With no more shift, look for this player to rake

This browser does not support the video element.

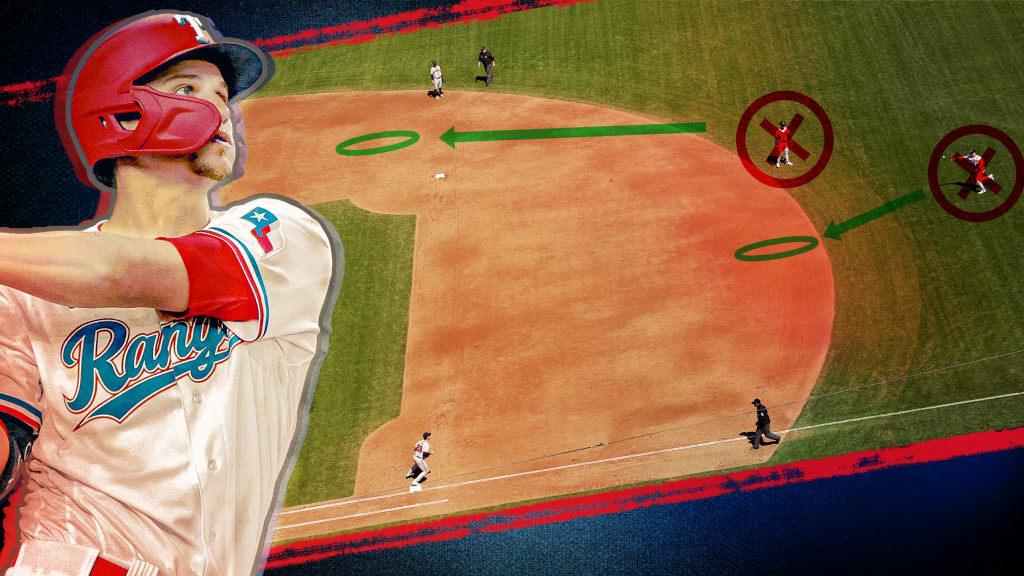

On Sept. 25, Corey Seager stepped to the plate against Cleveland’s Aaron Civale, and laced a hard-hit line drive to right field at 108 mph off the bat. This particular combination of exit velocity and launch angle has been a hit nearly 90 percent of the time since 2015; throw in the fact that it was hit to short right field, and it had been a hit for pretty much the entirety of baseball history before the last decade.

But that’s not how baseball in 2022 worked, of course.

Guardians second baseman Tyler Freeman, stationed 174 feet deep from the plate on the outfield grass, timed his jump perfectly. Seager’s no-doubt-hit-for-most-of-recorded-history was caught for an out. “Well, there we go again,” dejectedly expressed the Texas broadcast, no doubt having tired of seeing an entire season of Seager hitting the ball into the shift.

This browser does not support the video element.

But that won’t be true in 2023. Next season, baseball is going to look a little different, intentionally. The bases will be larger. There’s a limit on pickoffs. There’s going to be a timer, at long last. But the one that’s going to make baseball look the most different is clear: New restrictions on infield positioning that will popularly be referred to as “a shift ban,” even if that’s not entirely correct. Freeman would have been required to stay on the dirt. Seager would have likely been on first base, at least.

Though the overall effect of this is still TBD and might not be as significant as some might imagine, there are going to be a few hitters who find themselves quite pleased by the new rules, perhaps none more so than Seager – who, by Statcast analysis, might have regained 20 hits that didn’t quite make it through in 2022, the most of any hitter in baseball, ahead of Kyle Schwarber and Carlos Santana.

We’ll follow up with a look at other hitters and how they may be affected in an upcoming piece, but let’s focus on Seager today. What makes him stand out above everyone else – and how did we come up with 20 hits?

Why was Seager hurt more than anyone else?

The first question you want to know is Why Seager? What it is about him that makes him stand out from everyone else in this regard? Before we even explain how the data works, the answer is that he was available and predictable. Seager got into 151 games and posted an above-average contact rate, all while being shifted on 93% of the time. So the end result is that he made contact with 481 batted balls against a full or partial shift, easily the most of any lefty. He pulled 107 grounders into the shift, also the most, leaving a massive gap between Charlie Blackmon’s 86 in second place.

Seager is a great hitter, but he’s a predictable one, too. If you’re hitting more pulled grounders than any other lefty, well, that’s how you get shifted 93% of the time. Of those 107 pulled grounders into a full or partial shift, he managed all of six hits – a .056 average – and some of those were fluky, like when the shift worked but the fielder just couldn’t convert.

This browser does not support the video element.

So that’s the short version: Seager likely lost the most hits because he hit the most balls in the shift. He might not be atop this list if every lefty hitter played as much as he did, made contact as much as he did and pulled as many balls on the ground as he did. That a similar but different analysis from Sports Info Solutions also had Seager as losing the most hits points to that fact, as well.

We should make it exceedingly clear that any analysis of this topic, whether it’s written here, there, or anywhere, is at best an estimate, for three very good reasons:

1: You can look at 2022’s batted balls and look at where fielders under the 2023 rules might be standing, and judge the positioning, but you can’t guarantee that fielder on that day actually completes the play or not; fielders matter.

2: We can’t just assume hitters will hit like they did under the old rules against the new rules; we have no idea, until we see it in action, if batters will stop trying to hit it over the shift (costing power) in an attempt to get through the newly opened gaps (adding batting average). Some probably will. Others just won’t. There’s so much we don’t yet know.

3: There’s still plenty of room for teams to position batters differently within the new rules. It’s not like the four infielders all have to stand at the four ‘traditional’ spots. They don’t, and won’t.

You can really see that last point here, just by looking at where fielders were positioned in 2022 against lefty batters without the shift on. Shortstops basically stood up the middle. Second basemen played much deeper than third basemen. With the exception of pulling in a few of those too-deep second basemen to be on the infield dirt, little about this would need to change for 2023.

For this reason, you can’t just look at things like “most hard-hit groundouts against the shift,” because some of those outs would be outs no matter what, like this one. It's into the shift, but: is it, really?

This browser does not support the video element.

That said, Seager isn’t suddenly going to hit like Steven Kwan or Joey Gallo next year. He’s still Corey Seager. So what does that look like?

Where Seager lost his hits

If “20 hits lost for the by-far-most-victimized player in baseball" doesn’t sound like much, that's a matter of perspective. For Seager, it's a difference of 30 points in batting average (more on that below), which would probably feel pretty significant to Rangers fans.

Let’s explain how we got here. For Seager, he stepped to the plate 663 times, but that doesn’t mean the shift had 663 opportunities to take hits away, because we need to remove these categories:

No contact: strikeouts, walks, hit by pitches

No defense: home runs

No shift: He was shifted 93% of the time, but 93% is not 100%

Big distance: Balls hit more than 220 feet, beyond any shifted infielder

(To be clear: There is ample evidence that the shift does include minor effects on strikeouts and walks, differently for lefty and righty hitters. This goes somewhat to the approach changes we mentioned above, but we’re focusing just on in-play balls here.)

All of which leaves us with 262 Seager batted balls, with a full or partial shift on, which didn’t go more than 220 feet – or just under 40% of his plate appearances. That’s actually a considerably higher number than the average lefty batter (25% of plate appearances) or righty batter (11%), which is all part of why a positioning restriction will matter a little, but not a lot, for most players.

The way we get to an estimated 20 regained hits is simple. First, let’s take a play where Seager hits a ball hard into the shift, for an out. This May example in Houston is a perfect one.

This browser does not support the video element.

Based on the way Seager hit the ball (how hard and how high), it’s a hit 31% of the time. Throw in the horizontal spray angle, and that combo of factors is a hit 47% of the time. Throw in the actual position of the fielder too, and it’s a hit just 6% – not 0%, because fielders matter, and sometimes fielders do not make plays. But that last number doesn’t matter so much, because that’s an illegal fielding position in 2023 anyway.

Given that Seager got an out on the play – i.e., a 0% outcome – we’ll credit him with +.47 of a hit, or the usual outcome of a ball hit that hard, that high and at that spot on the field.

Do it for all of those 262 plays. This one, against the White Sox? A 0% outcome, but against a now-illegal defense, so we’ll give him +.76 for the 76% of the time this exit velocity, launch angle and spray angle against neutral lefty batter no-shift positioning becomes a hit.

This browser does not support the video element.

This one, against the Red Sox? Realize that’s the shortstop who makes the play, which can’t happen in 2023, but it’s a lower (31%) chance of a hit than the one against the White Sox, because it’s still a grounder in the infield, in a spot where a non-shifted infielder has a chance to get it. Give him his +.31, rather than the 0 he got.

This browser does not support the video element.

It’s worth noting, though, that it’s not all gains. There are some likely losses, too.

For example, last July, Seager got a hit by doing what people have been calling for lefties to do for years, which is to go opposite field against the shift. It worked well, giving him a 100% outcome – i.e., a hit.

This browser does not support the video element.

But remember, in 2023, there won’t be a lone fielder on the left side. There will be two. It’s going to be less likely for this kind of ball to get through – 32% by our numbers – which means he’s demerited -.68 here.

That’s the idea, though. We kept the six hits he had against regular, not-shifted defenses, and applied the expected number against all of his non-homer batted balls (under 220 feet) against partially or fully shifted defenses, aggregating all those fractions into a total. In real life in 2022, he had 60 non-HR hits of under 220 feet against the shift; by this method, he might have been expected to have 80. Thus, your +20.

What would it have meant to him?

We’ll add the 20 hits here, calling them all singles, but remember that there’s likely to be some impact on walks, strikeouts and approach, which we’re not attempting to account for here.

- In 2022, Seager hit .245/.317/.455, a .772 OPS.

- In no-shift 2022, Seager may have hit .278/.347/.489, an .836 OPS.

Remember, Seager was arguably most affected of any hitter in baseball, so most players won't see a gap this large. But 33 points of batting average and 64 points of OPS are nothing to sneeze at. The analysis of Seager's first year in Texas would certainly be a lot different had he put up that second stat line there.

Of course, there's one other aspect, too. Again, we’re applying 2022 spray charts to 2023 rules, without trying to adjust for what a hitter may likely do differently. Take Seager himself, dating back over the last five seasons.

Since 2018, Seager has seen a shift on 75% of his pitches, giving us a tidy one-quarter without. Against the shift, as you’d expect, his batting average on balls in play (.286) is lower than it is against a standard defense (.305), as this is the primary point of even playing a shift. But his slugging percentage is much higher against the shift (.501) than it is against standard defenses (.443), in part because he hits the ball harder (46% hard-hit rate) against it than he does without it (43%), and that essentially cancels out the gains of the extra singles.

It will, as always, continue to be a mind game. Hitters like Seager will likely have a somewhat easier time getting a single, if they want it. They may not want it. It might not be advisable to want it, if it comes at the expense of power. It will be fascinating to see who chooses what approach.