The oldest league you never knew about

"I, for myself, think this field is haunted," Commissioner Chris La Rose tells me as he leans back in the century-old perch behind home plate. "In a good way. You walk around here and all the lights are off and it's dark, I can hear the old ballpark sounds, the sounds of old ballplayers."

"Hey, Chris!" a team manager suddenly yells from the field. "We have five runs, not three!"

"OK -- OK yeah, calm down," La Rose mutters back. "I'm trying to figure out this new scoreboard," he says to me, shaking his head.

La Rose changes the score and quickly flips on Van Halen's "Runnin' with the Devil" for the break between innings, tapping his foot with the beat.

-------------------------------------------------------------

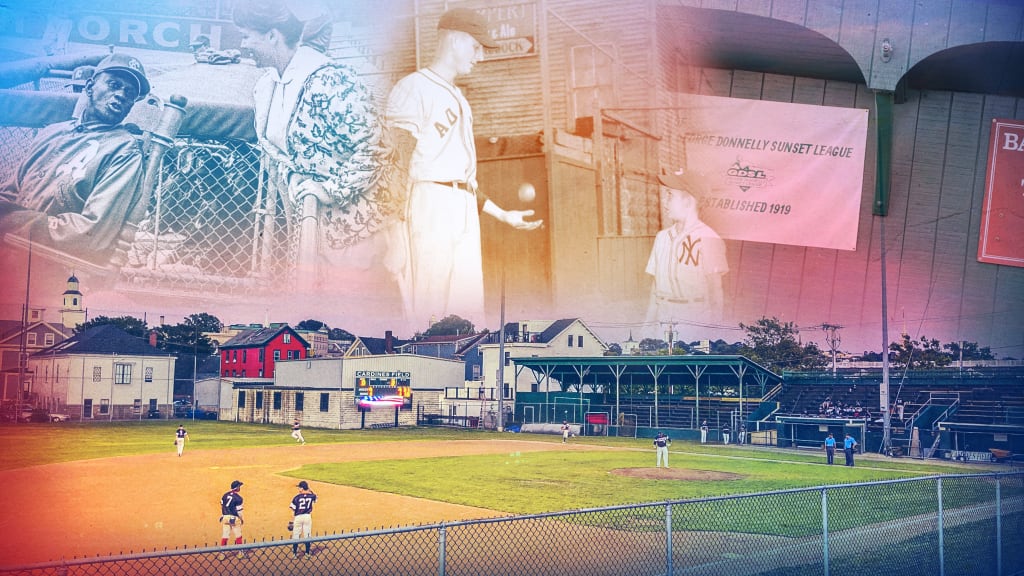

Newport, R.I., is an old town, but Cardines Field -- named for the first Newport native killed in World War I -- somehow feels even older.

Its beautiful green wooden grandstand -- standing in place since 1919 -- sticks out on America's Cup Avenue like it's been dropped there in a time machine, across the street from a large Marriott Hotel.

The outfield fence, although raised in recent years to protect homes, has also been the same for 100 seasons -- about 280-290 feet down both the left- and right-field lines, 400 to dead-center and then, to perhaps just drive outfielders absolutely insane, jutting back out to 315 feet in both right and left-center field. The boundaries snake around new condos and quaint side streets instead of the tenement buildings and churches of the 1930s and '40s.

And for all that time, baseball, George Donnelly's Sunset League Baseball -- an homage to former player and famed Newport sportswriter George Donnelly -- has been played inside. As Newport, and the world, has shifted and changed with newer sports, activities and pastimes, the country's second-oldest continuously-run amateur league in perhaps America's oldest ballpark has carried on.

"The ballpark has been around as a ballpark, you can go, some people say to the 1880s. Some people say 1909 was the first year," La Rose says.

That's older than Fenway Park or Wrigley Field. That's older than "oldest ballpark in America" Rickwood Field.

La Rose, who took the job of commissioner on a dare nine years ago after boasting he could do it, has since fallen in love with the history of the ballpark -- and who can blame him?

The area was first used as a water basin for neighboring steam locomotives in the late 19th century, but after complaints about the stagnant water by locals, the land was cleared. Railroad workers decided to then use the space to develop a baseball sandlot -- perhaps as early as the 1890s (it's still under debate). Long fly balls broke too many windows of nearby homes and businesses and the league was shut down. But again, in 1919, it was started up again as the still-existing sunset league to "provide working men with an opportunity to play ball." They've been playing here every summer, ever since.

If you thought the outfield dimensions were weird, you haven't heard all of it: The league owner's house was in right field up until 1936, with balls banging off it called doubles and hit over it, homers. Eventually, it was determined that this was not a good idea and the house was moved off the field of play.

Another quirk is that both dugouts are on the same side of the field, right next to each other. La Rose tells me it had to be that way because the railroad ran so close to the stadium on one side.

There was also a bar called The Paddock (later Mudville Pub) just off the first-base line that played a role throughout the stadium's history. Part of it, the front patio, sticks into the ballpark, while the other part is out on the street. The bar sponsored a team in the league and players used to frequent it after (and sometimes during) games.

"We know the umpires, we'd argue with them for nine innings and then go drink with them after," longtime player and coach Domenic Coro says. "A lot of times players would bring their friends there and they'd heckle people. On some occasions, the relief pitcher wouldn't know if he was relieving or not relieving -- so he'd kinda be over there in the sixth or seventh inning having some beers and then he'd have to get called in to pitch in the ninth."

"Yeah, the Paddock," La Rose laughs. "If you hit a grand slam, you got a case of Schaefer Beer."

The bar shut down a few years ago and, like most things, has since been transformed into an Airbnb.

Of course, today, in a COVID-19 world, no fans are allowed inside to watch games. That doesn't stop people from setting up lawn chairs beyond the left-field fence to cheer on friends and family members. One condo in left-center, the home of a former fighter pilot, La Rose tells me, has a big back porch where he can take in games whenever he pleases. The little roads that sneak in just outside center and right field, through some overhanging tree branches, are also great viewing points for some baseball action. A cyclist will stop in for a few minutes to see what all the fuss is about, or a mom with her daughter. A couple might have dinner and a ballgame just outside their front steps.

There are six teams in the league these days; that's mostly on par for what it's been since the early 1900s. The ages of players also fall on the younger side -- college athletes who need somewhere to play in the summertime. But in the past, there's been teams of dockworkers, fishermen, naval officers and firemen. The firehouse, still located across the street, has provided memorable moments for fire-fighting baseball players like Bob McPhee.

“He kept his fireman uniform in the dugout," PA announcer Bob O'Hanley said. "When that whistle blew, he would zoom into the dugout, change his clothes and run out and jump on the back of the fire truck as they picked him up.”

There were legendary local players like Earl Porter. He was a lefty and Coro says he used the short porch to his advantage, hitting "about 100 homers, maybe more home runs than anybody."

"Earl hit three home runs in one game," Coro recalls. "He had some of the tendencies of Babe Ruth, on and off the field."

George Donnelly Sr. dedicated his life to the league.

"My father, born in 1903, played his first season in 1922," George Donnelly Jr. said. "He was best known in his favorite position as catcher, but often pitched and played outfield. After 16 years, he retired from playing, but not from his involvement with the league’s activities. In the late 1920’s, he began scoring nearly all the games, and became their statistician/historian. During his active years, he was an excellent player, and is a member of the Sunset League’s Hall of Fame."

Marcus Wheatland, Jr. became the first Black player to integrate the Sunset League in 1920. The all-Black Union Athletic Club team played from 1934-35.

Lizzie Murphy, the "Queen of Baseball" and the first woman to play pro baseball, played for the Providence Independents in 1932.

Not many former big leaguers played in the Sunset League, but many played in the park itself. Bob Feller and Johnny Pesky played at points. Yogi Berra and Phil Rizzuto played at Cardines while stationed in Newport with the Navy. Jimmie Foxx hit there and said, "It's one of the finest parks in which I've played." Negro League teams like the New York Cubans, Indianapolis Clowns and Kansas City Monarchs barnstormed through the area to big crowds. But maybe the most famous Negro League player of all time did routinely pitch in the Donnelly league.

"The big thing was, when we had an all-star game, we'd have a ringer come in and pitch an inning," La Rose says. "That was a thing, especially with Negro League teams. Satchel Paige would come down and pitch his inning, sit in his rocking chair, he loved it. That was big. He would draw 3,000 people per game."

----------

Back in 2020, the game's now beginning to wind down as a tall lefty with long hair -- looking like a character straight out of "Dazed and Confused" -- mows down another batter. I also saw what I really wanted to see: a home run over the weird, jutting-out right-center-field fence. It hit some tree branches and disappeared into the surrounding neighborhood. The outfielder actually played it pretty well and didn't "run into the pole and knock himself out," like Coro told me can happen.

As I'm heading out the side gate, I look back and can't help but feel happy that a magical place like this still exists.

"I have four kids, my wife would take them down and there'd be a playpen in the stands. They basically grew up there," Coro, who coached both of his sons in the league, says. "It's been like a family affair for us. It's been part of my life, my family's life forever. My youngest daughter is the administrator for the website. I think I took my wife on our first date there. Even if you meet people who went to college and played, they kinda look back on the Sunset League even more than their college days."

Players and local leaders banded together to sponsor teams when the league fell short on cash in the '70s. They stopped the ballpark from being leveled and made into a parking lot mere minutes before a wrecking ball came crashing through in the mid-80s.

"This ballpark has survived its stay," La Rose says proudly. "It's kind of shocking. Once there's talk of trying to tear it down, people come out of the woodwork. There's tremendous history here and there's not much like it around anymore."

I finally, regrettably pull myself away from the field and head to my car. I drive off, past the moths dancing off the stadium lights and the sounds of spikes and wooden bats and lively infield chatter rising softly into the summer night.

Who's to say Cardines Field can't last another 100 years?