100 years ago, Babe Ruth became Babe Ruth with a 500-foot homer into an Alligator Farm

It's a question you've probably always wanted to know: When did Babe Ruth become Babe Ruth? How did the ace pitcher transform into the prodigious slugger? At what point did the kid from the Pigtown section of Baltimore turn into the Great Bambino -- the mythical batsman, the most famous ballplayer who ever lived?

Well, many point to a Spring Training game nearly 100 years ago. A time when there were no Cactus or Grapefruit Leagues, but just one preseason baseball mecca in Hot Springs, Ark. More than 130 future Hall of Famers trained in the area during the late-1800s into the early 20th century -- including names like Cy Young, Cap Anson, Walter Johnson, Mel Ott, Ty Cobb and Ruth. Like the other players, Ruth hiked the mountains, frequented the restaurants and bathed in the Hot Springs -- becoming an annual man about town. He worked hard, but, being the Babe, he also had a lot of fun. I mean, look at this photo.

Ruth, entering his fifth MLB season in 1918, was mostly a full-time pitcher. He had nine homers in 407 plate appearances and a fantastic 67-34 record, while maintaining a 2.07 ERA. In 1916, he went 23-12 with a 1.75 ERA, nine shutouts and gave up zero home runs in 323 2/3 innings pitched. He was a rising 22-year-old star, one of the best hurlers in the Majors.

But Boston knew it couldn't keep his bat out of the lineup and, after many players left to serve in World War I, management decided to try Ruth out at first base that March. Ruth reported to Arkansas for the Boston Red Sox in, as we might say today about every single player who ever loses weight during the winter, the best shape of his life. Not from doing giant box-jumps or balancing on skateboards, but for a much more early-20th century reason: He needed to chop wood all winter to heat his Massachusetts cottage.

The Red Sox's regular first baseman, Dick Hoblitzel, was also late to camp, so, manager Ed Barrow really had no other choice but to play the Babe in the field. The 6-foot-2 behemoth of a man, who towered over most other players around him, took advantage of his manager's move in that very first exhibition game at Whittington Park against the Brooklyn Dodgers on March 17. In the fourth inning, he hit a long drive beyond the outfielders' heads and into a woodpile -- circling the bases for a homer. Then, in the sixth, he hit the famed dinger that turned him from simple human into home run god.

The ball sailed over the right-field fence, across the street and landed in an alligator farm. Fans for both teams stood up and cheered -- astounded by how far the homer traveled. The Boston Globe had this to say postgame:

…the other (homer #2) not only scaled the right-field barrier, but continued on to the alligator farm, the intrusion kicking up no end of commotion among the "Gators."

And from the Boston Post:

"... he drove the ball so far over the right field fence for a second circuit clout that even the players of the Brooklyn team themselves had to arise to the occasion and cheer."

While most spectators at the time figured it to be the longest home run they've ever seen hit, how far did it really go?

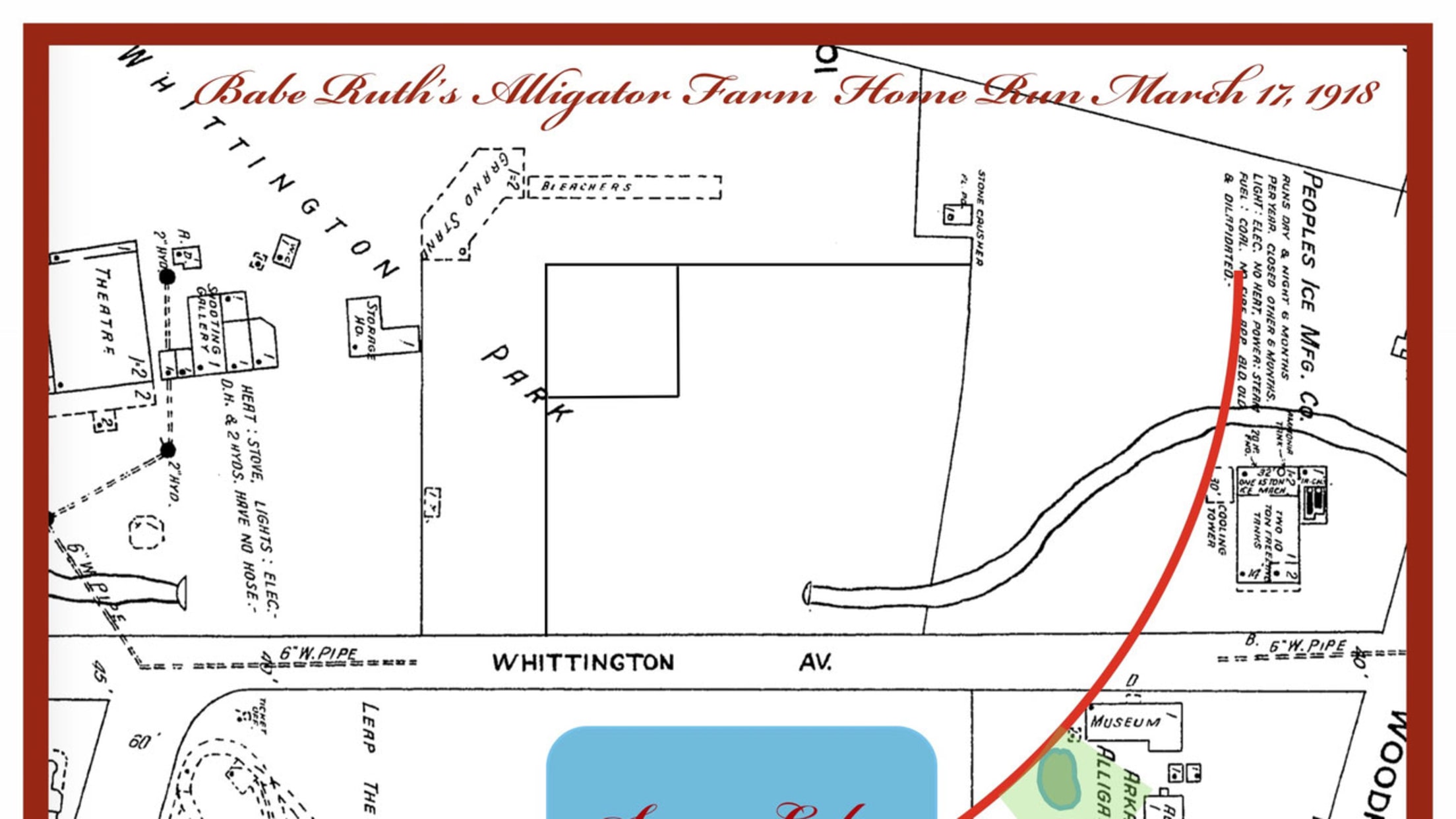

Well, in 2011, Hot Springs baseball historian Bill Jenkinson and CEO of the Convention and Visitors Bureau Steve Arrison hired an engineering crew to measure the distance from where the Whittington Park home plate once stood (now a parking lot) out to the still-existing alligator farm. Using old photographs, modern satellite imagery and tree markers, the ball was determined to have traveled at least 500 feet. Here's a sketch of what the homer's route looked like -- the green box signaling the landing spot:

And, as Jenkinson meticulously writes, there is a case to make that the blast was the first in baseball history to reach the 500-foot mark. Pre-Ruth sluggers like Roger Connor and Dan Brouthers probably hit balls upwards of 450 feet, but there's not much mention of those mammoth homers -- mostly because it was just so long ago and power wasn't a major factor in the game. Offense picked up in 1911 when a cork was first inserted inside a baseball. This helped batters like Ruth (and let's be honest, there weren't many others like him at the time) crush baseballs longer than ever before dreamed.

Weirdly enough, or, perhaps not that weird considering who we're talking about, Ruth hit a dinger estimated to be even longer the following week at Whittington Park. The Boston Post claimed it cleared the fence by 200 feet and soared over Swan Lake (in the above diagram). Ruth went on to get more at-bats than ever during the regular season -- leading all of baseball with 11 long balls. He hit 29 the next year and 54 the next. His career as a full-time starting pitcher was all but finished, supplanted by his herculean abilities at the plate -- much of which can be attributed to those few days at a little ballpark in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

In the midst of his March 1918 barrage, Ruth probably put it best when Boston's owner told him how much money he owed in missing balls.

"I can't help it. They ought to make these [expletive] parks bigger."