This rookie is living his father’s MLB dream

LOS ANGELES -- When asked how many hits his father, Cuban baseball legend Lazaro Vargas, recorded during his illustrious career in the Cuban National Series,

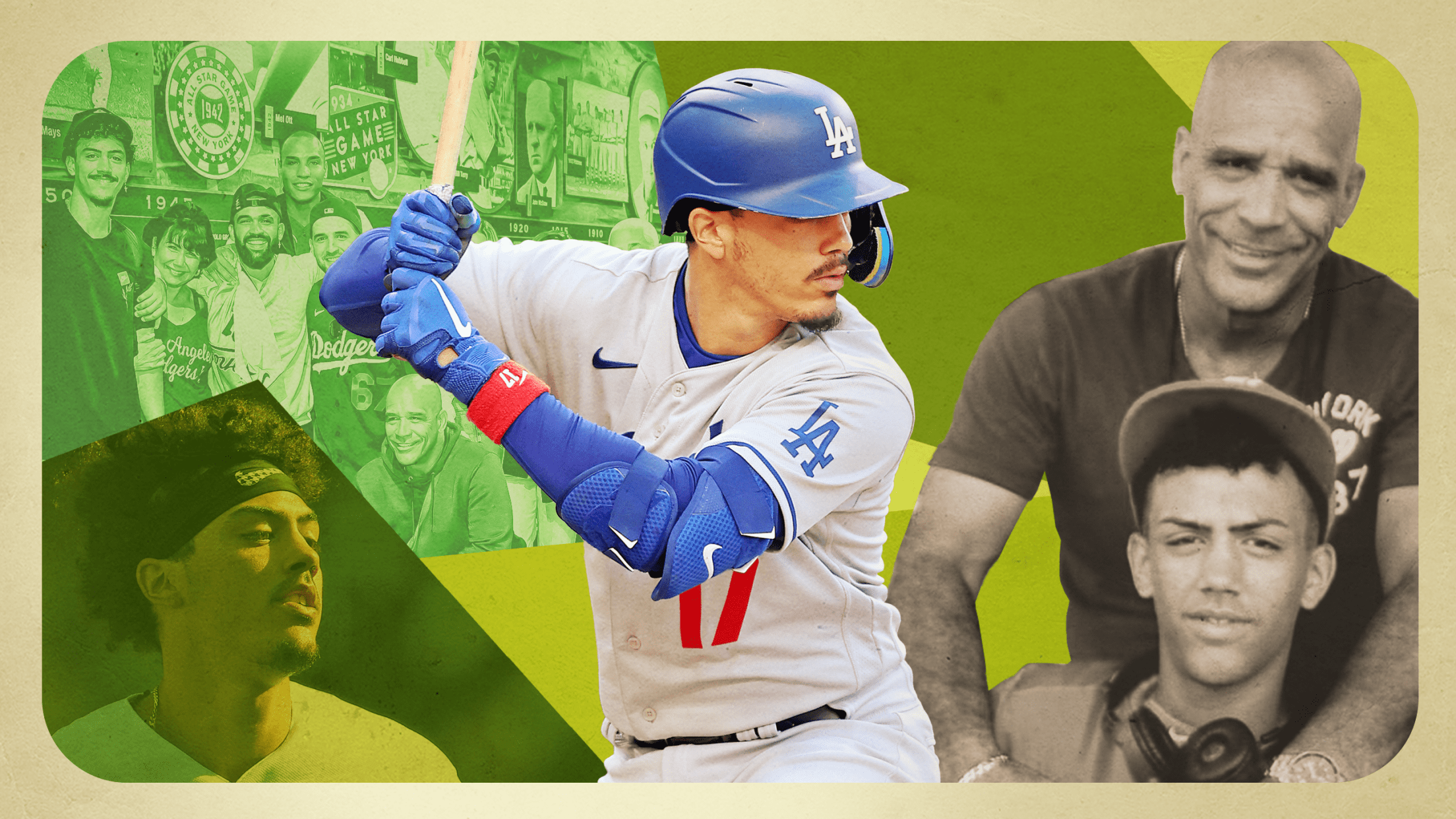

And yet, despite a high level of admiration for his father’s decorated career, Miguel, from a very young age, wanted to create his own identity.

Miguel never emulated Lazaro’s batting stance or dragged his bat through the dirt from the dugout to the batter’s box as his father was known to do. He avoided wearing No. 20, the number Lazaro made famous during his playing days for Industriales in Cuba.

They were small things, but purposeful, as he tried to differentiate himself from the legacy his father created.

“I wanted to be me,” Miguel said in Spanish. “I didn’t want to be looked at as just his son. I wanted to be as good as him or even better.”

And now? Miguel has carved his own path to baseball stardom, and his father could not be more proud.

“He’s definitely better than me,” Lazaro said. “He has better tools than I had. He hits more than me, he runs faster than I did, and he’s so much stronger than I was.”

Feeling pressure from being the son of an accomplished player isn’t uncommon. However, in smaller nations like Cuba, the level of expectation is heightened significantly. The Gurriel brothers dealt with similar noise in Cuba and after they defected. In fact, the Gurriels changed the spelling of their last name (it was originally Gourriel) simply to distinguish themselves from their father, Lourdes Gourriel, an Olympic gold medalist and Cuban star for two decades.

“I really felt [the pressure] when I was starting out in Cuba,” said Marlins first baseman

Miguel was still a toddler when Lazaro wrapped up his 16-year career for Industriales in Cuba. But as he grew older, he learned how accomplished his father had been in the sport.

Lazaro finished his career with a .322 average, recording 991 career hits in just 872 games. The stats, including a ridiculous 136 hit-by-pitches over his career, speak for themselves. Among players in the National Series, Cuban’s top professional league, Lazaro is considered one of the two best Cuban-born third basemen ever, along with Omar Linares.

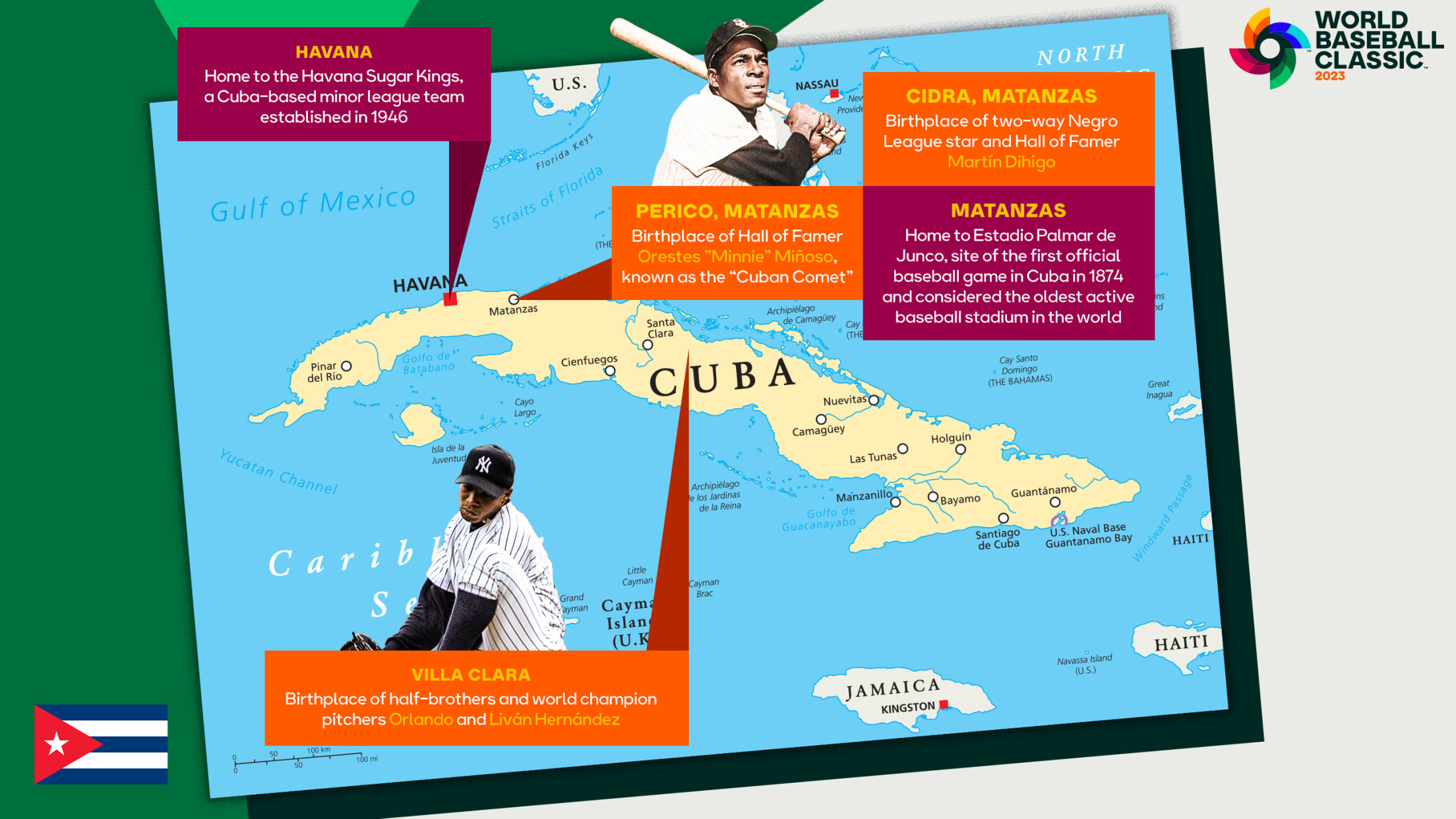

As good as he was in Cuba, Lazaro really made his mark in international play.

In 1992, Lazaro and the Cuban national team traveled to Barcelona as the favorites to take gold during the Summer Olympics -- and that’s exactly what they did. Lazaro went 17-for-37 in the tournament and became the first player to hit for the cycle in the Olympics, doing so in the gold medal game against Chinese Taipei.

Two years later, Lazaro suffered a devastating knee injury. Doctors told him that he would have trouble walking for the rest of his life and that his playing career was over.

And yet, one year later, a healthy Lazaro won the batting title in the Cuban National Series, helping him secure a spot on the 1996 Olympic team. He went 12-for-35 in that tournament as Cuba won a second consecutive gold medal. Lazaro became so popular on the island that he is featured on the 15-cent postage stamp in Cuba.

“I can assure you that he never took three weeks’ worth of pitches like Miguel did in Spring Training this year,” joked Tigers manager A.J. Hinch, who, as a catcher for Team USA, competed with Lazaro in the ‘96 Olympics, and was referencing Miguel not being allowed to swing in Spring Training for a few weeks because of a fractured right pinky finger. “That country in that era was producing incredible baseball talent that never got to see the Major Leagues.”

Lazaro said the thought of playing in the United States didn’t cross his mind much. Wondering “what if” is something he occasionally does now, but there’s no regret about never leaving the island to pursue other opportunities.

It was a different era, Lazaro noted, as it wasn’t until René Arocha defected in 1991 that players even discussed that possibility. By that time, Lazaro was already 27 years old.

“I didn’t know how people lived in the United States. I didn’t know what the system was like,” Lazaro said. “I never really thought about it. If I did come to the United States, maybe Miguel wouldn’t have been born. That’s how life is.”

Miguel always knew he wanted to play in the Major Leagues. Growing up, he was often the best -- and youngest -- player on his teams. When he was 14, Miguel joined Industriales in the Cuban National Series.

His teammates included Lourdes Gurriel Jr., Yuli and

“One day I had a take sign on, and [Miguel] swung with three balls and no strikes and I had to bench him,” Lazaro laughed. “The day I finally got to play him, I told him I was going to play him but not just for show. I told him he better not strike out or let a bunch of ground balls get by him. That day he played really well, and that’s when I knew he had all the tools and the heart to play this game at a high level.”

Playing on that team as a 14-year-old also proved to Miguel that he was capable of competing at a higher level. Later that year, he represented Cuba in a U15 tournament in Mexico. After that tournament, Miguel approached Lazaro and his mother about his desire to leave the island and pursue a professional career in the U.S.

A year later, Miguel went to Japan for a U18 tournament. When he returned to Havana, Miguel was only thinking about showing off his new shoes and backpack to his friends.

Instead, two days before his 15th birthday, his parents sat Miguel down and notified him they were leaving for Ecuador, the first step to helping him realize his lifelong dream.

“I had a lot of emotions, obviously,” Miguel said. “I think we all made the decision. My mom definitely cried when she left her mom there and her family. It’s hard for all of us. But I was ready, and I knew the moment was going to come when the time was right. I just wanted to play in the Majors.”

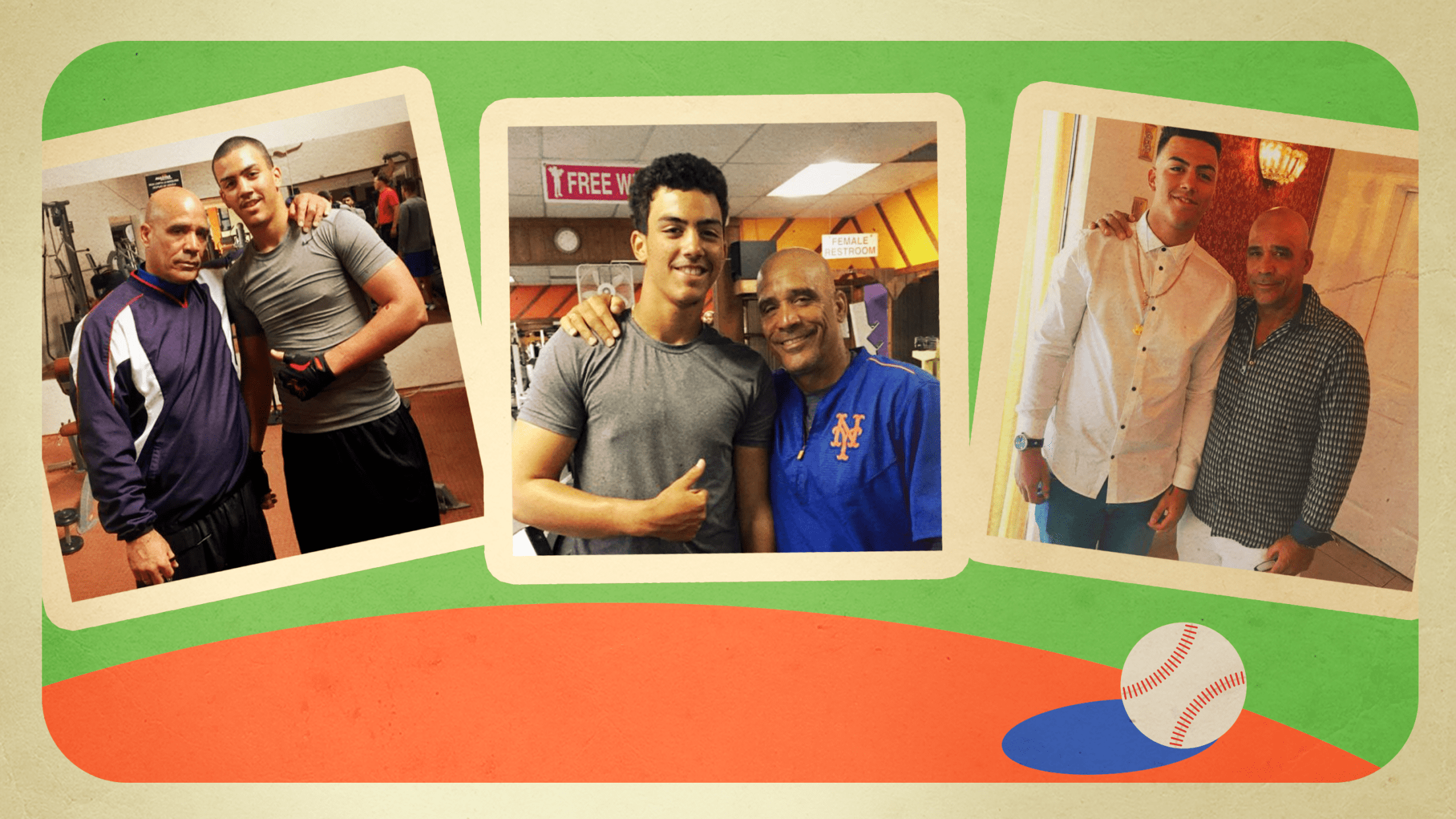

After leaving Cuba, the Vargas family stayed in Ecuador for six months before going to the Bahamas. Lazaro trained Miguel, along with Miguel’s older brother, Alejandro, at a nearby facility.

“I remember that I would wake up in the morning, we would practice in the morning, I would go back home to eat and take a nap,” Miguel said. “Then at night I would go to the gym. That was my life for a year and a half.”

Once in the Bahamas, Miguel believed he would sign immediately after turning 16, which is customary for top international prospects. Instead, he endured an emotional two-year journey full of ups and downs.

“I remember telling my parents I didn’t want to play anymore,” Miguel said. “The life of Cuban players is tough. You don’t see a lot of friends and all you have is baseball. There’s always the unknown of whether you’re going to sign or not.”

As those thoughts crept into Miguel’s mind, Lazaro advised him to think about things for a week. If he still felt that way afterward, the family would adjust accordingly. Lazaro then reached out to White Sox field coordinator Mike Tosar, who at the time was in the Dodgers’ international scouting department.

Tosar had scouted Miguel and was impressed with his bat-to-ball skills. He flew to the Bahamas, along with Ismael Cruz, the Dodgers’ vice president of international scouting.

They arrived to find very poor field conditions. A storm had ripped apart all the fields in the area. The backstop was on top of home plate. There was no outfield fence. And the grass was up to their knees. Because there was nobody else around, Miguel’s mom was in the outfield shagging fly balls while Lazaro pitched to their son.

Miguel wanted to show off his speed despite the field conditions and he ended up pulling a hamstring in the process. He still impressed the Dodgers with his tools and desire.

“He was hitting balls into a house,” Tosar recalled. “We couldn’t really get the distance, so we went on a distance-tracking app through GPS. We saw home plate, we saw the roof and where the ball hit and we marked it and it was over 400-something feet. He must’ve been 17 at the time. It was legit.”

At the time the Dodgers only had $300,000 to offer Miguel because they had exceeded their spending total internationally the year before. That amount was below what he was hoping to sign for, and the Dodgers knew he was worth more than that.

But with other teams, including the Dodgers, awaiting Shohei Ohtani’s international decision that year, a lot of organizations weren’t able to spend as much money in smaller countries such as the Bahamas. That affected Miguel’s negotiations and his potential suitors.

With no offers on the table, the Dodgers pounced at the opportunity to sign Miguel at a lower price, and the young Cuban infielder took another big step in his life, signing with the organization.

Over the last five years, Miguel has built himself into one of the top prospects in baseball, hitting 49 homers and posting a .878 OPS during his Minor League career.

This season, Miguel has become the everyday second baseman for the Dodgers. Like any rookie, he has had his fair share of growing pains but has shown improvement as the season has progressed. What his ceiling will be remains to be seen.

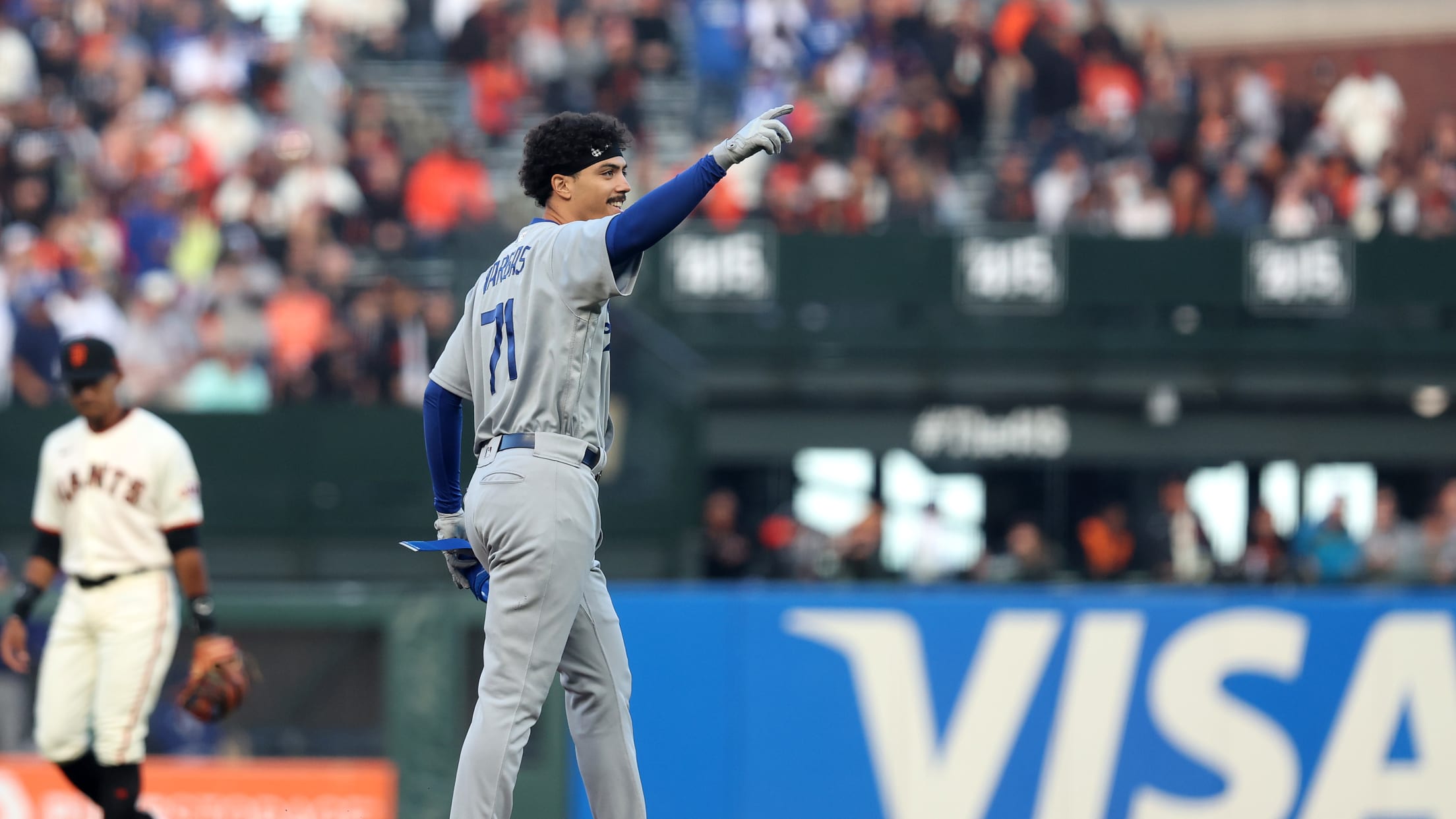

The highlight of his career thus far, though, came on Aug. 3, 2022, when the Dodgers called the then-22-year-old up to the Majors.

In his first MLB at-bat, Miguel lined an RBI ground-rule double off veteran right-hander Alex Cobb. As he touched second base, Miguel glanced up at the family section at Oracle Park and smiled. The camera panned to the Vargas family. Right in the middle was Lazaro, who raised both of his arms in triumph as he sported a blue Industriales jersey.

“I wanted to represent my dad,” Miguel said. “I knew that if I could do it, that means he could’ve done it, because I listened to everything he told me when he trained me. In my mind, I always knew he was capable of playing in the big leagues.”

At that moment, Lazaro wasn’t the Cuban baseball legend most people tell stories about. He was just a dad, watching his son play the game they both love. That was the real dream come true.

“Honestly,” Lazaro said, gathering himself, “it’s way more important, and I feel even more proud seeing Miguel live out this dream than if I would’ve accomplished it.”