Let us tell you about the craziest free-agent saga in baseball history

MLB has seen some downright wild free agency roller coasters in its history, from Catfish Hunter's 30-team bidding war to Alex Rodriguez's $252 million game-changer to Greg Maddux rebuffing a full-court press from George Steinbrenner because the Braves "offered him the most substantial degree of assurity of taking the World Series" (no, really).

But in decades of dramatic deals, only one has featured fistfights, cash flying under the table and a hearing in front of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania -- so pull up a chair and discover how Nap Lajoie (very briefly) became a Philadelphia Athletic in the craziest free agent story in baseball history.

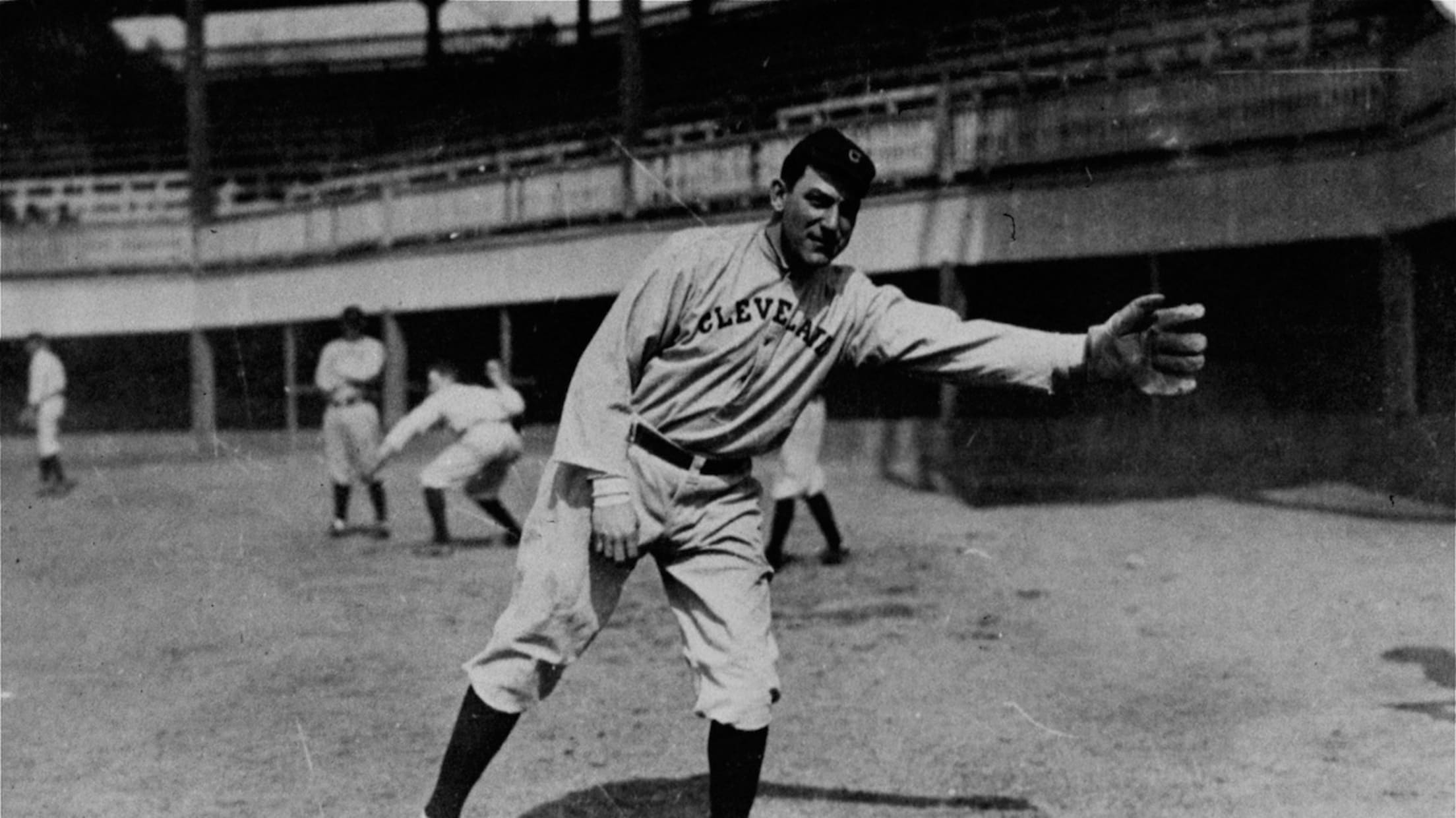

Lajoie (pronounced Lah-ZHWA) was destined for stardom pretty much from the moment he picked up a bat. He was a star growing up in the late 19th century in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, where he served as a part-time ringer for local semipro teams. He was a star in the Minor Leagues, even while driving for a livery service and earning one of the best nicknames in baseball history: The Slugging Cabby. And, after the Phillies made his team an offer they couldn't refuse -- a then-unheard of $1,500, about $46,000 in today's dollars -- Lajoie immediately set about becoming a star in the Show.

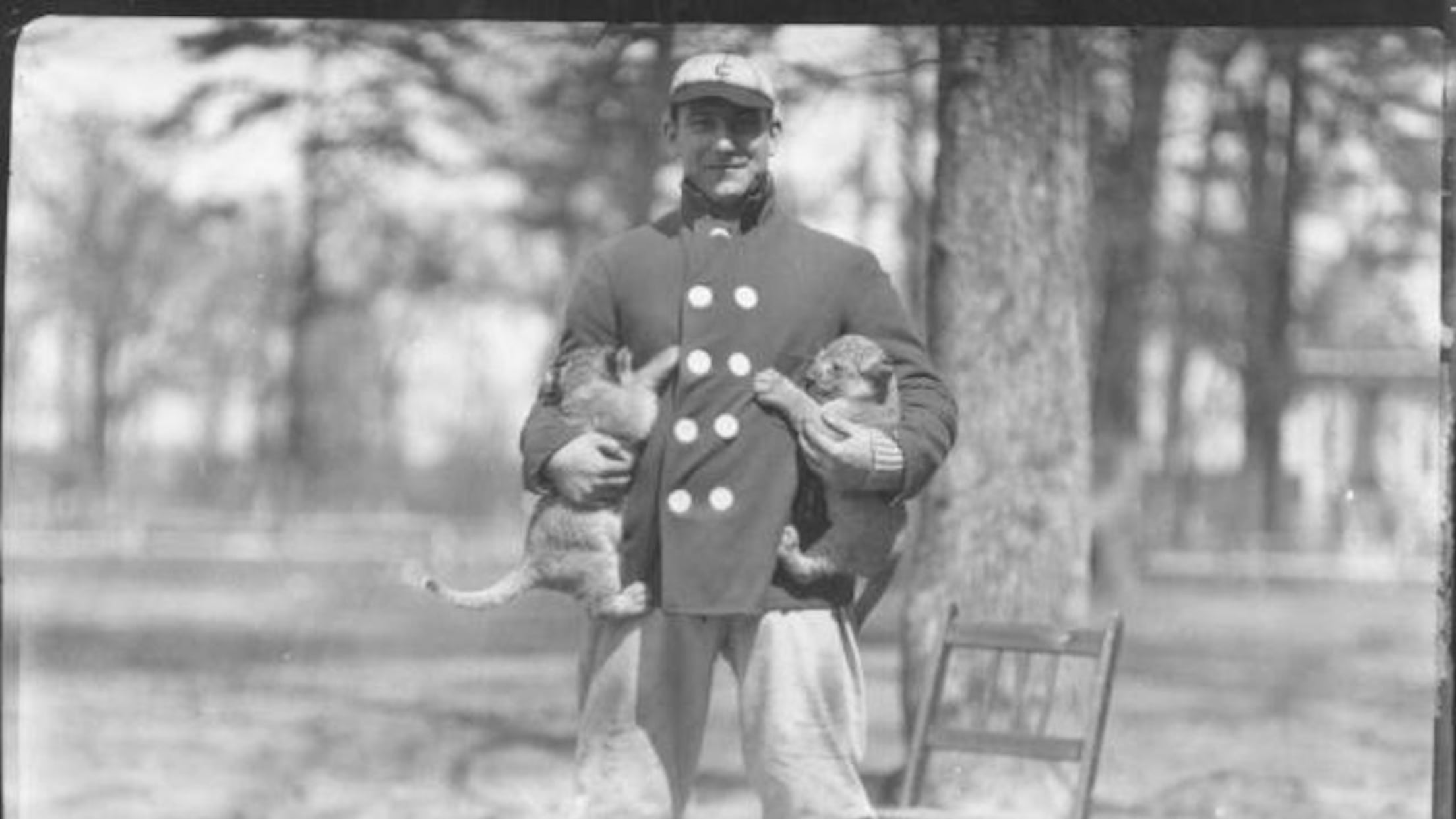

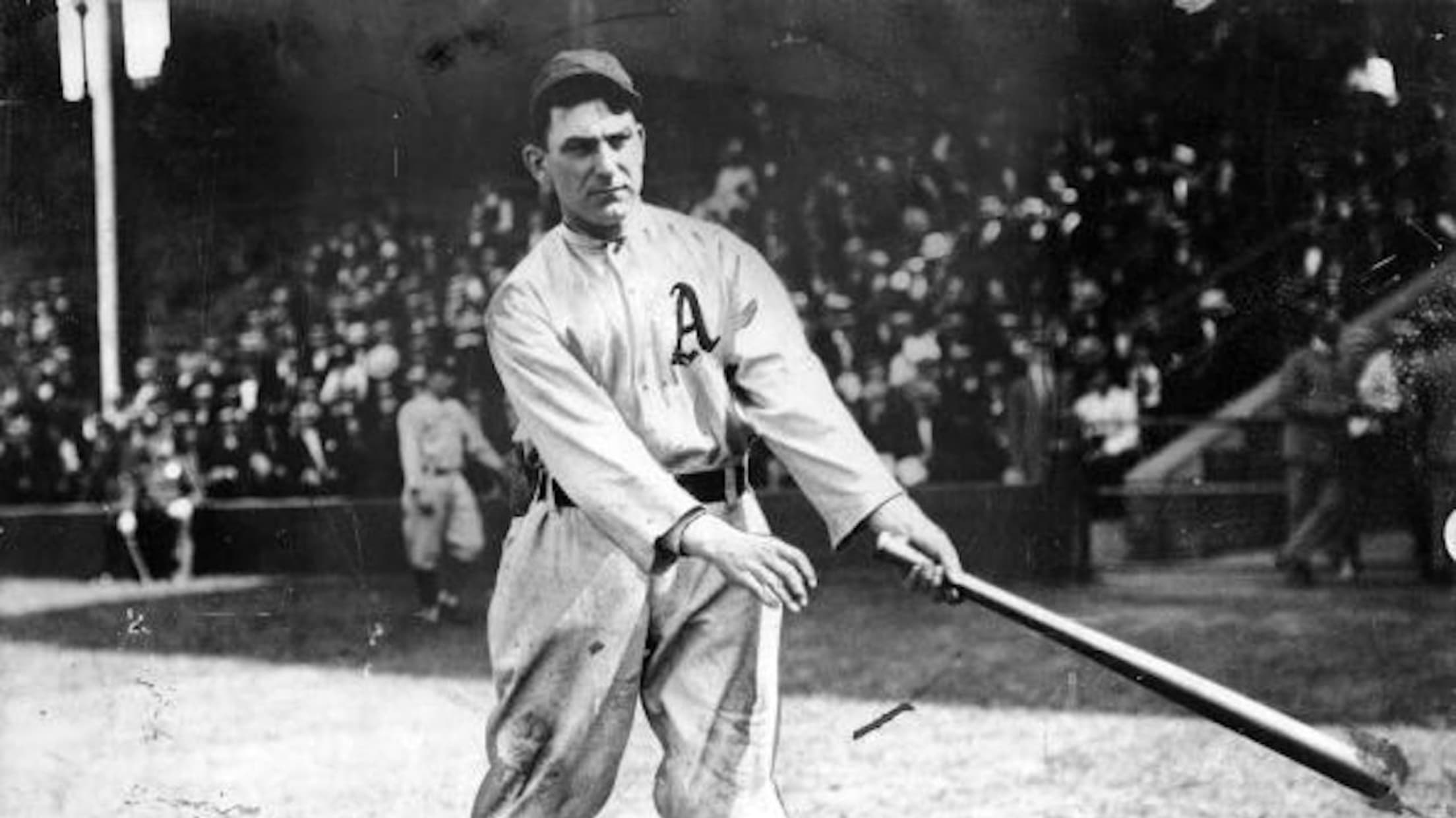

He took the Majors by storm in 1897, leading the league in slugging and total bases in his first full season. By the turn of the century, he'd established himself as the best second baseman in baseball and one of its brightest young stars. He just looked like the broad-shouldered superhero you'd want to build a team around -- the kind of guy who would, say, casually hold two lion cubs in his hands just for fun:

Of course, as one of the brightest young stars in the sport, he also expected to be paid like one -- and that's where things went off the rails.

At the time, National League players weren't allowed to earn more than $2,400 a year. Owners took this as more of a guideline than a rule, though, and routinely supplemented their stars' salaries with cash under the table. Lajoie was no different: Each year, Phillies boss John Rogers slipped him an extra $200. Which was all well and good ... until Lajoie discovered that roommate and fellow star Ed Delahanty got $600.

Befitting a man who once had to be physically removed from the ballpark by police following an ejection, Nap was not pleased. He demanded that Rogers make up the difference. Rogers refused, and while it didn't affect Lajoie on the field -- he hit a very Lajoie-like .337/.362/.510 in 1900 -- his relationship with the Phillies was irreparably broken. By all accounts, he spent that year furious at everyone and everything associated with the team: At one point he even got into a full-on fistfight with right fielder Elmer Flick, ostensibly over who owned a certain bat in the clubhouse. (The fight ended when Lajoie threw a punch, missed and broke his thumb on a grate.)

By the end of the season, Lajoie still hadn't gotten his raise. But what could he do? The NL was by far the biggest game in town -- with the best players and the best pay and the most fans. Besides, the phrase "free agency" didn't even exist yet; even if Lajoie wanted to jump ship, his hands were tied. Until he decided to go nuclear, that is.

Originally an association of Minor League teams, the Western League had rebranded in 1900 as the American League, looking to offer a serious challenge to the NL's dominance over pro baseball in America. But they faced an uphill climb, both financially and in the minds of fans. What they needed was a splash, something or someone that would grab people's attention and force them to take the AL seriously -- someone like, say, Nap Lajoie.

At the urging of AL president Ban Johnson, the newly formed Philadelphia A's approached Lajoie with an offer: a staggering $24,000 over four years, more money than any NL player could ever dream of. Lajoie understandably said yes, and in 1901, he won AL's Triple Crown -- more than doubling the A's attendance in the process.

Rogers wasn't about to take the loss of his star to a crosstown rival lying down, though. He filed a lawsuit, and the case eventually rose all the way to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court -- which delivered what appeared to be a crushing blow to Lajoie and the AL. The court upheld the reserve clause in Lajoie's contract and barred him from playing for any team other than the Phillies.

But an AL lawyer had found a loophole: It turned out that the court's injunction was only valid in Pennsylvania, meaning that Lajoie was free to jump ship -- provided that he did it somewhere else. The A's quickly traded Lajoie to the Cleveland Bronchos, and he simply didn't travel with the team whenever it had to play in Philly. (Avoiding the league's best hitter might explain why that year's A's still boast the second-largest home/road record differential in baseball history.)

Lajoie starred in Cleveland for the next 13 years, becoming so synonymous with the franchise that they adopted the nickname Naps until he retired -- at which point a group of local sportswriters rechristened the team the Indians. Some 20 years later, Lajoie was enshrined in Cooperstown as part of the first Baseball Hall of Fame class ever.

That's him in the top row third in from the right, above Connie Mack.