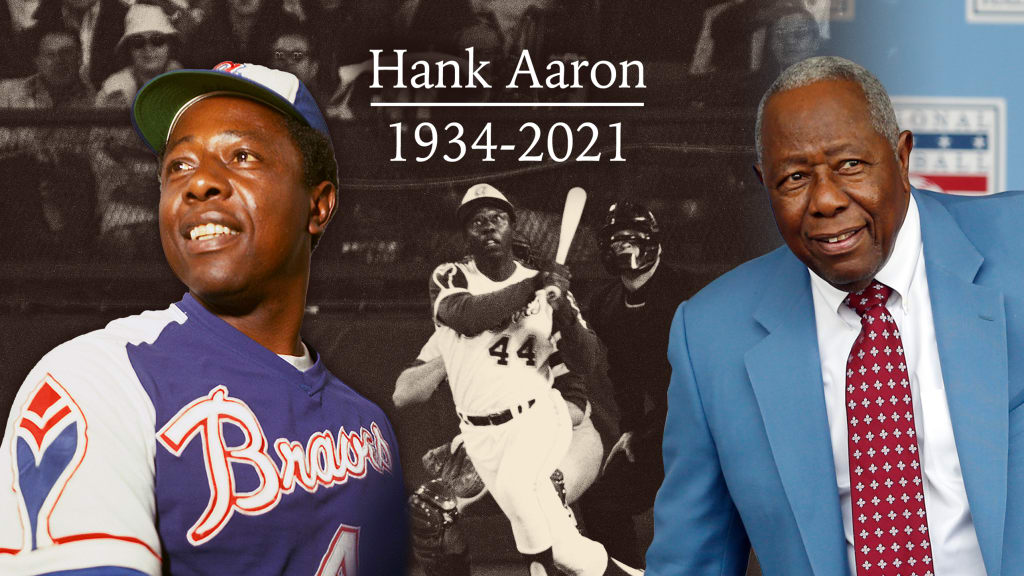

Baseball legend Hank Aaron dies at 86

Hank Aaron, a son of the Deep South who soared above its poverty and racism to become one of the most consequential figures in American history, died Friday at age 86.

His death prompted an outpouring of tributes from those who’d known him personally or simply been inspired by a remarkable life lived with relentless dignity and grace in the face of a seemingly endless fountain of hate during his pursuit of a sacred baseball record -- 714 home runs -- held by a white icon, Babe Ruth.

“Hank Aaron is near the top of everyone’s list of all-time great players. His monumental achievements as a player were surpassed only by his dignity and integrity as a person. Hank symbolized the very best of our game, and his all-around excellence provided Americans and fans across the world with an example to which to aspire. His career demonstrates that a person who goes to work with humility every day can hammer his way into history -- and find a way to shine like no other," Commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement.

“Hank eagerly supported our efforts to celebrate the game’s best and to find its next generation of stars, including through the Hank Aaron Award, which recognizes offensive excellence by Major League players, and the Hank Aaron Invitational, which provides exposure to elite young players. He became a close friend to me in recent years as result of his annual visit to the World Series. That friendship is one of the greatest honors of my life. I am forever grateful for Hank’s impact on our sport and the society it represents, and he will always occupy a special place in the history of our game. On behalf of Major League Baseball, I extend my deepest condolences to Hank’s wife, Billye, their family, the fans of Atlanta and Milwaukee, and the millions of admirers earned by one of the pillars of our game.”

Aaron passed Ruth on the all-time home run list on April 8, 1974, at age 40, and then played parts of two more seasons to put the finishing touches on a Major League career that spanned 23 seasons, from his debut as a 20-year-old for the Milwaukee Braves in 1954 to his retirement in 1976 as a 25-time All-Star, National League Most Valuable Player (1957) and two-time batting champion. He hit .393 when the Braves won a seven-game World Series against the Yankees in 1957. He was baseball's home run king for 33 years.

He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982 after being named on 97.8 percent of ballots. At the time, only Ty Cobb, with 98.2 percent in 1936, had received a higher percentage of votes from the baseball writers.

Aaron received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2002, and long after he’d played his final game, remained an outspoken advocate of civil rights, telling his own story eloquently, and at times, bluntly.

“We are absolutely devastated by the passing of our beloved Hank. He was a beacon for our organization first as a player, then with player development, and always with our community efforts. His incredible talent and resolve helped him achieve the highest accomplishments, yet he never lost his humble nature. Henry Louis Aaron wasn’t just our icon, but one across Major League Baseball and around the world. His success on the diamond was matched only by his business accomplishments off the field and capped by his extraordinary philanthropic efforts. We are heartbroken and thinking of his wife, Billye, and their children Gaile, Hank, Jr., Lary, Dorinda and Ceci and his grandchildren," Braves chairman Terry McGuirk said in a statement.

More than 44 years after his last game, he still ranks first on baseball’s all-time list in RBIs (2,297), second in home runs (755), third in hits (3,771) and fourth in runs (2,174). His career batting average was .305. The Hank Aaron Award has been given to the top hitter in each league, as voted on by fans and the media, annually since 1999.

Despite all of that, he will be forever defined by one swing of the bat, that for his 715th, arguably the most famous home run in baseball history.

That night in Atlanta, in the ninth season after the Braves moved there from Milwaukee, with a standing-room-only home crowd poised to witness history, Henry Louis Aaron, born on Feb. 5, 1934, in Mobile, Ala., slugged a fastball from Dodgers lefty Al Downing over the left-field fence.

Here’s how Hall of Fame broadcaster Vin Scully described what happened as Aaron crossed home plate and was embraced by his teammates and parents, Herbert and Estella.

“What a marvelous moment for baseball, what a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia, what a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking the record of an all-time baseball idol. And it is a great moment for all of us …”

There was no denying the serious racial overtones surrounding Aaron's pursuit of Ruth's record. As he approached it, there was such tension among his Black Braves teammates that they joked about not sitting beside him in the dugout for fear an assassin would shoot the wrong player.

Aaron mostly let only his closest friends know the pain he’d suffered. When he did speak about it, he typically spoke of how the hate and anger had impacted others. He would mention how his parents suffered. That bothered him deeply, he would say. Nor did he like that his teammates feared for his safety. "Don’t worry about me," he would tell them.

Sometimes, though, not often but sometimes, he would open up to people. He would take the letters from binders and boxes, many of them long since committed to memory, and read aloud.

“You are [not] going to break this record established by the great Babe Ruth if I can help it. Whites are far more superior than jungle bunnies. My gun is watching your every black move.”

Imagine playing the game you love more than almost anything in the world, and in climbing the highest mountain, you are confronted with an avalanche of hate.

“Vile,” former Commissioner Bud Selig, a close friend of Aaron’s, said. “You cannot comprehend that someone would be so moved to write something like that about another human being. I think anyone who knew Henry Aaron would tell you the same thing, that he was one of the finest and most decent people to walk this earth.”

On Friday, Selig issued the following statement on Aaron's passing:

“My wife, Sue, and I are terribly saddened and heartbroken by the passing of the great Henry Aaron, a man we truly loved, and we offer our love and our condolences to his wonderful wife, Billye. Besides being one of the greatest baseball players of all time, Hank was a wonderful and dear person and a wonderful and dear friend.

"Not long ago, he and I were walking the streets of Washington, D.C. together and talking about how we’ve been the best of friends for more than 60 years. Then Hank said: 'Who would have ever thought all those years ago that a Black kid from Mobile, Alabama, would break Babe Ruth’s home run record and a Jewish kid from Milwaukee would become the Commissioner of Baseball?'

“Aaron was beloved by his teammates and by his fans. He was a true Hall of Famer in every way. He will be missed throughout the game, and his contributions to the game and his standing in the game will never be forgotten.”

Aaron played on, conquering fear and confronting hate, and in the end, doing what he could to make this country better. His battle was different, but not unlike that of Jackie Robinson. Like Robinson, he did it all with strength and dignity.

In the end, Aaron refused to be defined by hate or fear. He would not be controlled by it. But he also never forgot, and long after he’d hit the last of his 755 home runs -- the most in history at the time -- in 1976, he would remain a blunt and unflinching advocate for civil rights in this country.

That he could still stir the embers of hate and ignorance did not bother him. He did this as recently as 2014, when he reflected on President Obama’s two terms in office.

“We have moved in the right direction, and there have been improvements, but we still have a long ways to go in the country,” he said. “The bigger difference is that back then they had hoods. Now they have neckties and starched shirts.”

The Braves were flooded with telephone calls and mail after that comment, but Aaron had spoken anyway, knowing there would be blowback.

“Hank Aaron’s incredible talent on the baseball field was only matched by his dignity and character, which shone brightly, not only here in Cooperstown, but with every step he took," Baseball Hall of Fame chairman Jane Forbes Clark said in a statement. "His courage while pursuing the game’s all-time home run record served as an example for millions of people inside and outside of the sports world, who were also aspiring to achieve their greatest dreams. His generosity of spirit and legendary accomplishments will live in Cooperstown forever. On behalf of the Board of Directors and the entire staff of the Hall of Fame, we send our deepest sympathies to his wife, Billye, and his entire family.”

His 755th and final home run came on July 20, 1976, as a member of the Milwaukee Brewers, off Angels right-hander Dick Drago. Aaron joined the Braves' front office shortly after his retirement and worked in a variety of jobs, including player development and community relations.

His home-run mark stood until Barry Bonds hit his 756th on Aug. 7, 2007. Some argued that Bonds did not deserve to have the designation of Home Run King because of his alleged use of performance-enhancing drugs.

However, Aaron recorded a gracious congratulatory message that was played on the giant video board at AT&T Park that night.

“I move over now and offer my best wishes to Barry and his family on this historical achievement. My hope today, as it was on that April evening in 1974, is that the achievement of this record will inspire others to chase their own dream.”

Long before that moment, baseball fans of another generation had a different kind of debate: Hank Aaron vs. Willie Mays.

Aaron and Mays followed one another’s career closely from across the country, each tracking box scores and highlights. Aaron’s hallmark was his consistency: 21 straight All-Star appearances and 20 consecutive years of at least 20 home runs. He hit .300 14 times and 40 or more home runs eight times.

He was such a complete player that Dusty Baker, a friend and teammate, once said the 755 home runs overshadowed the fact that Aaron was also a better pure hitter, baserunner and defensive player than almost anyone.

Among the notes Aaron saved was this one from fellow Hall of Famer Ernie Banks: “I am confident that a man of your caliber will instill in others the spirit and love that you have given to Major League Baseball. My heart and feelings are with you and your kind friendship will mean more to me than any other person in life. Proud to be your friend.”

Aaron and Selig became such friends during Aaron’s playing days in Milwaukee that they would attend Packers games together. Once, while standing behind the Packers bench, they watched as the great coach Vince Lombardi began screaming at his own players.

“The next thing I know, Henry and I are both running away from the bench,” Selig said. “I don’t know why, but we both had the same instinct. We laughed about it later.”

That small moment could stand as a moment of hilarity in a life defined by dignity and courage in the face of real danger. His greatness on the baseball field will stand forever as a testament to his gifts. His true greatness, though, was off the field, in the way he lived and the example he left for others.