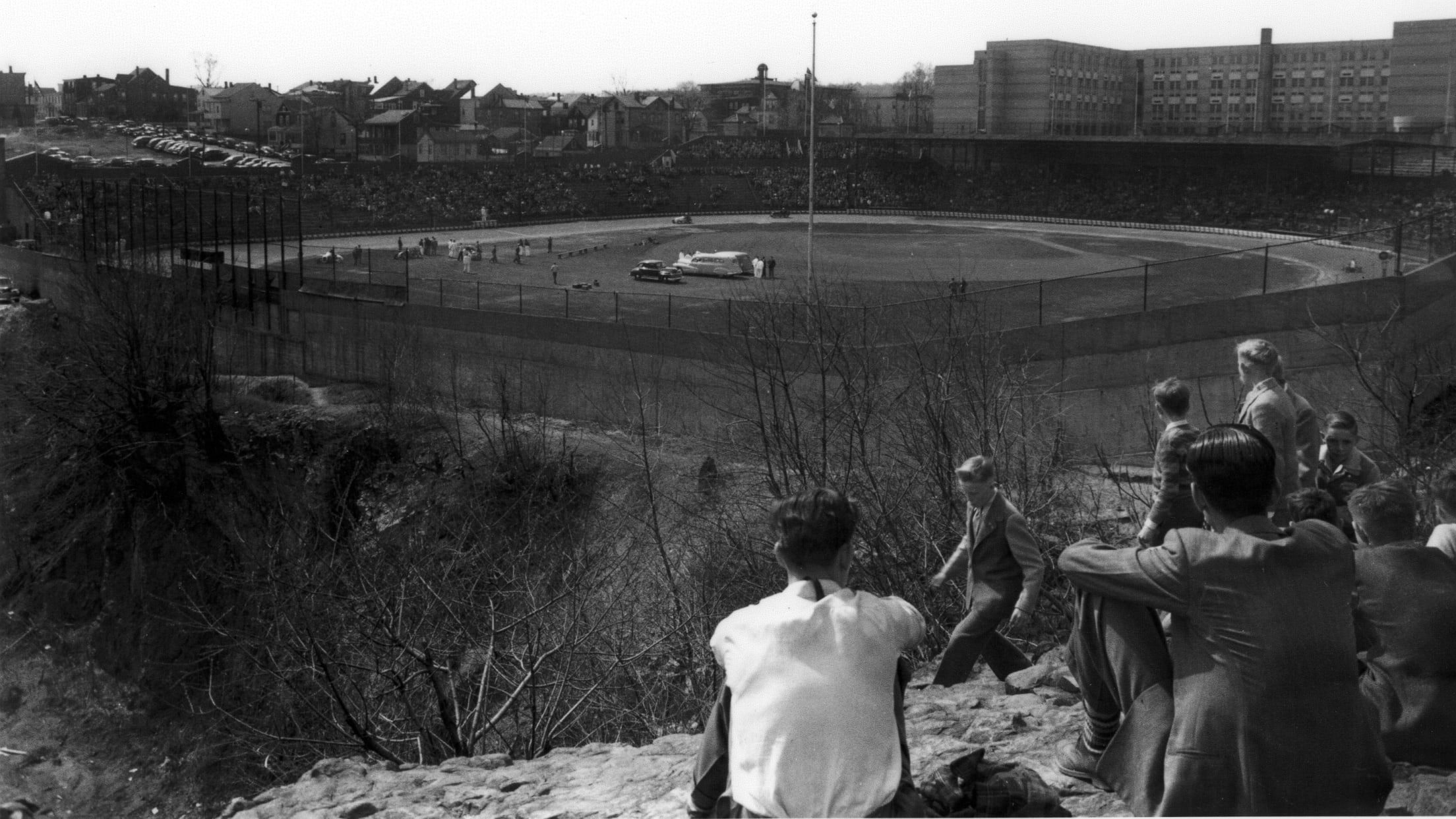

On Friday morning, a ribbon cutting ceremony will rededicate a refurbished stadium, and on Saturday, the New Jersey Jackals of the Frontier League will play the first professional ballgame there since a 1950 exhibition between former Major Leaguers and local Minor Leaguers.

The Jackals’ move to the stadium this season from nearby Montclair will make Hinchliffe Stadium the only former Negro Leagues ballpark currently active as the home field of a professional team.

Here is a look back at its long history, with a focus on 29 baseball Hall of Famers – plus a few others – who have performed on its field, track and stage.

A pretty view and a pageant debut

On July 10, 1778, General George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and others stopped for a picnic on their journey from the Battle of Monmouth to New York City during the American Revolution. They sat on a bluff overlooking the Great Falls of the Passaic, which later inspired Hamilton, as Treasury Secretary, to establish the city of Paterson as a manufacturing center.

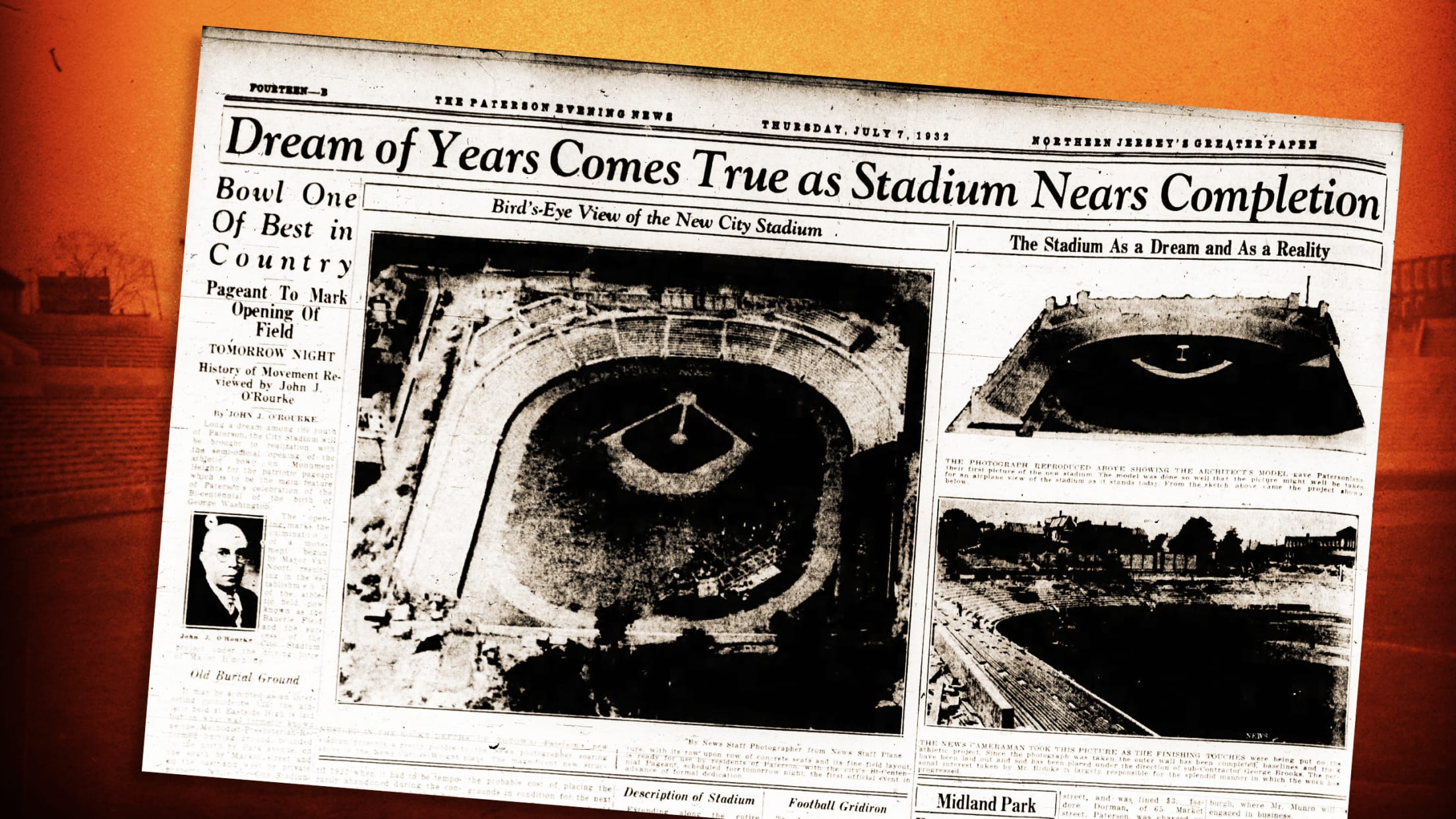

One hundred and fifty-four years later, in 1932, America celebrated the 200th anniversary of Washington’s birth with bicentennial pageants held across the country. Many communities staged their events over the July 4th weekend, but Paterson waited four more days and put on a two-night spectacle that doubled as the grand opening of the new City Stadium.

More than 7,000 spectators turned out each night, according to Paterson’s Morning Call newspaper, to watch 1,500 performers move “forward through nine episodes of intense action, in which the life and career of Washington and the trials, customs and figures of the Revolutionary period were vividly portrayed.”

“Within the concrete walls of the city’s handsome new stadium, high on the rocky bluff overlooking the historic Passaic falls and underneath a cloudless sky, there was unfolded a scene of such magnitude and magnificence as has never before been attempted or seen in this city.”

The official dedication took place on Sept. 17, 1932, when the arena was given the name Hinchliffe City Stadium, honoring the late John Hinchliffe, who was mayor of Paterson from 1897-1903, and his nephew, John V. Hinchliffe, the mayor at the time.

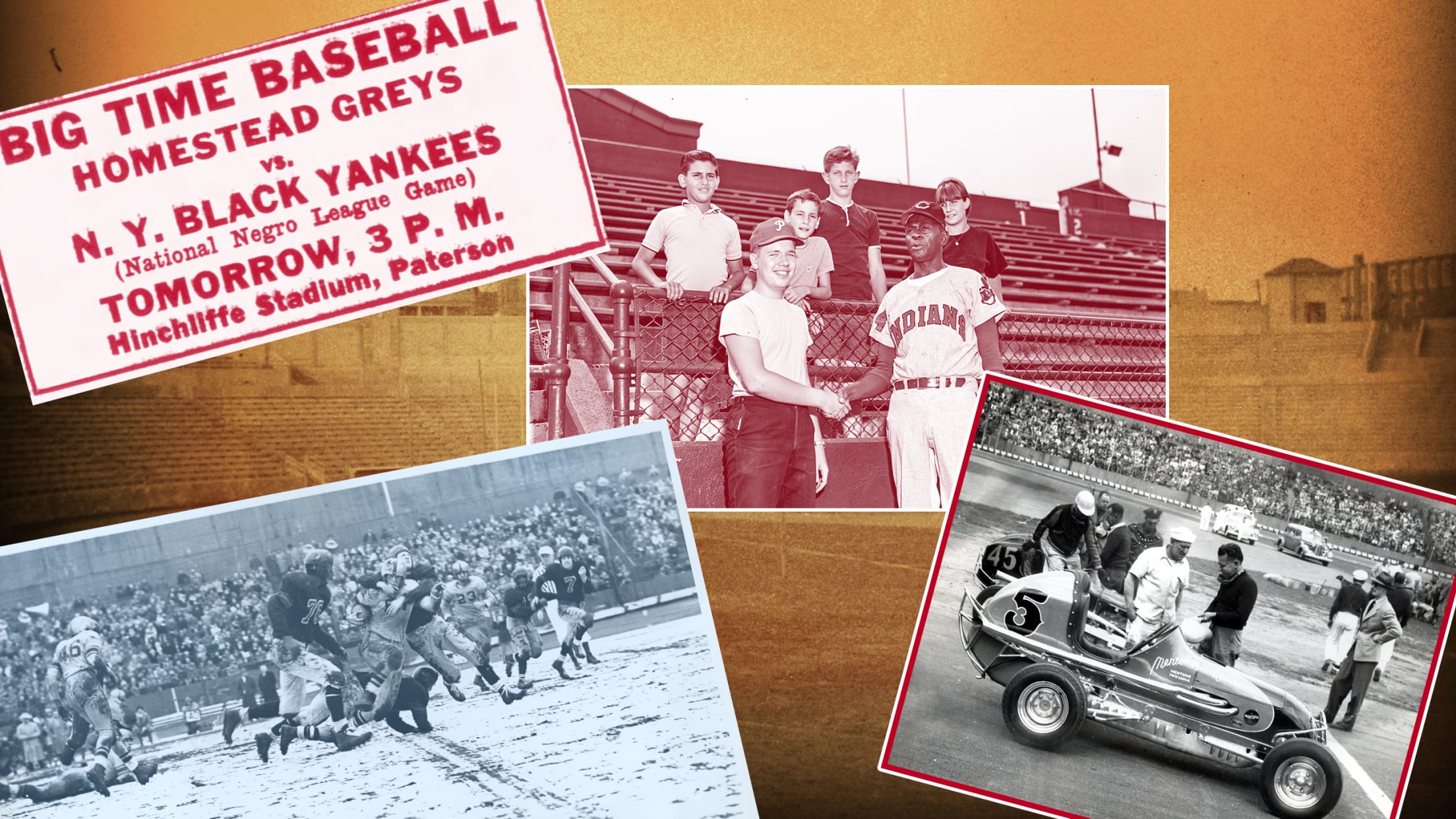

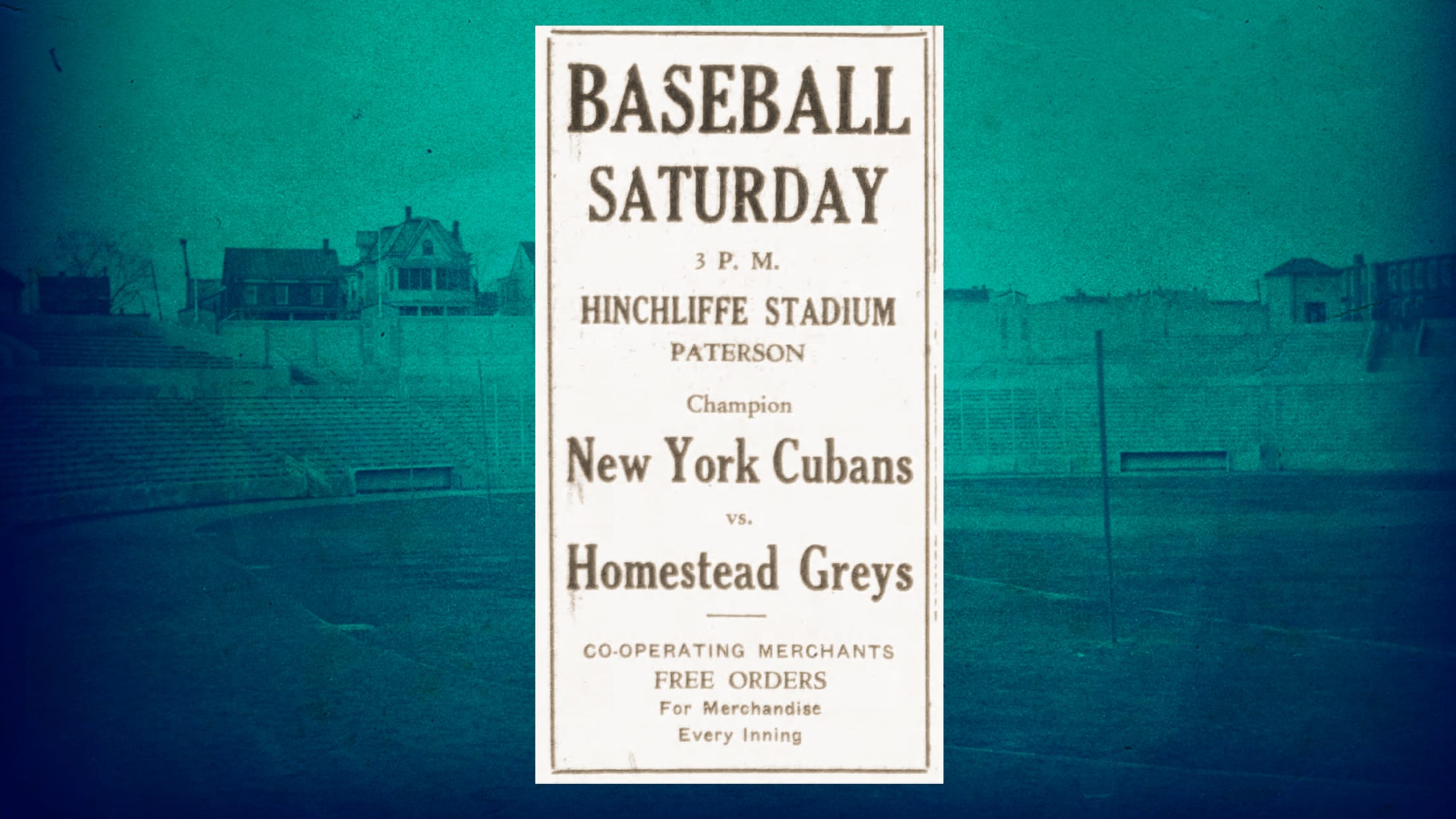

But in between those two banner events was a third significant premiere: the first baseball game. Designed as a venue for all kinds of athletic pursuits, Hinchliffe Stadium would become known regionally – if not nationally – as a baseball venue, particularly as the secondary home of three Negro National League teams in the area: the New York Black Yankees, the New York Cubans and the Newark Eagles. Each club would schedule home games at the stadium beginning with the Black Yankees in 1933 and continuing into the mid-1940s.

It hosted Negro National League games, barnstorming teams and exhibitions that included white Major League clubs in the years before Jackie Robinson. In all, 17 of the 37 Hall of Famers inducted for their ties to the Negro Leagues are a part of Hinchliffe Stadium’s history.

The New York Black Yankees

As of yet, no box score proof has been found of any Hall of Famers playing for the Black Yankees at Hinchliffe Stadium, but in 1933, the ballclub left its home ballpark in New York, Dyckman Oval, in favor of barnstorming. It played enough games at Hinchliffe for the stadium to be listed as its home ballpark in the Seamheads database.

Notable players on the ’33 Black Yankees included Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Bill Yancey, George Scales and John Beckwith. With the exception of 1936, the team would play most of its home games in Paterson through the 1938 season.

Martín Dihigo, Alex Pompez and the New York Cubans

The Black Yankees weren’t the only team to use Hinchliffe as a home field. The New York Cubans under team president Alex Pompez and player-manager Martín Dihigo used the stadium as a secondary home field in 1935 and ’36.

While he wasn’t a player, Pompez was an influential executive who helped organize the first championship series between Negro clubs and installed permanent lights at New York’s Dyckman Oval, which the Cubans used concurrently with Hinchliffe as a home field. Whether or not Pompez accompanied his team to Paterson regularly, his presence and influence was there whenever his team took the field.

Dihigo was so good at every aspect of the game that he was called “El Maestro,” or “The Master” – a Cuban contemporary of Babe Ruth, perhaps the Shohei Ohtani of his day. With data available to date, Seamheads credits Dihigo with more than 100 victories on the mound, more than 120 home runs at the plate and more than 300 victories as manager.

Ray Dandridge, Leon Day, Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, Biz Mackey, Effa Manley, Mule Suttles, Willie Wells and the Newark Eagles

Effa Manley’s impact is well known, thanks in part to her induction into the Hall of Fame in 2006. She and her husband, Abe, built the Eagles into a powerhouse that won the 1946 Negro World Series and sold the contracts of Larry Doby to Cleveland and Monte Irvin to the Giants, with each one contributing to World Series championships within five seasons of their debuts. Manley regularly scheduled Eagles home games at Hinchliffe, giving more fans a chance to see these Black stars in person.

Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson and Judy Johnson

In September 1933, the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Black Yankees squared off for the “colored championship of the world,” with the third and deciding game played at Hinchliffe on Sept. 5. Despite having these four future Hall of Famers in their lineup, the Crawfords were defeated, 6-3, in front of more than 5,000 fans, the largest crowd of the season. Walter Cannady, the Black Yankees’ second baseman and cleanup hitter, tripled and hit a two-run homer. Oscar Charleston also hit one out of the park but only got credit for a double when the umpires ruled that John Henry Russell failed to touch third and was called out.

Josh Gibson, whose home run exploits are legendary today, burnished that reputation with some impressive feats at Hinchliffe. The slugging catcher frequently played as a visitor with the Crawfords and the Homestead Grays, with several notable home runs earning ink in local newspapers. In one 10-2 Homestead victory over the Black Yankees in 1942, The Paterson News reported that Gibson, “famed as one of the greatest hitters in pro baseball (white or colored)” hit a “high, lazy clout that hit directly ON TOP of the centerfield screen, and bounced back into the Stadium. Another fraction of an inch and it would have been gone for good.”

Six Pirates, three barnstorming pitchers and a Native American legend

On May 7, 1933, the Pittsburgh Pirates had a day off between games in Brooklyn and Boston, so they detoured to Paterson. Honus Wagner, in his first season as hitting coach for his former club, was celebrated in the city where he played for the Paterson Silk Weavers in 1896-97 before joining the National League’s Louisville Colonels.

The Pirates’ starting lineup included five future Hall of Famers who played half the game: Lloyd Waner in left field, Freddie Lindstrom in center, Paul Waner in right field, Pie Traynor at third base and Arky Vaughan at shortstop. Wagner, then 59 years old and three years away from entering the Hall in its inaugural class, hit a pinch-hit double for the Paterson City Club in the ninth inning and scored in a 7-4 Pittsburgh victory.

On July 8, 1933, Charles “Chief” Bender brought his barnstorming House of David team through northern New Jersey to play the Paterson City Club. The next day, football Hall of Famer – and former New York Giants outfielder – Jim Thorpe and his barnstorming outfit, the Oklahoma Indians, played a doubleheader against those same Clubbers, as the papers called them.

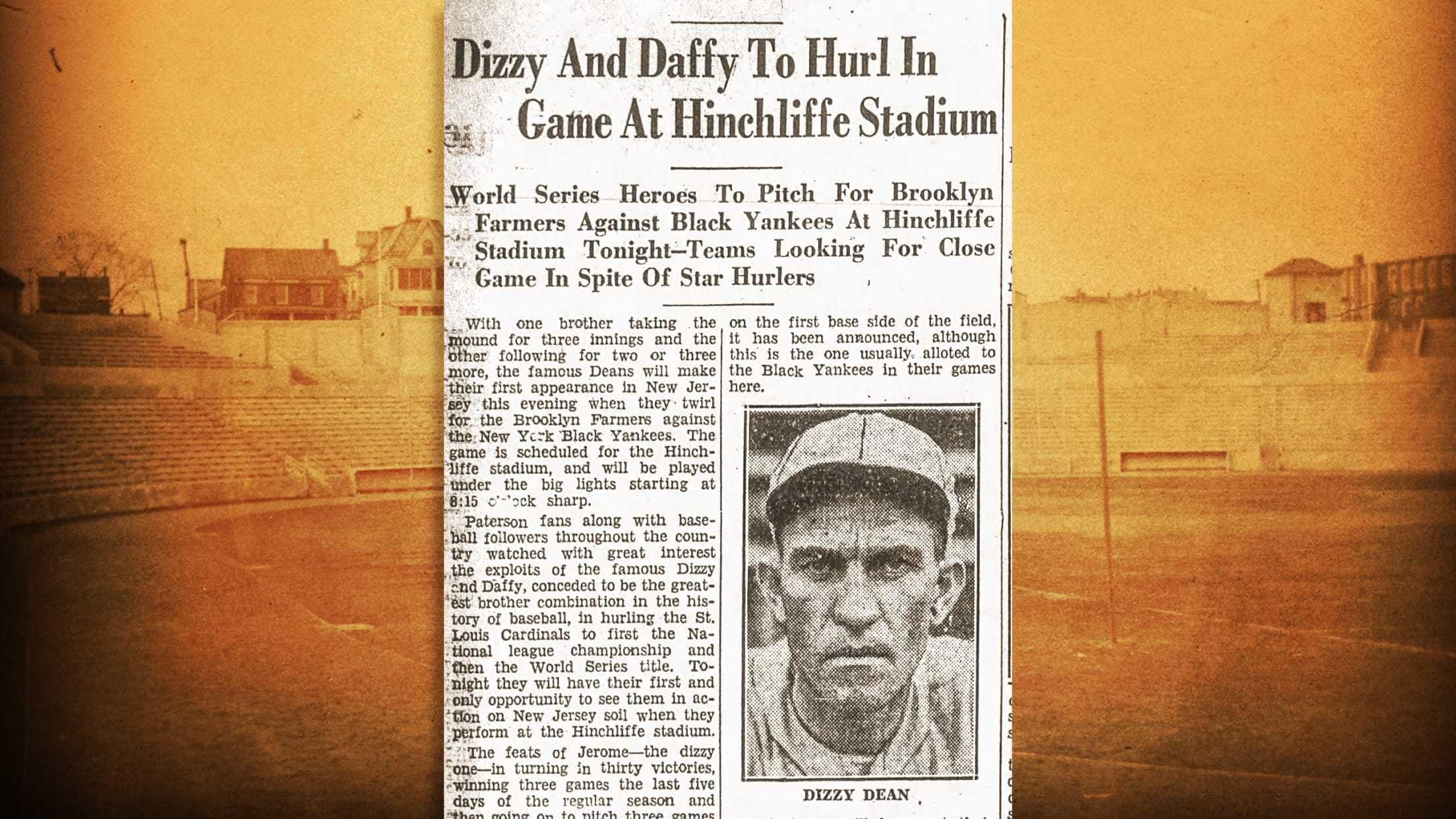

A year later, just 10 days after his Cardinals finished off a Game 7 World Series victory against the Tigers and four days after being named NL MVP, Dizzy Dean and his brother Paul (“Daffy”) barnstormed through Paterson with the Brooklyn Farmers to play the Black Yankees at Hinchliffe on Oct. 19, 1934. Dizzy started the game in right field but took the mound in the fourth, fanning three in two innings in a 10-3 victory for the Farmers.

Ray Brown, Buck Leonard and Jud Wilson

The Homestead Grays may be the first team many think of when asked to name Negro Leagues franchises, and a lot of that has to do with Josh Gibson’s nine seasons with the club (compared to his four with the Crawfords). But if Gibson was “the Black Babe Ruth,” Buck Leonard was considered “the Black Lou Gehrig,” and though researchers have only found 106 home runs to date, he was known as one of the most dangerous Negro Leagues hitters in his time.

Ray Brown is credited with 125 wins against 50 losses, a .714 winning percentage in 233 games (167 starts) that would produce a record of 306-123 over the 576 games that Hall of Fame starting pitchers averaged.

Jud Wilson was considered one of the Negro Leagues’ hardest hitters, with a nickname – “Boojum” – derived from the sound of the baseball bouncing off outfield walls after he hit it. Credited with at least 100 home runs, he also hit quite a few over the walls.

Roy Campanella

“Campy” passed through Hinchliffe as a 19-year-old catcher with the Baltimore Elite Giants in 1941. He went 0-for-3, according to one known box score, but more may yet be found because he first suited up for Baltimore at the age of 16 in ’38.

Satchel Paige

While Paige famously jumped from team to team in the Negro Leagues, and was known to have been a part of some clubs that played at Hinchliffe in the 1930s, there is no evidence yet that he appeared in a game there before pitching for parts of six seasons in the American League. But in 1966, at the age of 60 (maybe), he signed on with the traveling Indianapolis Clowns and pitch two innings at Hinchliffe without giving up a hit against a team called the New York Stars.

Babe Ruth … and boxing?

While the Great Bambino played in documented exhibition games in several northern New Jersey cities, Hinchliffe wasn’t one of those sites. But in 1946, he made one of his regular appearances as a headlining guest at an amateur Diamond Gloves boxing event, with coverage in the days leading up to the bouts promoting his attendance.

“Babe has been a highlight of the Diamond Gloves for years,” The Paterson News reported the following day. “He loves them, as he attested last night. ‘I’ve been coming over for many years, and I will keep on coming,’ he said.”

Boxing stars Jack Dempsey and Joe Louis would appear as guest referees at Hinchliffe bouts and other pugilists such as Jake LaMotta, Rocky Graziano and Max Baer would make appearances over the years.

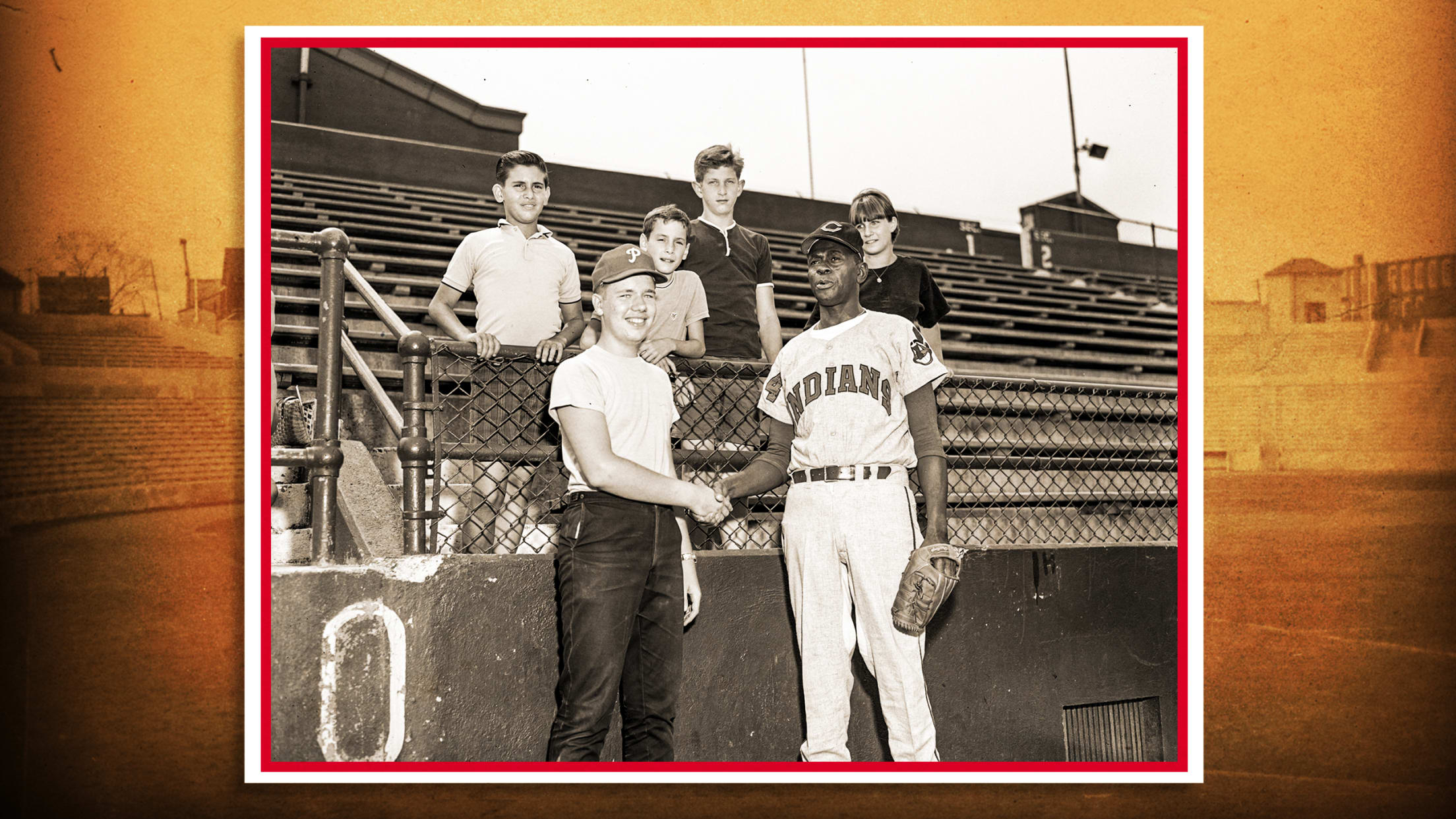

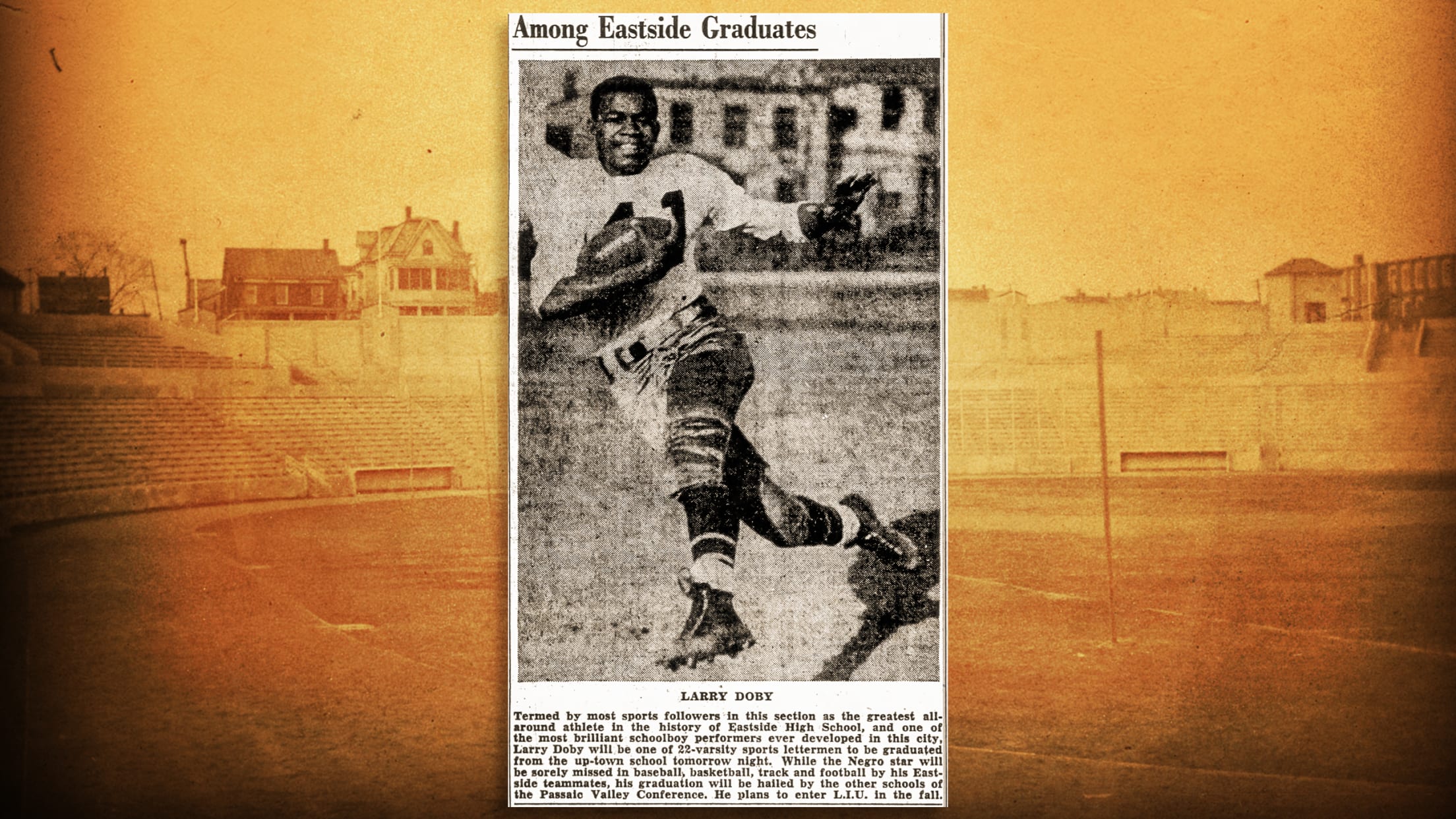

Larry Doby – before he was a professional

Before joining the Newark Eagles, Doby was a star for Eastside High School playing baseball and football and running track at Hinchliffe (as well as playing basketball in the colder months). When he graduated in June 1942, The Morning Call lamented his exit from the prep sports scene. But he wasn’t done competing. In fact, he’d already tried out for the Eagles (believed to be before a game at Hinchliffe in May 1942) and made his debut for them in a game at Yankee Stadium on May 31 – playing under the name Larry Walker to preserve his amateur eligibility. He also continued playing for semi-pro teams at Hinchliffe throughout that summer, in addition to appearing in 23 games for the Eagles.

The stadium was built at first for football, serving as the home field for Eastside and Paterson Central – and as the site of their annual Thanksgiving Day showdown. In 1941, more than 12,000 fans turned out for Doby’s last intracity rivalry game – and he didn’t disappoint, scoring two touchdowns, setting up another with a pass and kicking an extra point.

Hinchliffe was also the home of the professional Paterson Panthers and other minor league and semipro football clubs through the years.

“Bronco Bill” Schindler and motorsports

Schindler is a member of the Midget Auto Racing Hall of Fame, the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame and the New England Auto Racers Hall of Fame and is the all-time leader in motorsports victories at Hinchliffe with 52. Vehicle races were first proposed in 1934 by Ed Otto, who would go on to help found NASCAR. A 17-event motorcross was the first competition held, in June 1934, followed a couple months later by the first midget auto race.

Abbott and Costello and other entertainers

Sly and the Family Stone (Rock and Roll Hall of Fame) Duke Ellington (Songwriters Hall of Fame) and Tito Puente (Latin Music Hall of Fame) are among the notable musicians who played Hinchliffe over the years. But the headliner for this slot should go to the comedy duo of Abbott and Costello.

Both were Jersey-born entertainers, Bud Abbott from Asbury Park and Lou Costello from Paterson itself. The two performed several times at Hinchliffe in the 1940s, perhaps reviving their popular “Who’s On First?” routine, which debuted as a radio sketch in 1938 and later appeared in the 1945 film “Naughty Nineties,” featuring a “Paterson Silk Socks” banner on the ballfield backdrop.

Who's on first?Abbott and Costello perform the classic "Who's on first?" baseball sketch in their 1945 film "The Naughty Nineties" first performed as part of their stage act.

Posted by Philip Miles on Thursday, August 13, 2009

While Abbott and Costello are inducted into the National Comedy Hall of Fame and the New Jersey Hall of Fame but not the Baseball Hall of Fame, their routine is in Cooperstown. A gold record of “Who’s on First?” was put on display in 1956, prompting Costello to quip, “This is many times better than getting an Oscar.”

With a rebuilt Hinchliffe Stadium, there is now the chance that the number of Hall of Famers to play there will grow. Nazier Mule, a fourth-round Draft pick of the Cubs in 2022, didn't get to take the field there as an amateur, but he's since learned some of its history.

“Growing up, it was just a building, you know?” he said in a video on andscape.com. “It was a broken-down building that looks like the same as any other failed project. And that’s not what it should be ... [I]t should have been memorialized, and it should have been taken seriously as something that was special.

“Now that it’s being reconstructed and things like that, I feel as though the younger generations are going to get as much joy out of it, if not even more than all of the older generations have.”