Hader has become a feast-or-famine fireman

This browser does not support the video element.

You can't hit Josh Hader, because he's the most unhittable pitcher in baseball, in the sense that you almost literally cannot make contact with his pitches.

In the entire history of baseball, among the nearly 25,000 pitcher seasons of at least 50 innings, he owns the fourth-best (2019, 48.4%) and fifth-best (2018, 46.7%) strikeout rate seasons. His career 44.4% strikeout rate is the best ever. Even within the context of baseball's steadily rising strikeout rates, there's never been anyone quite like him.

But there's something else going on, something that we first noticed way back in April and which has been apparent for the entire season: On the rare occasions you can hit Hader, you can really hit him.

Of the 30 hits he's allowed this year, 13 of them have been home runs, including Marwin Gonzalez's go-ahead three-run shot in Milwaukee's 7-5 loss on Tuesday. When he allows contact -- which, again, is incredibly difficult to do -- only seven pitchers, of the 424 who have allowed 50 batted balls, have surrendered a worse slugging percentage than his .837. (And of those seven, exactly one has lasted in the Majors all year without being cut or demoted: Edwin Díaz, who has a 5.60 ERA.)

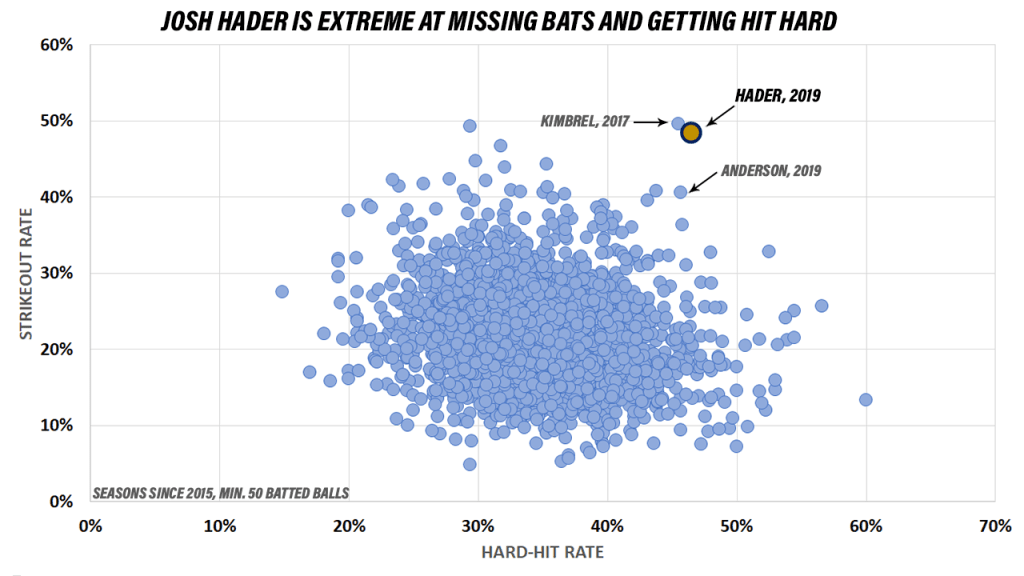

Hader doesn't need to worry about losing his roster spot, but his combination of elite bat-missing skills and atrocious damage-preventing skills is unmatched this year. It's just about unprecedented in the five years of Statcast tracking, actually, at least if we compare seasonal strikeout rate against hard-hit rate, for those seasons with a minimum of 50 batted balls allowed. That leaves us with over 2,700 pitcher seasons. Look where Hader's combination of 48.4% strikeout rate and 46.5% hard-hit rate puts him.

That's Hader up in the extreme upper right-hand corner of "lots of strikeouts and tons of hard-hit contact," with only Craig Kimbrel's 2017 coming anywhere near close. Hader, in 2019, is in the 100th percentile in strikeout rate -- obviously, no one is better -- and in the second percentile in hard-hit rate, which is to say that 98% of qualifiers have posted a better mark than he has. It's something like the ultimate all-or-nothing: You're probably getting nothing, but if you're getting anything, you might get everything.

The obvious question, then, is what's causing this. You might reasonably look at the 13 homers allowed this year -- the same amount he allowed in his first two seasons combined -- and assume he's getting caught up in the rising tide that threatens to shatter every Major League home run record this year. That might be true, but the causes behind that are more about how far the ball travels in the air; it doesn't cause his contact to be crushed contact.

Nor is this a continuing trend, though we saw it began almost as soon as 2019 did. Last year, Hader's hard-hit rate was in the 77th percentile, meaning it was well above average, better than about three-quarters of other pitchers. The year before, if he had qualified, he would have had one of the 30 best hard-hit marks. Whatever this is, it's a 2019 problem.

It seems clear that a lot of this is about damage on his fastball -- 12 of the 13 homers have come off the four-seamer, as well as 18 of the 19 extra-base hits he's allowed -- but perhaps not in the way you might think. After all, last year, all nine home runs Hader allowed came off the fastball, and that's not terribly unexpected when it's a pitch he throws 83% of the time. That's led to some questions about whether he should use his slider more to be less predictable. As MLB.com's Adam McCalvy wrote after Tuesday's loss:

Pina said he would talk to Hader about where he wanted that first fastball and would broach the idea of throwing more sliders. But Hader, who has heard this question a lot lately, is not going to suddenly start throwing a majority of sliders and changeups.

That may seem like he's simply being stubborn; then again, just look at his pitch usage (showing four-seam and slider only, for clarity) by month over his career. What you're seeing now isn't really any different from when he's been at his most dominant.

The fastball isn't slower; if anything, he's added a tick, up to 95.4 mph from 94.5 mph last year. There's not any terribly noticeable differences in spin or movement. In a lot of ways, he's still Josh Hader, even on the fastball -- his four-seam swing-and-miss rate is actually up this year from the last two. And yet, the hard contact. The blown saves. The concern from a team with a thin rotation on the edges of the Wild Card race.

It's a real problem, and not an easily solvable one, or else the Brewers would have done it, though it's interesting to note that this is their first season without highly respected pitching coach Derek Johnson, who departed to Cincinnati last winter in time to spearhead a stunning Reds pitching turnaround. But that doesn't mean it's a total mystery, either, because we've identified five factors playing into what's causing Hader to get this this hard.

1. Hader has been too predictable on the first pitch.

We just said that the fastball/slider combination isn't exactly the problem here, but that might not apply if we're just looking at the first pitch, because that's where Hader is getting hit hardest this year.

0-0 count: .412 average, 1.412 slugging, 5 home runs

All other counts: .129 average, .298 slugging, 8 home runs

There's always a little bias to those numbers -- you can't strike out on the first pitch, obviously -- but that's a lot of damage on the first pitch, and if there is a predictability problem, it might be here. Last year, Hader threw four-seam fastballs 73% of the time on the first pitch. This year, that's up to nearly 85% of the time. Among pitchers who have faced 200 hitters this year, only two have a higher first-pitch four-seamer rate.

That's a lot of first-pitch fastballs. It makes it a pretty good guess that you know what you're getting on the first pitch, and guess what...

2. Hitters have become much more aggressive on the first pitch.

... it's not like hitters don't know that. Gonzalez said as much on Tuesday.

"I was ready to swing at the first pitch. He’s one of the best in the game, and you cannot give him an easy strike. It was great to swing at the first pitch, and luckily, it was where I wanted it."

Well, of course. If you know what's coming, and you don't want to get behind in the count -- and heaven help you if you do, because when Hader gets ahead, batters have a .082/.109/.173 line -- going after that first-pitch fastball you're probably getting makes sense.

Just look what Oakland's Matt Chapman said after a first-pitch home run on Aug. 1.

“I wanted to hit the first good fastball I could jump on and not fall behind."

Right. Looking at the rate of first-pitch swings in Hader's three years, there's not just a trend. There's an explosion.

2017: 28.7% of first pitches saw swings

2018: 37.6%

2019: 44.6% (the second-highest rate in the Majors)

Meanwhile, Hader is throwing more first-pitch fastballs in the zone than ever. You can see the problem here.

This browser does not support the video element.

3. Those fastballs probably aren't hitting their spots.

Here's a repeated theme in postgame quotes from Hader: location.

July 13: “I felt good. I just made two mistakes, right over the middle of the plate. Can’t happen.”

Aug. 1: "It’s just one of those things where the location wasn’t the best today.”

Aug. 13: "It’s just one of those stretches. I feel like as a baseball player, we all go through slumps. Right now, it’s not locating pitches."

Location and command are notoriously difficult things to quantify, because it's nearly impossible to judge the intent of "missed spots." That said, there's definitely something happening here. In 2017, Hader's fastball crossed the plate at 2.61 feet above the ground. In 2018, Hader's fastball crossed the plate at an identical 2.61 feet above the ground. In 2019, Hader's fastball is at ... 2.99 feet above the ground. It might not sound like a lot, but it is. You might also say that the last two years, he threw 31% of his fastballs three feet or higher... and this year, that's 49%.

That's not a bad thing in and of itself. Pitchers across the sport are elevating their fastball with great success, so there's not a clear answer here. But if Hader is talking about it, and we can see that the fastballs are indeed different, there's probably something here.

4. He's allowing more balls in the air.

This one is simple, because it's just about the most 2019 thing: Hitters are trying to drive the ball in the air. See if you can see what's happened to Hader's ground-ball rate:

2017: 36.2%

2018: 31.1%

2019: 22.8% (the fourth-lowest rate in the Majors)

That's not very many grounders, and you can probably guess where this is going. Hitters are jumping on Hader's first-pitch fastballs, they're launching everything in the air, the hard-hit rate on those line drives and fly balls has skyrocketed -- 28.3% in 2017, 43.2% last year, and 54.9% this year -- and when you combine all of those things ...

5. He's allowing a ton more distance on fastballs in the air.

... ah. Yes. The average distance increase here on flies and liners off fastballs is not pretty.

2017: 290 feet

2018: 292 feet

2019: 319 feet (the seventh-highest rate in the Majors)

This part can't be separated from the aerodynamic changes that have fueled much of the home run explosion across the Majors in 2019, though all of the previous points ought to show you that some of the effect here is due to actions that have been made before the bat even contacts the ball.

Hader isn't "broken," or "ineffective," or anything like it. He's got, again, one of the best strikeout rates of all time. He may be the most unhittable pitcher who ever lived. But if you do hit him, you really hit him. In a world where relievers are expected to be perfect and anything less than that is considered a failure, you can see why that's so frustrating -- even if it's wildly unfair. In so many ways, Hader is an extreme. We've never seen anyone like him.