Hometown Series: Walker Buehler

As leaves throughout Kentucky are turning shades of red and yellow, the coniferous trees at Ecton Park remain a vibrant green in the November sunlight, towering over the parking lot and beyond the outfield fence where Walker Buehler first made a name for himself in Lexington. It was here, more than a decade ago, more than 2,000 miles east of Los Angeles, where the Dodger All-Star earned his version of a Hollywood star on the ground.

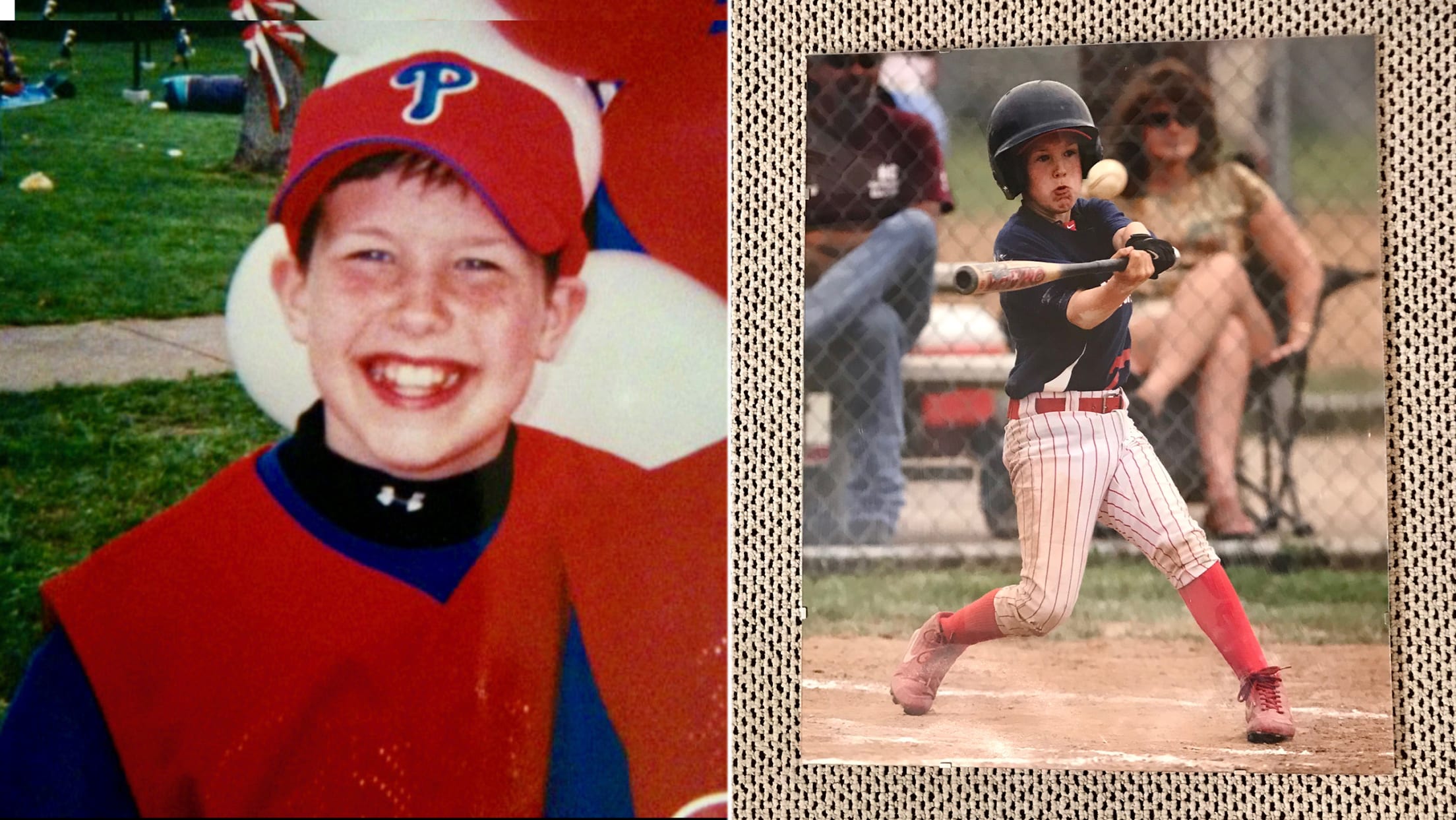

Horse racing and University of Kentucky basketball dominate the discussion around town, but for the young baseball players in the area, Ecton Park is equally intertwined into the fabric of the city. Buehler’s not a particularly nostalgic person, but the park is a part of him. He says it possesses a mystical feel. It’s where he played games as a Little Leaguer, sometimes walking from his home a few blocks away, setting the single-season strikeout record and winning the Home Run Derby. It’s where he returned as a high schooler, occasionally getting into trouble with his friends while goofing around at night. On the back of the concession stand, Buehler’s name can be found among the 11-and-12-year-old Eastern Little League All-Stars and district champions.

A few steps over, his individual accomplishments are inscribed into a brick on the ground:

Walker Buehler

2001–2007

Season K Rec 140

HR Derby Champ

“I felt like a king back then,” Buehler says. “You set any kind of record at the Little League where you’ve been running around for years and years, it was a really cool deal for me at the time.”

At least it was while he had the record.

“I think it was just shattered by a young kid, which I didn’t really like,” Buehler says. He smiles. It’s unclear if he’s joking. “I had it for a little while.”

Buehler isn’t sure where his competitiveness and self-confidence stem from, but the traits were evident then as a kid as they are now, according to both Buehler and those who knew him. His father, Tony Buehler, wonders if they developed from Walker always playing against kids who were older than him.

“He always had to compete,” Tony says. “I think that drove him.”

In Walker’s pre-teen days, the best players were shortstops. They were the ones who could throw across the diamond on the fly. That’s where he played for one of his Little League coaches, Laurance VanMeter, who is now a Kentucky Supreme Court judge and was then a Court of Appeals judge in Kentucky. With the latter job, VanMeter could schedule his workload more easily to find time to coach games. The kids called him Judge.

Walker played for the Phillies and was VanMeter’s first selection of the second round. Back then, Walker could hit and field and throw, but he hadn’t yet separated himself as a superstar. No one could’ve predicted what Walker would become, but no one could question his competitiveness, either.

“He’s 9 years old, it’s the end of the game, and he’s feeling bad,” VanMeter begins. “A kid for the other team stole second, slid head first. That’s against the rules, but he was safe. Walker nudges me and goes, ‘Judge, he slid head first.’ I’m like, ‘You’re right.’ I went up, went out to the umpire, challenged the play. … It was right. We won the game, so he won the game ball. He wasn’t even in the game.”

Over the years, VanMeter has coached lawyers, doctors, veterinarians, fighter pilots and two pro baseball players — one was Patrick Brady, a 31-year-old who made it as far as Triple-A; the other was Walker. Watching Walker now, VanMeter admires how cerebral his former pitcher remains, staying into the game whether or not he’s on the mound. He also notes the leg motion in Walker’s delivery — VanMeter says it’s the same one he had as a kid.

“For me, watching Walker pitch … it’s like watching one of my own kids,” VanMeter says, though he won’t take credit for the numerous successes Walker has experienced since his time in the Eastern Little League.

“The joke that Judge always makes is that he stayed out of my way,” Walker says.

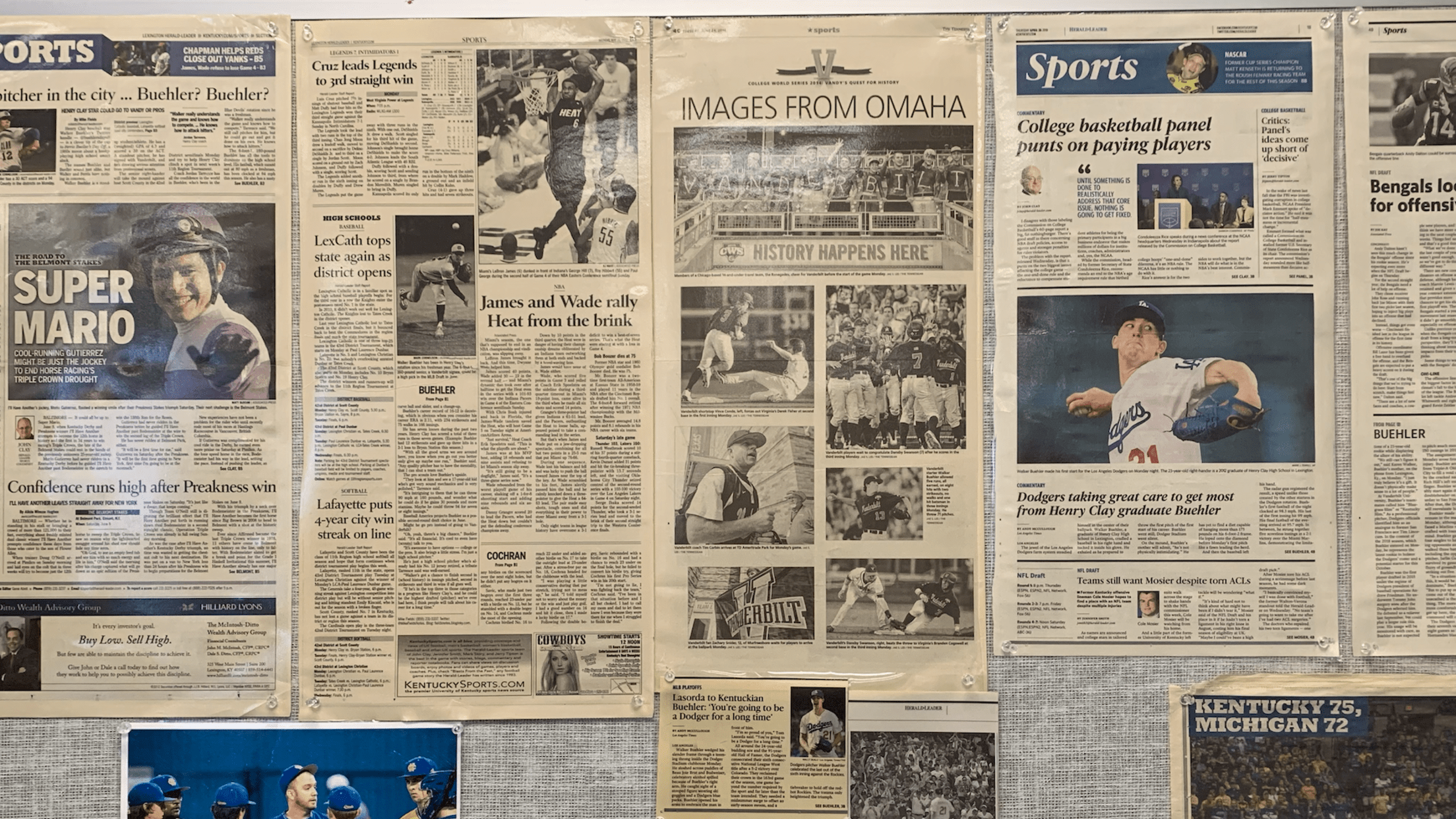

Newspaper articles about Walker, from high school to Vanderbilt to Los Angeles, adorn the walls of Jordan Tarrence’s classroom at Henry Clay High School, where Tarrence has served as head coach since Walker’s sophomore year at the school. He reads about Walker’s confidence and knows the Dodgers have the same player he knew in high school, the one whose №12 is retired along the right-field wall.

By the end of Walker’s tenure, his talents had been established enough that his number was retired while he was still in school.

“I actually played a game with my own jersey retired out there, which is a little odd,” Walker explains. “It just happened that way. But no, it’s pretty cool. At Henry Clay, you have to be a four-year starter to get your name on the wall.”

Walker knew early on he wanted to attend the school, which was named after the historic Kentucky statesman whose estate is still among the landmarks of the city and whose memorial skies above the Lexington Cemetary, clear to see for anyone driving by. Henry Clay High School built a reputation as a strong baseball program, one that had already churned out Major League talent. Opposite Walker’s №12, tucked close to the right-field foul pole, hangs the №10 of former Dodger John Shelby. There were others, including Collin Cowgill. In the eighth grade, Walker transferred so he could attend the school. He made the team that year.

By Walker’s freshman season, it was clear to those around him he had potential. By his sophomore year, it was clear he would be special, helping the Blue Devils reach the regional finals. Tarrence remembers the progression of Walker wanting to play college baseball, then wanting to play Division-1 baseball — perhaps at Miami (Ohio), where Walker’s parents went to school. Then he was invited to play travel ball with the esteemed Marucci Elite club. Then SEC offers started pouring in.

“I don’t know if he just got used to it, but it was pretty impressive that a 17-year-old kid didn’t get overwhelmed and didn’t get rattled by the attention and the amount of people there watching,” Tarrence says.

By his junior year, Walker’s stock soared and scouts flocked to Lexington. They would text Tarrence just to hear when Walker was throwing a bullpen session. Occasionally, Tarrence would drive Walker to games. One time, the two of them went the wrong way on the interstate and arrived late. The other team already knew who was pitching for Henry Clay based on the number of scouts already there.

“It was a pure projection type guy, but everything worked real easy, arm was really loose, had the arm speed,” says Marty Lamb, the Dodger scout who eventually drafted Walker out of Vanderbilt in 2015. “He could spin the ball and he commanded the ball, which for a high school young kid you don’t see happen very often.”

The eyes glued to his performances never fazed Walker, who already had a curveball and slider few high school pitchers could rival to go along with a fastball that continued to rise in velocity into the 90s.

“People always ask me, ‘Did you see it coming?’” Tarrence says. “I don’t think anybody could’ve predicted this guy — he’s 6–1, weighs 180 pounds — that he’s going to throw 100 mph. But he had the tools and the mechanics to get to that level.”

To that point, Walker credits the man who’s been his pitching coach nearly his whole life.

Ben Shaffar was a former sixth-round pick of the Cubs out of the University of Kentucky. He reached the Triple-A level, but when injuries shortened his career, he decided to return to school.

It was then that his former college catcher started asking Shaffar to help coach pitchers on a travel team for 13- and-14-year-olds. Just three months out of pro baseball, Shaffar wasn’t sure. But he thought it would provide a chance to give back. One of those kids was Walker Buehler.

“Walker was super competitive,” Shaffar says. “At that time, still undersized and developing, but he knew how to pitch. About a year later, he came to me in the private academy and was struggling mechanically and having a little bit of arm issues at the time, and that’s when we really started our relationship.”

For most of Walker’s life, his father lived in Cincinnati while he grew up with his mother in Lexington. The presence of Shaffar not only added another baseball mind, but another mentor. The fact that Shaffar decided to take countless hours out of his day — time that was valuable to Shaffar, who had a wife and kids — meant a lot to Walker. His father recognized that.

“I can’t give Ben Shaffar enough credit, even going back to Little League, just everybody that contributed molding him to who he is today,” Tony says. “It’s a big puzzle. There’s a lot of pieces.”

On the baseball development side, Shaffar was a significant piece.

He worked on building Walker’s Major League pitching foundation from a mechanical standpoint — the repeatable delivery, the backside stability. By Walker’s sophomore year at Henry Clay High School, Walker and his family had helped convince Shaffar to join the school as a pitching coach. Shaffar was all in, implementing a pro-style approach complete with bandwork and a strict diet. He would bring bananas and granola bars to the school, sticking them in Walker’s locker to make sure he’d eat them.

“I loved all the kids I coached, but it was an investment in him,” Shaffar says. “I recognized this was a kid that has an opportunity, and if I can pour a little more time and energy into him, he could be something really, really special.”

Like Tarrence, Shaffar says he couldn’t have predicted the eventual triple-digit heat Walker would conjure from his right arm. No one could have. But Shaffar had seen enough by Walker’s sophomore year to believe his pupil could get drafted. By Walker’s junior year, the two were having conversations about whether going to college or the pros would be best.

“By his senior year, we were already saying, ‘You can pitch in the Major Leagues, and you can pitch for a long time,’” Shaffar recalls. “The growth that he had physically from his junior through his senior year, you saw a big leap. That’s when the velocity started creeping into the low-90s and the action on the pitches was explosive. Everything he threw came out of pretty much the same arm action — and granted, we worked hard on that.

“When he started throwing everything out of that same delivery and same slot, I’m sitting there going, ‘This is what I watched with the Cubs, Phillies, Reds or Pirates when I played.”

By then, Walker had developed not only into one of the top players in Kentucky but also essentially into another assistant coach at Henry Clay. He remembers making practice plans, highlighting the games he was going to pitch in. Walker even helped design the jerseys that Henry Clay wears today, according to Tarrence.

“It’s just funny looking back and how important all those little things felt at the time,” Walker says. “At the time, they were important to us.”

Tarrence says the kids who have followed Walker at the school consider the former Henry Clay standout a legend, and Walker’s success lends credence to Tarrence’s words when he explains to his players what it takes to reach the next level. Around the area, Tarrence has noticed Dodger hats and shirts becoming more visible. During Walker’s start in the 2018 World Series, firing seven scoreless innings against the Red Sox, Tarrence remembers at least 30 teachers at Henry Clay wearing Dodger blue.

Watch parties at local bars are common when he’s on the mound, particularly if it’s a playoff start.

“The first time I heard them chanting ‘BUEH-LER’ in the stands at Dodger Stadium was kind of a moment I’ll never forget,” says Karen Walker, Walker’s mother. “Kind of took my breath away. It’s everything you could imagine. It’s amazing and exciting. It’s very surreal. But I don’t know, there was just something always in me that kind of knew that Walker was destined for greatness. He just has always been so fixated on competing and being the best and doing his best and pushing himself — most people, you can’t teach that kind of drive.”

That drive has created a city of Dodger fans on the other side of the nation, so much so that it’s hard for Tarrence to wrap his mind around. The same way he grew up revering Greg Maddux, Tom Glavine, John Smoltz and his favorite Braves pitchers, other kids are revering the player he used to drive to games.

“I think he has a chance, 20 or 30 years from now, he might be the greatest player to ever play that came out of Lexington,” Tarrence says.

A sizable crowd at Dodger Stadium might result in 50,000 people chanting Walker’s name. That’s about one-sixth the population of Lexington, which its residents describe as either a small city or a big town. It provides refuge for Walker. A sense of comfort. Of Buehler’s 10 closest friends growing up, he says about half have remained in Lexington. The rest aren’t far away.

In this town of 322,000, the pressure on one of baseball’s most clutch young performers evaporates. Lexington is home, always has been, and the people there still closest to him have been by his side long before he was sending the Dodgers to a division title in a tiebreaker game or posting a 0.71 ERA in the 2019 playoffs.

It’s a small enough town that he’s often recognized but rarely bothered. If there’s a prominent landmark in the city, Walker can reach it without a map. If there’s a prominent person in the city, chances are Walker knows him or her. He used to live on the same street as Kentucky football offensive coordinator Eddie Gran. Nothing is bigger than Kentucky basketball, though. The Wildcats play at Rupp Arena, named after legendary Kentucky basketball coach Adolph Rupp. Adolph’s grandson, Chip Rupp, was one of Walker’s Little League coaches.

“Everyone kind of knows each other,” Walker says. “Everyone goes to the same spots.”

One of Walker’s favorites is Suggins Bar & Grill, less than a 10-minute walk away from Ecton Park and his childhood home on Lakewood Dr. Like most bars and restaurants in the area, horse racing mementos are scattered across the walls. In middle school, 20 to 30 students would pack into the back of the restaurant so they wouldn’t interrupt the rest of the customers. The waitresses knew the kids by name, knew their parents and knew what they wanted to eat.

Two of those kids were Walker Buehler and McKenzie Marcinek. They met in elementary school, began dating in high school and have been together since. They’ve long expected to get a house together in Lexington, and they’ve now fulfilled that dream. The short jaunt to Suggins is now a 20-minute drive from their new place on the north end of town, but it’s one they still make.

“The whole thing behind Suggins is it’s something we’ve gone to basically our entire life,” Marcinek says. “It’s comfortable and home. The food’s good. It’s a small restaurant, so every time you’re in there you basically talk to everyone that’s sitting there and eating. We went every Friday in middle school.”

Suggins offers a Kentucky staple — the “hot brown,” which Walker explains is an open-faced turkey and bacon sandwich. But on a Saturday afternoon with his girlfriend, father and stepmother, Lucy, Walker suggests the chicken finger salad as he shares an order of fried banana peppers and cheese fries with his family. Minutes into the meal, he recognizes an old acquaintance walking in and says hello. Soon after, a young softball player named Elizabeth is introduced by her grandmother. She asks for a picture with Walker, who’s happy to oblige. They smile for the camera. Walker’s father is smiling, too.

“We’ll enjoy the ride while we’re on it,” Tony says. “But the person that he is, the man that he’s become, how he treats people, how in Spring Training he’s running through the crowd and he’ll stop and sign autographs for 40 minutes for kids … that’s what I’m most proud of.”

Sports have always provided a bonding point for Walker and his father, who bears a close resemblance to Walker apart from standing a few inches shorter. Walker grew up playing baseball, basketball, football and lacrosse. For Tony, it was baseball, basketball and golf.

“I went to college, and you guys can see me — I’m 5–8 1/2, 150 out of the shower — so that wasn’t in my cards,” Tony says. “But I’ve always been athletic, so I hope I passed some of that to Walker. But golf is something you can compete and play an entire life. That’s my sanctuary.”

“We started playing golf, my dad and I, around the house,” Walker recalls. “We’d play with wiffle balls and go around the house twice and, ‘There’s the hole.’ He was a really good player for a long time. His favorite story, he shot 67 at one point at a TPC course and he doubled 17, so it should’ve been better than that, apparently.”

It becomes clear where some of Walker’s traits may have originated.

“What I love about (golf) is, it’s all on you,” Tony says. “If you bet, you’re betting on yourself. But that competitiveness still drives you. Even though I’m 51, I love the competitive side of it.”

When Walker has a club in his hands, his majestic swing and power make it obvious why he won a Home Run Derby at Ecton Park and thrived offensively with the bat in addition to his pitching work at Henry Clay High School. This past summer, Tony says Walker beat him on the golf course in Denver for the first time, as much as it pained him to admit.

“Whatever he sets his mind to, he’s going to be successful at,” Tony says. “I don’t know where it came from — I always say he overcame his gene pool — but he’s got it. Whatever he embarks on, he works hard at and he plows energy and effort into it so he can maximize his talent. That’s what it takes.”

Buetane on the course, too. pic.twitter.com/YX3gRY0s45

— Los Angeles Dodgers (@Dodgers) November 11, 2019

* * * *

Two days before his second annual charity golf tournament, Walker is standing in the kitchen of his new house wearing a long-sleeved shirt, sweatpants and Nike shoes. Winter has arrived early, and he’s hoping the rain and wintry mix set to hit later in the week hold off long enough to keep the event unharmed. But right now, the fireplace is on and he looks almost as comfortable as his French bulldog puppy, Nala, an Opening Day acquisition who has cuddled up on a blanket on the couch, wholly unbothered by the 40-degree temperatures outside.

Tony is helping Walker put the finishing touches on the goodie bags sprawled out on the kitchen table, packing Nike sunglasses, Srixon golf balls and travel-sized bottles of Woodford Reserve into Dooney and Bourke dopp kits.

Last year, in its inaugural season, Walker used his charity tournament to raise money for Kids Cancer Alliance, a cause close to the Buehler family. Walker’s uncle, Matthew “Pig” Buehler, passed away from cancer years after battling the disease as a kid.

“We were super close,” Walker says. “My little brother and sister are five and six years younger than me and the other one’s 12 … they didn’t get to know him the way that I did — just an awesome, awesome fun guy. Kind of had a second chance at life after beating Hodgkin’s Lymphoma as a child. (He was) so happy-go-lucky and one of my best friends.”

Tony powers through when reminiscing on Walker’s numerous successes on a baseball field, but when he thinks about Walker using his platform in honor of his late brother, he begins to crack.

“Walk was the only nephew or niece that my brother knew early on,” Tony says. “The ability for my brother to be part of Walker’s foundation … we all carry it. We all carry my brother Matt, Pig. For Walker to do what he does before every start and scratch ‘P-I-G’ in the dirt behind the mound, it means a lot.”

Walker would suffer another loss in the family when he lost his aunt to a brain aneurysm just days before the Dodgers’ Game 5 matchup in the NLDS. Next to “P-I-G,” he also scribed his aunt’s initials into the dirt before the game, according to his father. He went on to allow one run in 6 2/3 innings.

“He steps on the field, he flips a switch, and he’s a different dude,” Tony says. “But he gets back to the hotel, or with us, he’s just Walk. That’s what I admire about him so much.”

Going forward, Walker plans on using his tournament to continue raising money to battle childhood cancer. But this year, there was another foundation close to Walker’s heart. All of the proceeds went to “Field of Genes,” a campaign started by his teammate Rich Hill, who lost his son Brooks to a rare brain condition and is raising money to further research atypical genetic diseases to help other families searching for answers.

The weather held off long enough to get the tournament finished without delay. Hill attended, as did Walker’s teammates Will Smith and Josh Sborz and many of his former coaches, including Tarrence, Shaffar and VanMeter.

“They’re not forgotten,” Karen says. “Walker is the embodiment of all of that support. They’ve all rallied around him. When he’s in the newspaper or he’s on TV, it’s a feather in the cap to all those people who had a part of it, and Walker’s very mindful of that.”

But he’ll do it with his own touch.

As part of the effort to raise money for his teammate, Walker held a silent auction at the event, during which VanMeter won a signed Buehler jersey. On the “1” of his №21 Dodger jersey, Walker penned his autograph. On the “2,” he wrote his old coach a note:

“Judge, Thanks for not messing me up!”