Meet four little-known figures who tell the story of early Japanese American baseball

Baseball first came to Japan in 1872, with an American professor named Horace Wilson. He'd been hired by the Japanese government to help modernize the country's education system, and while teaching English at Kaisei Gakko (the forerunner to today's Tokyo University), he decided his students needed a little more physical exercise. He taught his students America's pastime, and soon other American teachers were organizing baseball games as well.

The game rapidly gained popularity among adults thanks in part to Hiraoka Hiroshi, who studied in New York City and brought his love for America's pastime back with him. He was a Red Sox fan who missed seeing professional teams so much that he organized Japan's first -- the Shinbashi Athletic Club Athletics. Japanese immigrants who came to the US in the early 20th century were already familiar with baseball, and they wasted no time in forming teams of their own.

But before Jackie Robinson broke MLB's color line in 1947, Japanese Americans couldn't play in the Major Leagues. That meant that Japanese immigrants and their American-born children started their own teams and competed for their own championships. The Issei and Nisei Leagues were just as vibrant as other outsider baseball communities, but fewer records of them exist. So, who were some of the athletes, umps and boosters involved? Let's meet a few foundational figures now.

But first, a guide to Japanese American generational terminology

Issei: First generation, born in Japan, emigrated to another country

Nisei: Second generation, born outside of Japan to at least one Issei parent

Sansei: Third generation, born outside of Japan to at least one Nisei parent

(You'll want to know this to clarify some things throughout the post.)

Shohei "Frank" Tsuyuki

Issei teams formed in California as early as 1903, taking on community teams from all over the Bay Area. Frank Tsuyuki helped found a team called the KDC, which stood for Kanagawa-ken Doshi Club. A rough translation of the name: A bunch of guys from Kanagawa … Club. It was the second all-Issei team in the United States.

But in the early days, actually playing the game was fraught. Here's an excerpt from Kerry Yo Nakagawa's "Japanese American Baseball in California."

Larry Tsuyuki would remember his dad telling him, "A lot of these white teams didn't take losing very well. As the game got closer to the end and we were winning, we would start gathering up our equipment, and as soon as the game ended, we would grab our gear and run."

After the Great Depression, Tsuyuki and his family ended up in Monterey County. He had aged out of playing himself, but he became an umpire for the Nisei Leagues that were beginning to emerge along the West Coast.

Setsuo and George Aratani

By the 1920s and '30s, any Japanese American community with nine people who could play ball found themselves with a team. The Northern California Japanese Baseball league fielded eight semi-pro teams, and the Central Valley Independent League had 10 (including the delightfully-named Watsonville Apple Giants). The Nisei Athletic Club played in Hood River, Ore., against white pick-up teams.

Setsuo Aratani played for the Fuji Athletic Club in his youth, the first Issei team in history. By the mid-'20s, he'd left and become a successful lettuce farmer in Guadaloupe, Calif. But he didn't want to give up the sport he loved, so he started a company team.

Two of his employees scouted the rest of their coworkers, and they assembled a multi-ethnic squad. In 1927, Aratani paid for his team, the Guadaloupe Packers, to go on a 15-day goodwill voyage to Japan. He brought along his 10-year-old son, George, and let him pinch-hit in one of the games.

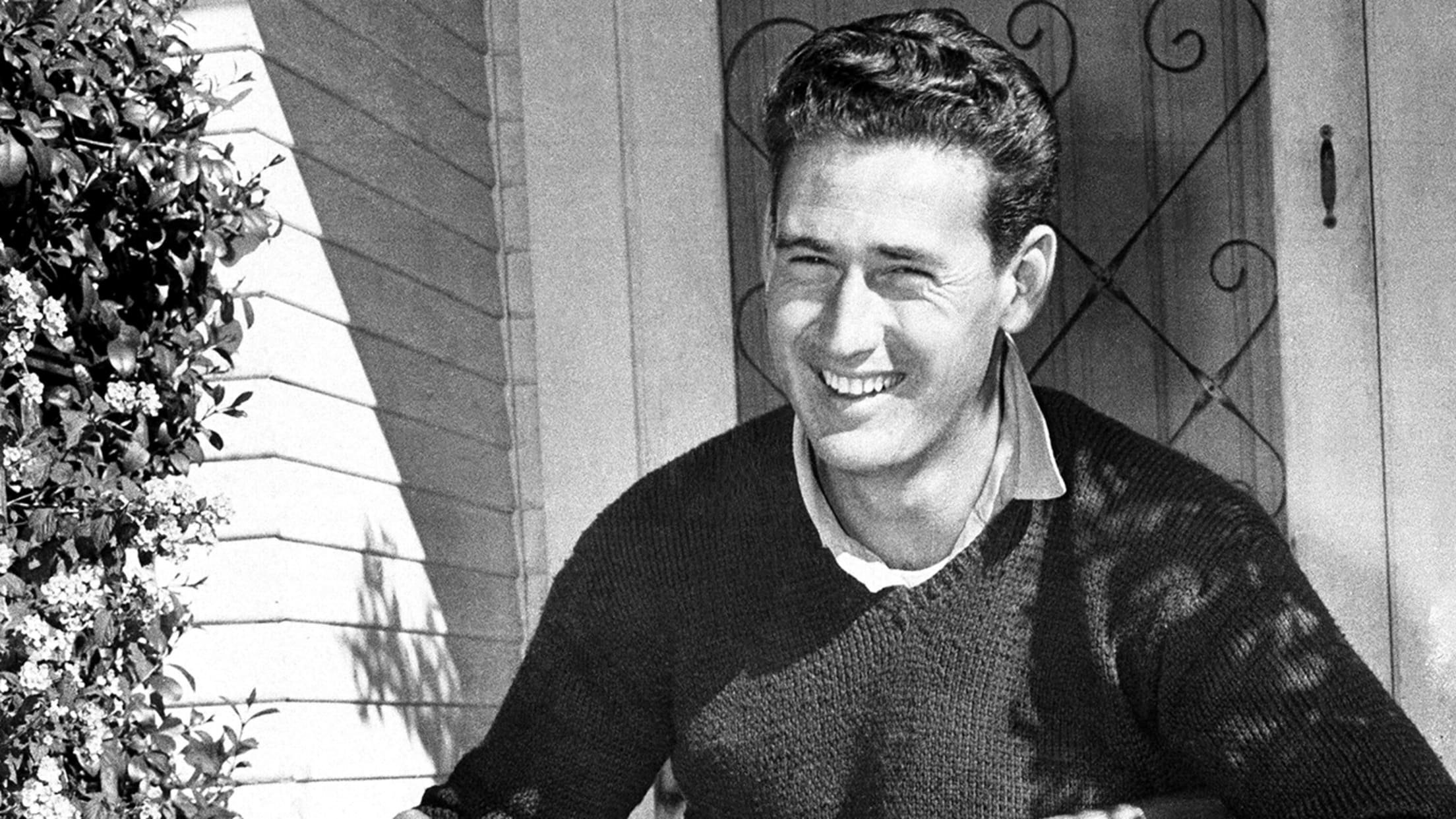

All of that early athletic experience seems to have done him good. As a freshman at Santa Maria High School, he was already a shortstop on the varsity team. In 1932, George's team faced off against Hoover High School for the state championship title. Let's see if you can name the following Hoover High alumnus who also happened to play in that game:

Yes, that's Ted Williams.

In "Japanese American Baseball," George described Williams as "lanky and kind of uncoordinated." In that championship game, The Splendid Splinter struck out three times. Santa Maria won the championship, and the pitcher who struck out Williams, Lester Webber, was drafted by the Dodgers. George was scouted by the Pirates, and he even worked with Honus Wagner at the Bucs' Spring Training -- but he was never signed. After playing ball at Keio University in Japan, he went on to become the founder of Mikasa china and owner of Kenwood Electronics.

Alice Hinaga

Alice Hinaga had three brothers, and they were all ballplayers. Russell and Chickie played for the San Jose Asahi as pitcher and shortstop, respectively. In 1935, Russell even pitched his team to a win over the visiting Tokyo Giants. George, another Hinaga brother, played a year of semi-pro ball with the Vancouver Asahi.

But it was Alice who was a sought-after starting pitcher and cleanup hitter. She once threw a 14-K game against the Pacific Telephone Girls in 1933 and was just one of two Nisei women to play in the Women's Night Ball Association of San Jose. From "Japanese American Baseball," again:

Growing up, I would always tag along with my brothers, who played baseball every chance they could get. I guess I got pretty good at being with them all the time … At that time there were no Japanese female baseball teams, so played with the white American girls. I was the American version of … Hideo Nomo because I was the only Nisei."

Kenichi Zenimura

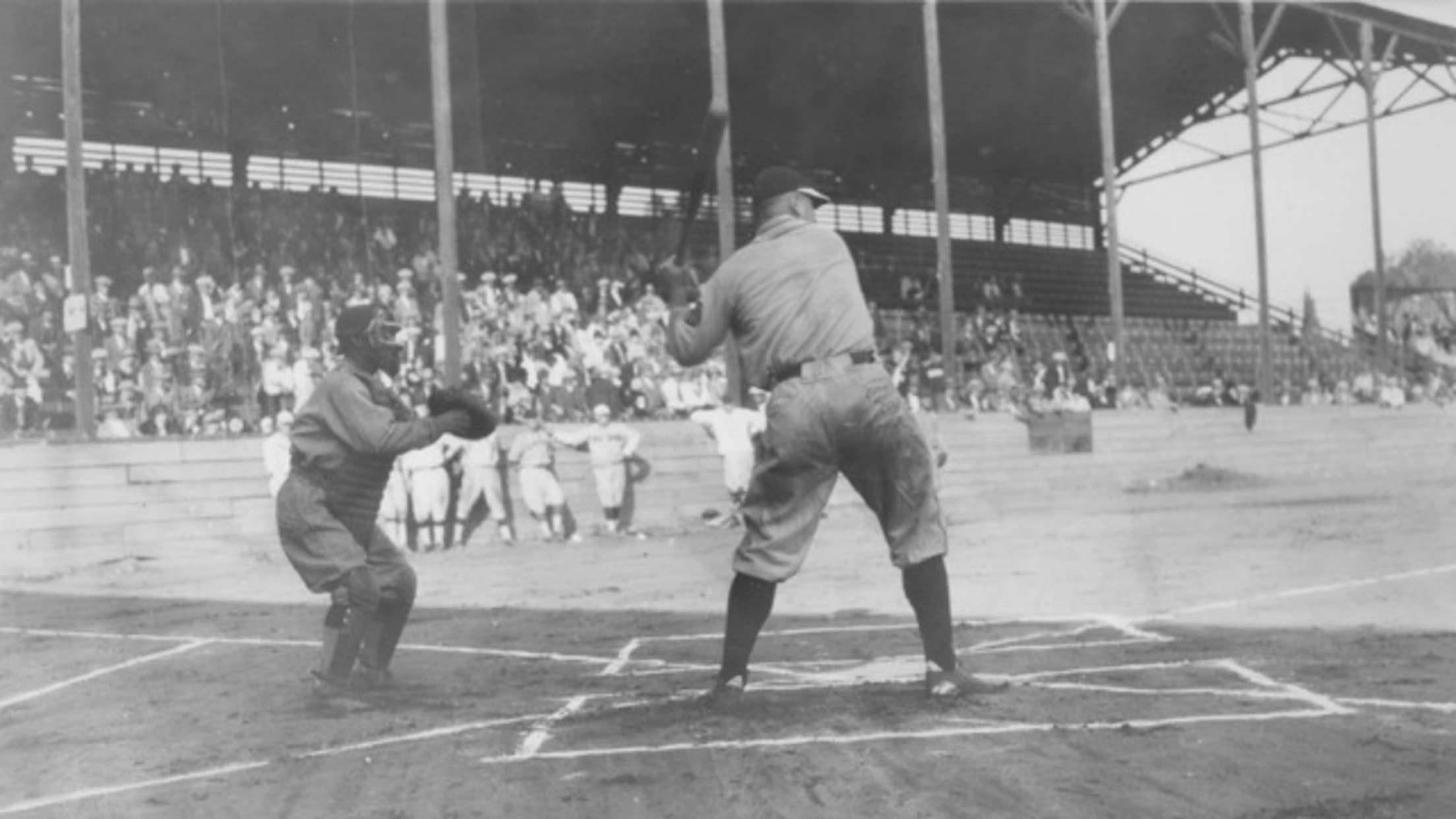

They called Kenichi Zenimura the "Dean of the Diamond," and he truly presided over baseball at every level. He played all nine positions and put together barnstorming tours with MLB superstars. Here he is behind the plate. That guy at the plate? Lou Gehrig:

Zenimura also brought baseball to one of the most inhospitable places imaginable: an internment camp.

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942, hundreds of thousands of people of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast were uprooted from their homes and interned in camps in the west, Zenimura among them. Before WWII, he played for the Fresno Athletic Club, but following the order, most of his teammates were sent to a camp in Jerome, Ark. He was separated from them, and ended up in Gila River, Ariz.

Zenimura had already built one ballpark in Fresno, where he'd hosted contests against West Coast Negro League teams and the Pacific Coast League's Salt Lake City Bees, so why not just build another one? He and his sons cleared the ground, and as soon as fellow internees realized what they were doing, they pitched in.

… the internees diverted water from a nearby irrigation ditch and flooded the infield to harden and pack it down. Then they took a three-hundred-foot water line from the laundry room and made a spigot at the back end of the pitcher's mound so that they could have Bermuda grass in the infield and outfield. A castor-bean home run fence was grown, which reached eight to ten feet in height.

Under the cover of night, Zenimura focused on the next step -- building a grandstand. Said one of Zenimura's sons, Harvey:

"We were in Block 28, and the lumberyard was way across the other side of the camp, probably another mile away. We'd go out there in the middle of the night and get lumber and lug it all the way out into the sagebrush, bury it in the desert and then go back later and get it as we needed it. The camp officials probably knew what was going on but nobody said anything."

It's also the ballpark where actor Pat Morita (you know him from the Karate Kid movies) learned to love baseball. He and his family were also interned at Gila River, and it was the first place he saw a live ball game.

After internment, Zenimura coached baseball in Japan and the U.S., and eventually earned the nickname "The Father of Japanese American Baseball." Unfortunately, neither Zenimura or his Nisei League teammates ever made it to the Show. It would take until 1975, when the Cardinals called up Sansei pitcher Ryan Kurosaki, for a Japanese American player to crack the big leagues.

Nisei League photos courtesy of Kerry Yo Nakagawa and the Nisei Baseball Research Project.