Presidents and the Polo Grounds: Why do we stretch in the middle of the seventh inning?

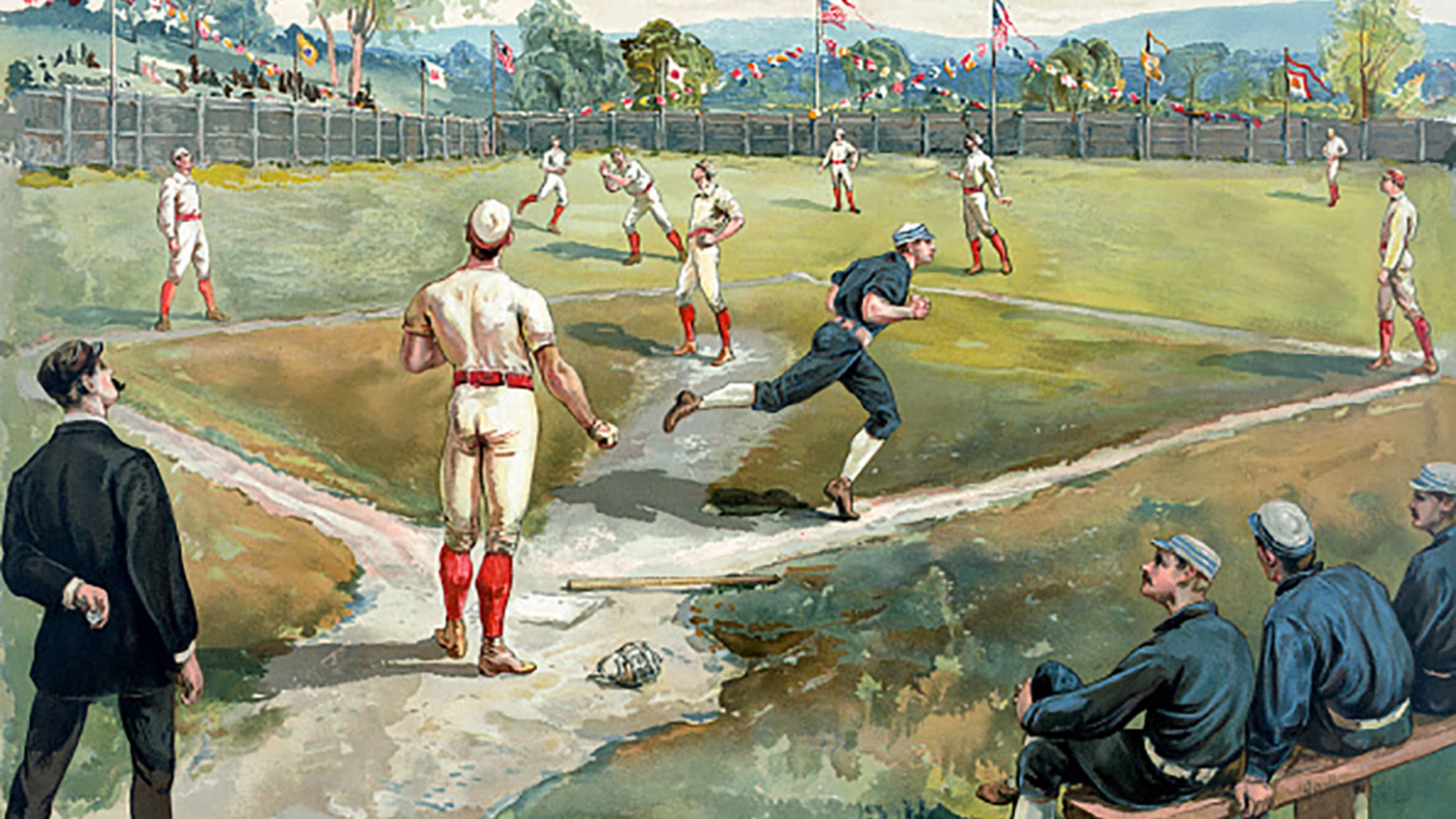

It's a little silly, if you think about it: After the top half of the seventh inning, the entire ballpark gets up, shakes out the limbs and maybe even sings along until the game resumes -- a big, deep breath to prepare ourselves for the end. And yet, like a lot of silly little rituals, the seventh-inning stretch has become a central part of baseball's vernacular, so deeply embedded in American pop culture that it's even got its own Air Bud movie.

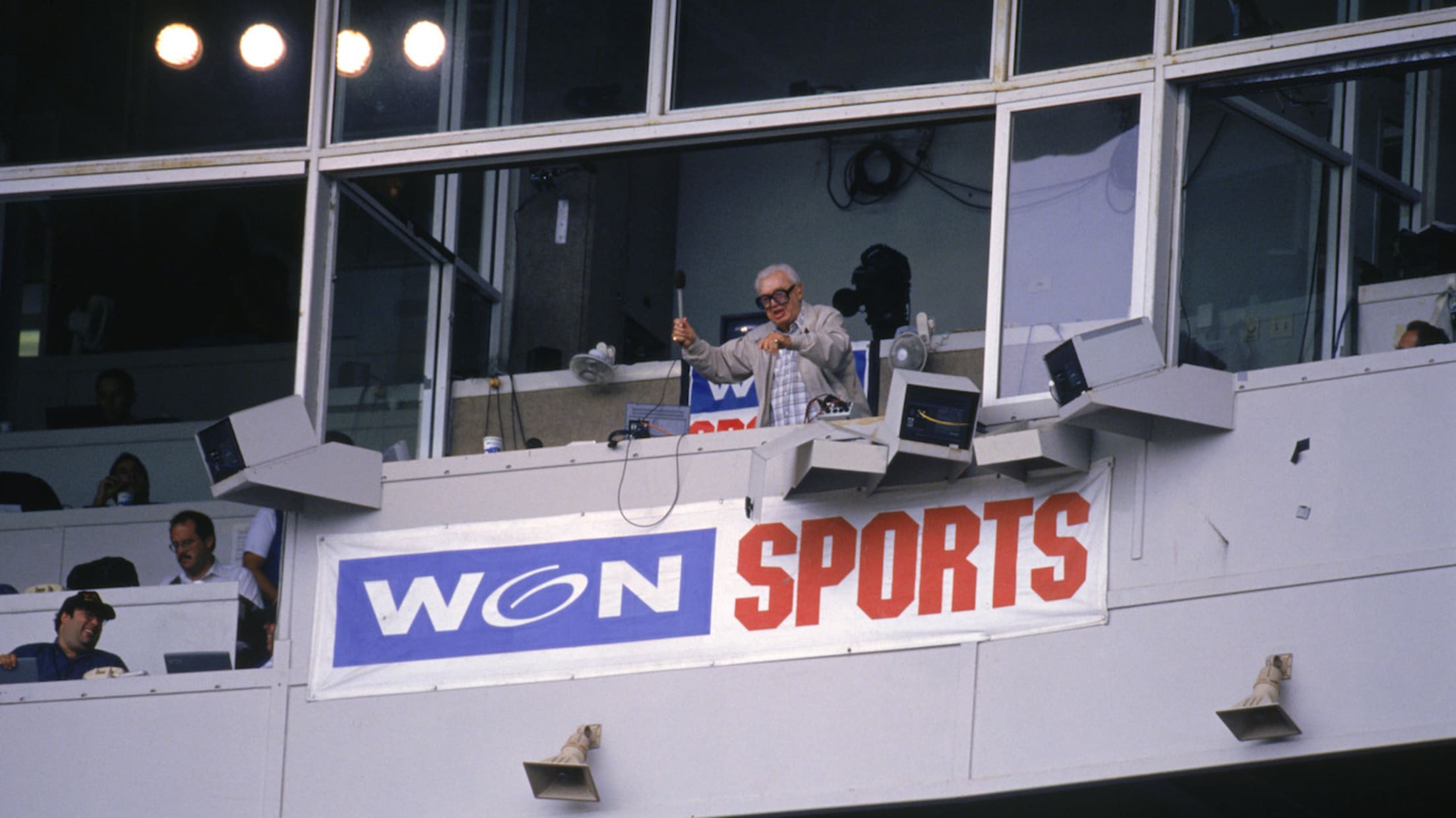

The Orioles play John Denver. The Mets use "Lazy Mary". The Cubs hand the mic over to all kinds of famous faces, with varying results. But while every team has put its own stamp on the stretch, no one can agree on how the thing got started in the first place.

The most popular theory involves William Howard Taft, 10th Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, 27th president of the United States and bonafide baseball revolutionary. On April 14, 1910, Taft was enjoying the hometown Washington Senators' Opening Day contest against the Philadelphia Athletics -- the very same game at which he threw baseball's first presidential first pitch. There was just one problem: At a reported 6-foot-2 and well over 300 pounds, Taft was a rather large man, and after a while, the rigid wooden seats at Washington's Griffith Stadium took their toll on him.

So, after the top half of the seventh, Taft stood up to stretch his legs -- and, not wanting to be disrespectful of the highest office in the land, everybody else in attendance did, too. The Senators went on to win that day, the stretch soon became common practice and the rest is history. At least, that's how the legend goes.

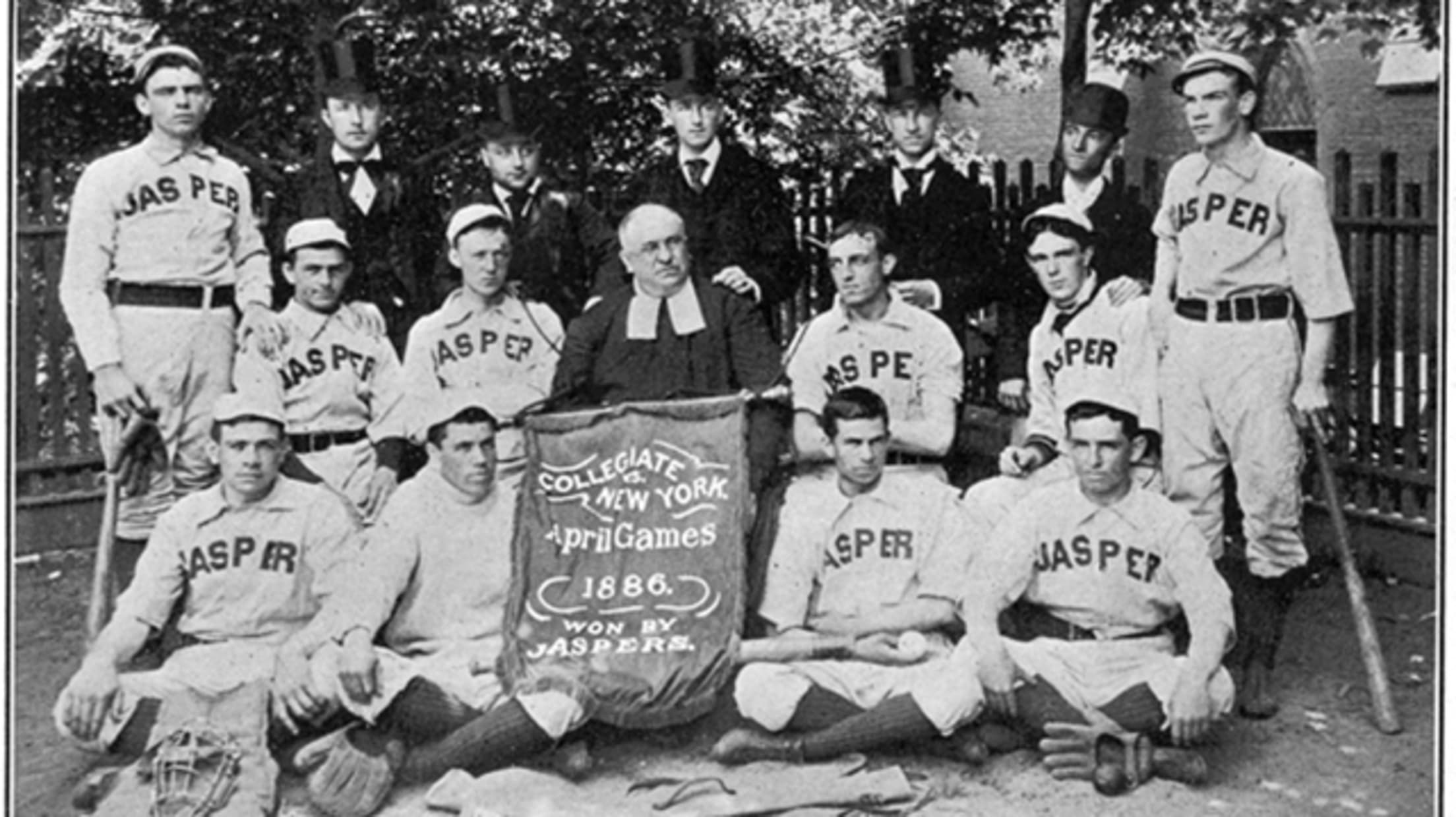

Unfortunately for Taft, though, there's another origin story that far predates his trip to the ballpark. In the early 1880s, Brother Jasper Brennan brought the relatively unknown game of baseball to Manhattan College. As both the school's Prefect of Discipline and the team's manager, it was Brennan's responsibility to look after both the players on the field and the students in the stands -- the latter of whom weren't allowed to move or leave their seats until the game was over.

During a game against the semi-pro New York Metropolitans in June of 1882, however, Brother Jasper's conduct policy became untenable. It was a very hot day, and the students became restless after an hour or two in the sun. So, Brennan came up with a compromise: Before the bottom of the seventh, he called timeout and allowed the students to get up and stretch for a few minutes.

This quick break soon became standard at every Manhattan home game, and when New York Giants fans saw it for themselves during an exhibition game between the two teams, they liked the tradition so much that they brought it to the Polo Grounds. To this day, Manhattan proudly claims that it was the birthplace of the seventh-inning stretch -- at an alumni dinner in the 1980s, all members rose and stood in honor of the occasion's 100th anniversary -- and the timeframe does seem to match up. As an 1883 article in "The Sporting Life" noted:

"In most of the large cities, there is a peculiar practice in vogue at baseball games. At the end of every few innings, some tired spectator, who has been wrestling with the hard side of a rough board seat, gets up and yells 'Stretch!' A second after, the entire crowd will be going through all the movements of a stretch."

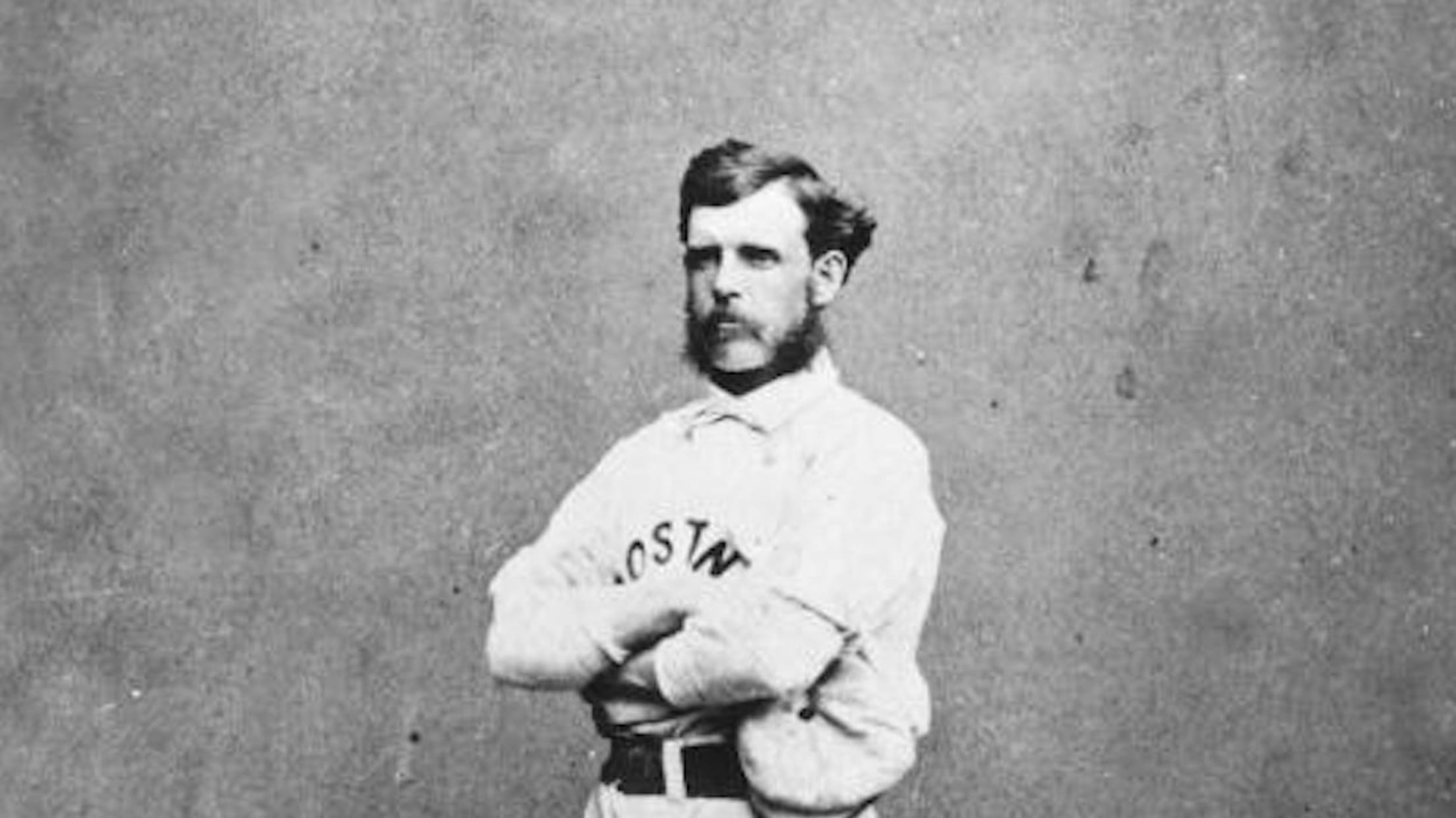

Unfortunately, even that version of events doesn't seem to be quite true. In 1982, Cincinnati Magazine dug up a letter written in 1869 -- 13 years before Jasper's innovation -- by Harry Wright, original Cincinnati Reds organizer, founding father of professional baseball and extremely dapper gent:

In it, Wright describes how Reds fans "all arise between halves of the seventh inning, extend their legs and arms, and sometimes walk about. In so doing they enjoy the relief afforded by relaxation from a long posture upon hard benches." So, it sure seems like the seventh-inning stretch goes at least as far back as the late 1860s, and we may never know for sure whose idea it was. Whoever they are, though, we are forever grateful: