The hot new pitch that's sweeping across the Majors

This browser does not support the video element.

“All pitchers today are lazy,” claimed two-time All-Star hurler Sal Maglie in The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers. “They all look for the easy way out, and the slider gives them that pitch.”

Maglie’s career took place mostly in the 1950s for the old New York Giants. He passed away in 1992. One can only imagine how he'd have reacted to the modern game, in which the "fastball count" no longer exists, and, increasingly, neither do fastballs as the primary pitch. Today's pitchers throw heaters barely more than 50% of the time (or less, only 46%, if you choose to not count a cutter as a fastball).

What they're doing, increasingly, is turning to a pitch that makes batters look like, well, this.

Are pitchers today lazy? Hardly. They work harder than ever to increase velocity, design new pitch types, and exploit the weaknesses of the opposing hitter. A lot of the talk is about increasing heat, which is by far the biggest driver of the 21st century’s ever-increasing strikeout rate. (The rate of four-seamers/sinkers at 95 mph or above is currently almost three times what it was in 2008). But one thing we probably haven’t talked about enough is just how much pitches move, especially, it seems, sliders.

That is, if we're still calling them sliders.

If the most recent trend was "elevated, high-spin four-seam fastballs," the current one is the extreme horizontal sideways sweep of breaking balls. Just look at how many sliders have more than 12 inches of break, towards a pitcher's glove side. The rate is nearly three times higher than it was in 2009, and double what it was just three years ago, a number you can get to using Baseball Savant’s handy new pitch movement search feature.

Part of that, certainly, is due to the “sweeper” craze over the last year or two, but the trend had been growing for seasons before that. Even if we remove sweepers and stick with the "regular" slider, we’re still seeing twice as many sliders with a foot-plus break as we did a decade ago.

***

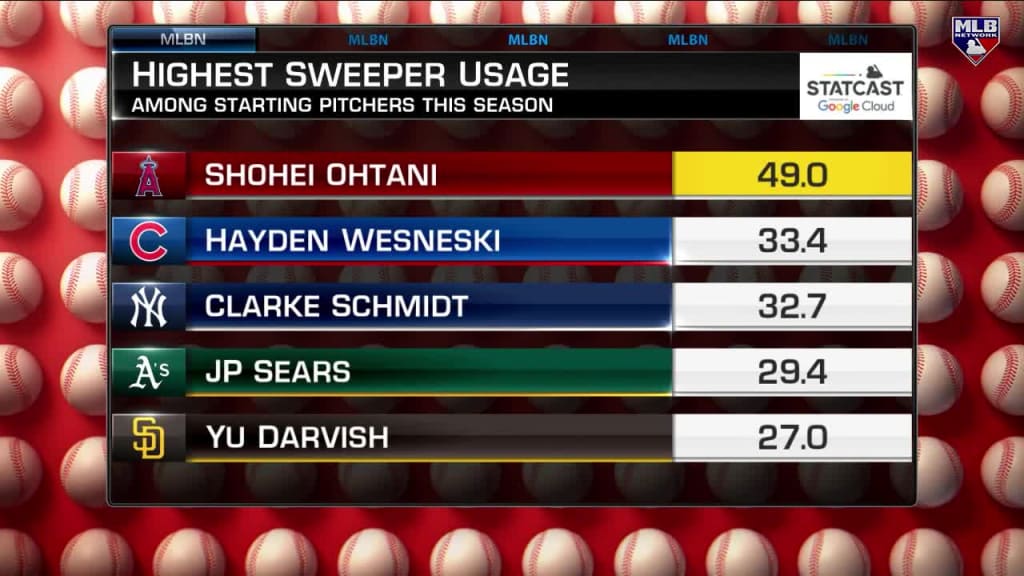

OK, break time. What’s a “sweeper,” as you’ve certainly seen all over your television broadcasts this year? It’s a slider that’s specifically intended to get a great deal of horizontal movement, and it looks a whole lot like this beauty from Shohei Ohtani, who is – to the greatest of all our surprises – absolutely fantastic at this, too.

It’s not that this is a pitch that just got invented in the last few years; certainly you can name pitchers from decades ago who threw a pitch like this, and maybe they even called it a sweeping slider, too. (Maybe even Maglie!) But it’s definitely a new trend_, one that really came to the forefront in late 2021, when MLB.com’s Tom Tango and Driveline Baseball’s Dan Aucoin (now with the Phillies) started using the term. That same month, the Athletic’s Eno Sarris started writing about the “Dodgers Slider,” and later on, Lindsey Adler wrote about the Yankees using the “whirly,” pitches which are now considered to just be: _sweepers.

So now it's a _thing_, and it’s got a lot to do with seam-shifted wake, if you want to get really deep about it – the science of how to use the orientation of the seams themselves to gain extra or unexpected movement. In large part, that’s why the trend has accelerated so quickly recently, because the shift of Statcast technology to Hawk-Eye in 2020 has really helped supercharge the ability to identify and teach this kind of movement. Go back to the movement chart above, and take another look. You can really see 2020 as that inflection point. Teams and coaches weren't wasting all that unexpected and unwanted downtime.

It’s gotten to the point, now, that it became necessary to label it as a separate pitch, as Baseball Prospectus did last year and MLB has done this season, because so many pitchers have become extremely clear that they now throw multiple different sliders with different grips for different purposes. Otherwise, you’re combining two dissimilar pitches into one label.

At the moment, 99 pitchers are classified as having thrown a sweeper since the start of 2022, though that’s a number that’s sure to rise as more such pitches are identified. Chris Bassitt, Ohtani and Yu Darvish are good examples of the 53 – and counting – pitchers who over the last two seasons have thrown a "regular" slider and a sweeper slider, which in large part is what requires a separate label here. Mariners prospect Bryce Miller (currently Seattle’s No. 2 prospect, per MLB Pipeline) helped make that especially clear by showing two sliders, with different grips, for different purposes. They're different pitches.

This browser does not support the video element.

So all that aside, what do they do differently? Combining 2022-23, just look at the movement profiles here, and realize how separate these pitches can be.

Sliders

- 85.1 mph

- 6 inches of glove-side movement, on avg.

- 41% have more than 6 inches of glove-side movement

Sweepers

- 82.2 mph

- 15 inches of glove-side movement, on avg.

- 98% have more than 6 inches of glove-side movement

You can see just how much extra frisbee-like movement we’re talking about, as Danny Young shows off here.

So it's clear this is a kind of pitch that moves differently, but what kind of outcomes does it lead to?

Sliders

- .280 BABIP

- 34% hard-hit rate

- 7% pop-up rate

- 34% swing-and-miss rate

Sweepers

- .255 BABIP

- 27% hard-hit rate

- 12% pop-up rate

- 33% swing-and-miss rate

It’s not as much about swing-and-miss rate as you might think. It's a whole lot more about getting a lot more weak contact. It's that first line – the Batting Average on Balls in Play – that stands out, perhaps in part because they’re so much better at getting pop-ups, which are essentially a no-value batted ball. There’s not really that much of a difference in swing-and-miss rate at all, perhaps counterintuitively, and it’s a terrible platoon pitch, as Ben Clemens wrote at FanGraphs last year. But for same-sided hitters, it’s a great weapon to induce weak contact.

Now: There is such a thing as too much movement, because if you’re getting it too far off the plate, then it’s easier for batters to lay off. (One study indicated that a slider with 6 to 14 inches more break than the fastball is ideal, but more than that reduces the effectiveness of the pitch.) And it’s not all “learn a sweeper, become an ace,” of course. As noted above, it comes with some pretty severe platoon splits, and for some pitchers it can hurt as much as it helps. Dodger righty Ryan Pepiot was quite open this spring about how his attempts to learn a sweeper last year actually hurt his other pitches, and he’s since shelved it entirely.

Still, there are countless good examples of pitchers who have survived and thrived by changing the shape of their slider. As we noted above, Ohtani is the best and most famous, but he was going to be good regardless, so we’ll pick two other cases, among many, to share with you. The first is that of Minnesota’s Caleb Thielbar, who was out of baseball entirely and ready to retire before returning to the Twins in 2020 – and who just struck out 80 in 59 1/3 innings in 2022.

“I can tell you that [Thielbar] probably bought himself a few extra years in the big leagues just by changing up his slider grip,” Driveline Baseball pitching coordinator Chris Langin told the Athletic.

See if you can see the difference between Thielbar’s two stints in the Majors.

Thielbar, % of sliders with 12+ inches of break

- 2013-’15: 10%

- 2020-’23: 80%

This browser does not support the video element.

Drew Rasmussen, who’s become one of the better starters on the red-hot Rays, has a similar story. Just look at what happened to his slider (which has become a sweeper) since his May 2021 trade from Milwaukee.

Rasmussen, % of [all] sliders with 12+ inches of break

- w/ MIL: 0%

- w/ TB: 37%

Want to see what that looks like? Thanks to MLB.com’s David Adler, we can:

So which teams do this the most? If we stick to “most sliders of all types with at least a foot of break,” then it’s the Rays (53%), followed by the Cubs, Padres, Mariners and Brewers. At the other end? The Rangers, Tigers and Guardians (5%). It's not the only thing the Rays stand out in -- their four-seamers have the most rise whether you include gravity or not, for example -- but it does tell you a lot about what they're up to.

What, then, about batters? It's not one size fits all, and it obviously matters who's on the mound. But the case of Toronto's Bo Bichette is instructive, because Bichette, while a talented hitter, has never been considered the most patient batter in the sport. Look at how he's been attacked this year, taking all pitch types into account:

Bichette, % of pitches faced with 12+ inches of break

It hasn't actually worked out well, just yet; Bichette is hitting .313 on those pitches. But you can see what teams are trying to do. You can see what pitchers are trying to do. The slider, or the sweeper, or whatever label you want to put on a pitch with this much movement, is what pitchers are choosing to pair with ever-higher velocity to get the best hitters in the world out. It's the latest trend -- and you know the top teams are already working on the next one.