Here's why you can't believe in Derby 'curse'

Every year around this time, the same thing happens: Eight sluggers get selected to participate in the Home Run Derby, and eight fanbases begin to panic. They worry that doing so will "mess up their swing" and doom them to a less productive second half. They remember examples like Bobby Abreu in 2005, when he entered the break with a .955 OPS, hit 41 homers to win the Derby and then posted a mere .787 OPS in the second half, as his Phillies team finished two games out of first place.

Why, the thinking goes, would you bother risking important games in a potential playoff push simply to take part in what is a fun but ultimately meaningless exhibition?

In a baseball world where teams are looking to gain or maintain even the slightest edges, that would be a valid concern ... if it were true. It's not, at least not in the way that you think. While it's true that guys who hit in the Home Run Derby tend to do worse in the second half, it's more true that All-Stars who don't participate in the Derby tend to do worse in the second half -- and no one talks about the "All-Star curse," do they?

We first looked into this back in 2017, for what it's worth, but the myth seems to persist, so it's worth revisiting. It's true that a lot of these players have lesser numbers in the second half. It's also true that there are two very good reasons for that.

First, the simple one:

1) The "first half" isn't really a half

Right. The first half never ends at the 81-game point of the season. In 2019, for example, Marcus Semien reached the break with 424 plate appearances. You will notice he did not end the season stepping to the plate 848 times, because his Oakland team had already played 92 games. So if you view a second-half decline as "he hit fewer home runs than he did in the first half," that's a function of time as much as anything.

Now, the more important one:

2) You often get chosen to be in the Derby because you're having a great first half

This is the thing. This is the thing all the time. If you're an entrant in the Home Run Derby -- or the All-Star Game -- it's because you're by definition having a wonderfully great first half, often better than you've ever done before. You've been healthy. You've been productive. Those are often things that are difficult to maintain over the course of a full season.

When we dug into this back in 2017, the way we showed this was to compare Home Run Derby participants in 2014, '15 and '16 to All-Star hitters in those three years who weren't in the Derby. As the results showed, "being in the Derby" didn't, on average, hurt hitters any more than "being an All-Star" did. That makes sense, intuitively, because both groups of players likely had to have a great first half to get there, and not everyone can keep that up.

As we continue through the years, we see that nothing has changed.

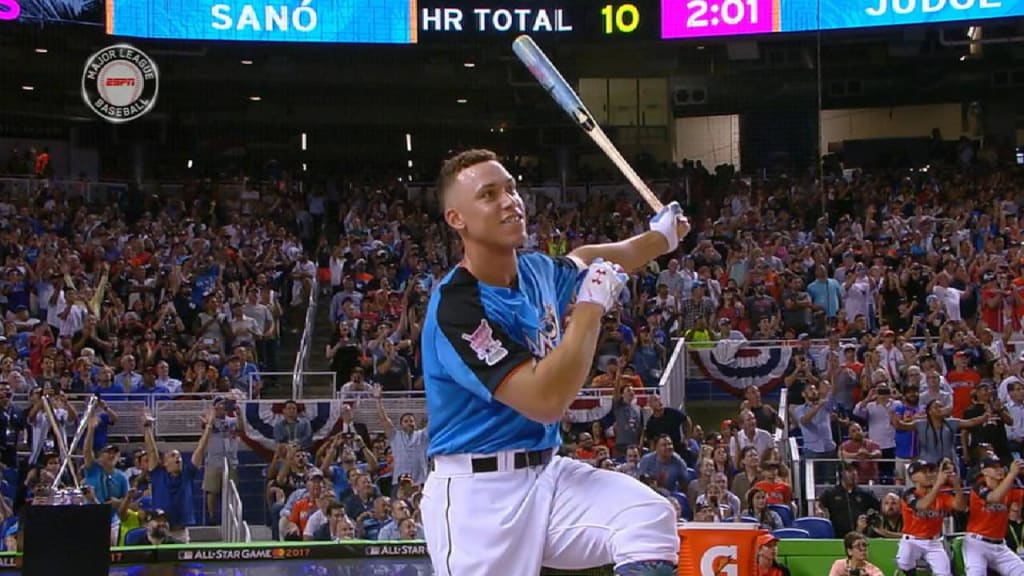

In 2017, the eight Home Run Derby players in 2017 declined from .945 in the first half to .934 in the second half, which is to say they barely declined at all. They performed about the same. Meanwhile, the non-Derby All-Stars who got into the game dropped from .905 in the first half to .818 in the second half. That's an 87-point drop, far more than the Derby participants, full of stories like Corey Dickerson posting a .903 OPS in the first half and a .690 OPS in the second half.

When you look specifically at the eight Derby guys, well, the myth doesn't even hold up, to be honest, because we don't even have to explain why it's unusual that some hitters would do worse in the second half. Three of them didn't.

These five players did worse after the Derby, if we look at simple OPS...

-.200 points // Aaron Judge, 1.139 to .939

-.164 points // Miguel Sanó, .906 to .742

-.074 points // Justin Bour, .923 to .849

-.065 points // Mike Moustakas, .863 to .798

-.060 points // Cody Bellinger, .961 to .901

... and these three players got better.

+.162 points // Giancarlo Stanton, .933 to 1.095

+.114 points // Charlie Blackmon, .950 to 1.064

+.046 points // Gary Sánchez, .850 to .896

So right away, there's not much here -- Stanton, you might remember, had his swing screwed up so badly that he went on to hit 59 homers that year -- and it falls apart even more when you realize why some of those declines happened. Sanó injured his shin in August and missed most of the second half before undergoing surgery. Bour injured his oblique. Bellinger missed time with an injured ankle; Judge was still one of the 15 best hitters in baseball in the second half.

Participating in the Derby doesn't hurt you so much as simply being an All-Star does, because you're specifically selecting players who got off to fantastic -- and in some cases, unsustainable -- starts.

This browser does not support the video element.

In 2018, at least, the Home Run Derby players did get worse, on the whole. They declined from .908 in the first half to .866 in the second half. That might seem to confirm the myth, that there was a 42-point drop from the first half to the second half among participants. It might, except that the the non-Derby All-Stars who got into the game did much, much worse. They declined from .884 in the first half to .808 in the second half. That's a drop of 76 points.

So again, it wasn't the Derby that hurt you. It was being an All-Star, it was having a first half where usually almost everything went right, in ways that are hard to keep up all year.

These five did worse ...

-.235 points // Jesús Aguilar, .995 to .760

-.133 points // Kyle Schwarber, .873 to .740

-.111 points // Freddie Freeman, .938 to .827

-.094 points // Max Muncy, 1.013 to .919

-.026 points // Javier Báez, .892 to .866

... one did about exactly the same ...

-.006 points // Alex Bregman, .928 to .922

... and these two did better.

+.139 points // Bryce Harper, .833 to .972

+.069 points // Rhys Hoskins, .819 to .888

This browser does not support the video element.

In 2019, it was more of the same. The eight Home Run Derby participants dropped 41 points of OPS, from .919 to .878. All the other All-Stars who got into the game but didn't hit in the Derby dropped 45 points, from .918 to .873.

As usual, if you look at the eight sluggers, some got worse, and some got better. There's not much rhyme or reason here.

Four did worse ...

-.244 points // Josh Bell, 1.024 to .780

-.143 points // Pete Alonso, 1.006 to .863

-.103 points // Carlos Santana, .958 to .855

-.101 points // Matt Chapman, .890 to .789

... one did about the same ...

+.002 points // Ronald Acuña Jr., .882 to .884

... and three did better.

+.207 points // Alex Bregman, .927 to 1.134

+.060 points // Vladimir Guerrero Jr., .741 to .801

+.051 points // Joc Pederson, .855 to .906

While Bell's drop-off looks enormous, there was a larger issue there, which is that even at the time it was clear that what he was doing in the first half seemed out of character, and it was. He hasn't come within 200 points of OPS of what he did in the first half of 2019 in his entire career in any half before or since the Derby.

We can't guarantee that participating in the Derby is going to help your swing, though it certainly didn't hurt Harper last year. All we can say for certain is that it's not going to destroy it, not any more than just showing up in town as an All-Star might otherwise.

It's a self-fulfilling prophecy, really. You don't get into either the Derby or the Game without having had an incredibly impressive first half. But by virtue of having done that, you've now likely set up expectations that are nearly impossible to match. We don't talk about the "All-Star Game curse," really, not nearly as much as the supposed Derby curse. Maybe we should.