Why Mariano Rivera was the heart and soul of the Yankees' '90s dynasty

I'll admit that I was as guilty as anyone. I'd rehearse the jump throw in the backyard until my dad practically dragged me in for dinner. I held on to the Sports Illustrated cover -- "Good field, good hit, good guy" -- for years. I didn't show up for my first season of Little League for the chance to play baseball so much as the chance to wear a No. 2 jersey (I didn't get it, but I did snag No. 12).

If you were kid in the tri-state area in the late '90s, there's a good chance that your world revolved around Derek Jeter. I'm not here to poke a hole in that -- because really, how could it _not_?

Even now, that unofficial hierarchy remains more or less intact. The famous Core Four all got their Monument Park moment, but it was Jeter who inspired the emotional farewell ads and Jeter whose number retirement ceremony brought all the stars to the Bronx.

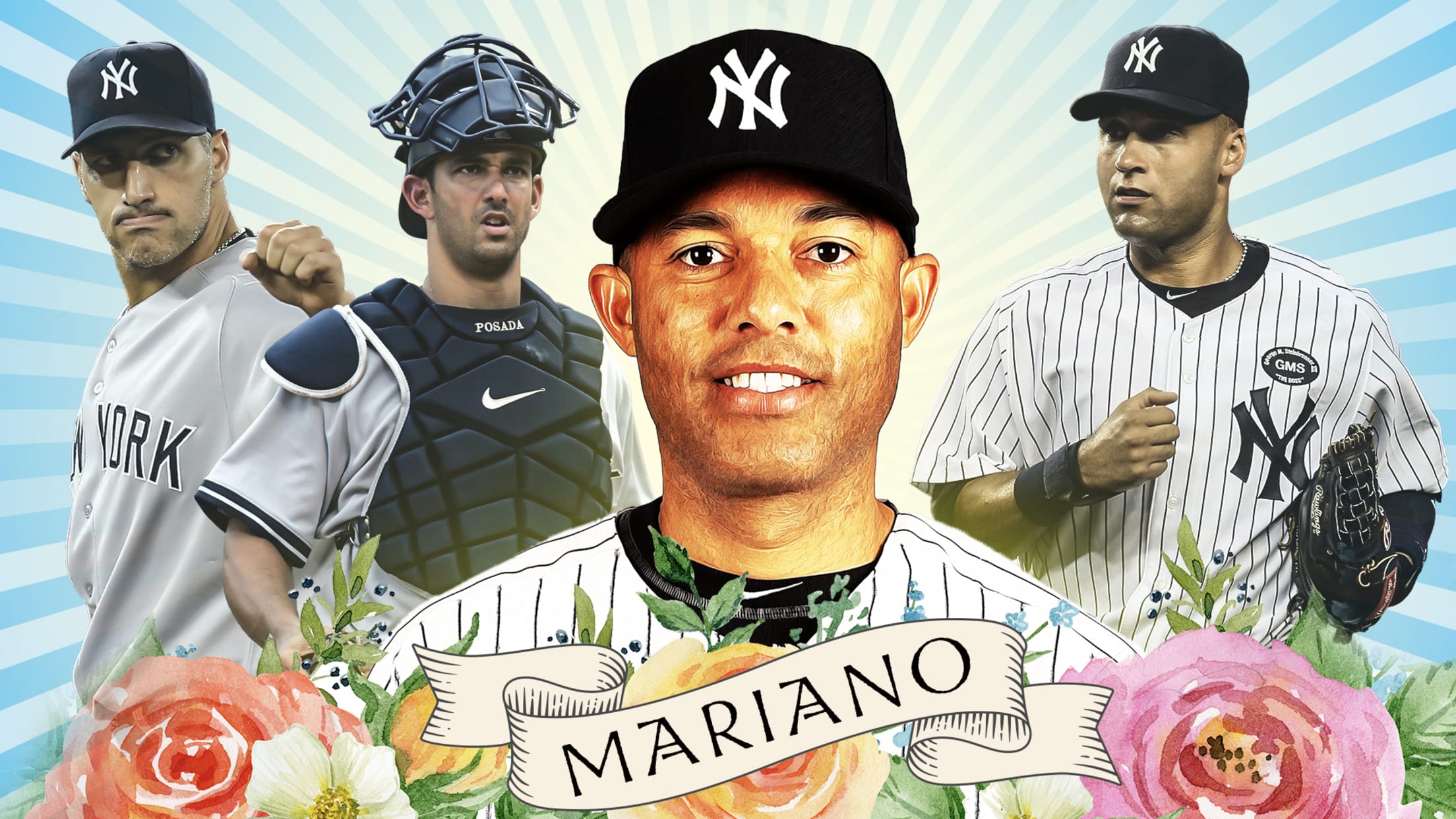

But as the Baseball Hall of Fame gets set to induct the class of 2019 on Sunday, I've found myself thinking back to those Yankees teams, and the things that stuck with me the most as a fan of them. (Aside from the rings, of course.) While Jeter's career hasn't gotten less impressive with hindsight, I would like to submit the following: Derek Jeter was the face of New York's dynasty, but Mariano Rivera was its heart and soul.

Aaron Boone takes Tim Wakefield deep in the 11th inning of Game 7 of the 2003 ALCS, sending New York on to the World Series after one of the most stunning rallies in sports history. It's still probably the apex of my childhood as a Yankees fan.

But my most memorable image from that night didn't come from Boone or Jeter or Pedro sitting shell-shocked in the dugout. It came from the pitcher's mound, celebration raging all around, captured almost as an afterthought as Boone rounded the bases:

The man crumpled in the middle of the diamond, looking like his spirit had just left his body, was Rivera. After New York stormed back to tie the game, Joe Torre went to his closer to start the top of the ninth. Mo responded with three scoreless innings -- and you got the feeling that, if Boone hadn't gone yard, he would've kept going until his arm fell off or somebody scored, whichever came first. He'd poured everything he had into that moment, and when it was over, all he had it in him to do was walk out to the mound, collapse and cry. Eventually, after the bedlam had subsided a bit, his teammates carried him off the field on their shoulders.

Rivera never had the magnetism to capture New York's imagination. He was unfailingly polite but never offered more than that. This was how he dressed in his early 20s. He even managed to pour cold water on the single coolest thing about him: When asked about his "Enter Sandman" entrance, Mo said that he was glad that fans enjoyed it but that "I don't listen to that kind of music." It's OK to admit it: The man was a bit boring.

But he was also the embodiment of everything that we loved about those teams and about the franchise itself. For fans of the Bombers, the Yankees aren't just good: The Yankees are inevitable, the Evil Empire. A lot of great teams made a run at the crown in those years, and nearly all of them watched the dream slowly wither away.

Jeter brought the fireworks, but that sinking feeling that opponents felt at the end of a game? That was Rivera. The man was a metronome -- in his 18 years as a full-time reliever, he posted an ERA above 2.50 exactly twice, while posting an ERA under 2.00 11 times. He was inarguably the best at what he did, and he seemingly carried that fact as casually as he breathed, no matter how pressure-packed the moment or how raucous the crowd. Mo simply strode to the mound and sucked the life out of the building. Even the way he went about it was pitch-perfect: He didn't throw 98, he didn't rack up strikeouts; you knew the cutter was coming, and all you were left with was the knob of a shattered bat in your hand and a slow dribbler to second base to end the game.

I think that's why the rare moments when he faltered hurt so much, and why I'll never forgive Bill Selby until the day I die.

Yes, Rivera only threw an inning or two at a time. Yes, there were more valuable members of each championship team. But when he accepts his rightful place in Cooperstown this weekend, I'm going to remember celebrating in my living room, Mo on the mound in the middle of another dogpile, and how I wouldn't have had it any other way.