How Nomo changed MLB forever

This browser does not support the video element.

A version of this story was first published in February 2022.

It’s difficult to imagine Major League Baseball today without the talent and influence of Japanese players.

There is, of course, two-way sensation Shohei Ohtani, now a three-time MVP Award winner and owner of a record-breaking contract. And the list goes on from there: Shota Imanaga, Yoshinobu Yamamoto, Yu Darvish, Kenta Maeda, Masahiro Tanaka, Hiroki Kuroda, Hideki Matsui, the great Ichiro Suzuki and many more. And that's before Roki Sasaki leads the next wave of talent into the Majors in 2025.

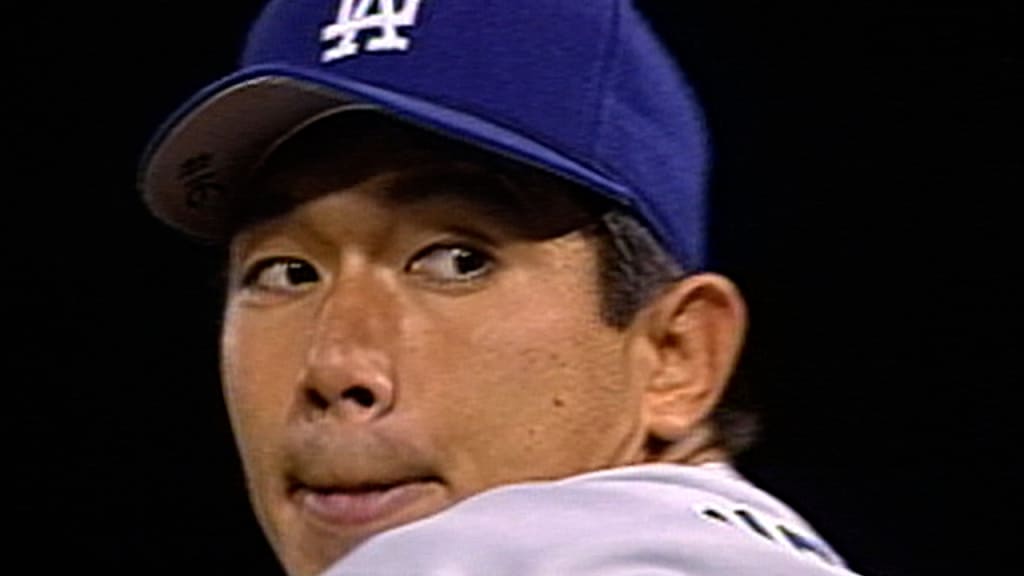

But before them all, there was Hideo Nomo.

It was 30 years ago this week that MLB changed forever -- for the better -- when the Dodgers officially announced a deal with Nomo, on Feb. 13, 1995. It turned out to be a seismic event. In the previous 29 seasons, no Japanese players had appeared in the Majors. In the 29 seasons since Nomo’s '95 NL Rookie of the Year campaign, nearly 70 have followed in his footsteps, including those aforementioned stars.

With the benefit of hindsight, it seems like this wave was bound to arrive, sooner or later. Perhaps it was. But there was nothing simple, easy or guaranteed about the success of Nomo’s pioneering leap.

• Japan's most influential MLB players

A dream forms

Nomo joined the Kintetsu Buffaloes of Nippon Professional Baseball’s Pacific League as a 21-year-old in 1990 and was an immediate standout, winning the league’s pitching Triple Crown, not to mention its Rookie of the Year and MVP honors. He also took home the Sawamura Award as the NPB’s top pitcher. But even before that point, he dreamed of competing in the Major Leagues.

When Nomo was introduced as a Dodger, he recalled that the feeling dated back to the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, South Korea, where baseball was a demonstration sport. Japan lost the title game to the U.S. that year, although Nomo tossed 1 2/3 scoreless innings of relief.

If he already harbored a desire to test himself across the Pacific, the MLB Japan All-Star Series held after the 1990 season only served as reinforcement. Nomo pitched in exhibition games against a visiting squad of MLB stars, and the right-hander with the corkscrew delivery made a distinct impression.

“Whether it was Lenny Dykstra or Ken Griffey Jr. or Barry Bonds or any of the guys that were on the trip, they’re all talking in the dugout like, ‘Holy cow,’” pitcher Rob Dibble later recalled on the ESPN 30 for 30 podcast episode, “The Loophole.”

According to author Robert Whiting’s book, “The Samurai Way of Baseball,” one American pitcher went out of his way to encourage Nomo. Randy Johnson, coming off his first All-Star season in Seattle, approached Nomo at a private dinner during the trip and, in Whiting’s account, “told him he was wasting his time playing in Japan.”

“You belong in MLB,” Johnson said.

Squeezing through a loophole

There was precedent for a Japanese player coming to the Majors -- but not much.

Way back in 1964-65, a young left-hander by the name of Masanori Murakami had pitched in 54 games for San Francisco -- all but one in relief -- and found some success. His stint was the result of a deal between the Pacific League’s Nankai (now SoftBank) Hawks and the Giants, but there was some controversy over the terms, and Murakami soon returned to Japan. A subsequent agreement between the U.S. and Japanese leagues effectively slammed the window shut on the next Murakami. It remained that way for nearly 30 years.

This browser does not support the video element.

Unlike today, there was no posting system through which NPB players could make the jump to MLB. Instead, they were simply bound to their teams, at least until reaching 10 years of service time. It seemed to be an intractable problem, but a confluence of the right people at the right time -- with a heavy dose of chutzpah -- changed the course of baseball history.

There was Don Nomura, a young, half-Japanese sports agent who was looking for the right player to challenge the system, along with his U.S.-based counterpart, Arn Tellem. There was Jean Afterman, then Nomura’s sharp-eyed lawyer and now a longtime assistant general manager and senior vice president with the Yankees. And there was, of course, Nomo himself. This project would require not just a great player but somebody who didn’t mind going against the grain -- and taking heat for it.

“It was clear that Hideo wanted this challenge,” then-Dodgers GM Fred Claire told JAPAN Forward in 2020.

“He was willing to risk his reputation in Japan. He was willing to risk what he had accomplished as an outstanding and popular player in Japan. He was willing to put all of that on the line, not knowing whether he would be successful, but believing in himself, and that’s why Hideo was a true pioneer. He had the confidence in his ability and he had no fear.”

Nomura met with Nomo, who stated his desire to come to the U.S., and he also recruited Afterman and Tellem to the cause. As Nomura and Afterman later described on the 30 for 30 podcast, the team discovered that only active Japanese players were specifically forbidden from heading to MLB. The solution: Nomo had to retire.

It wasn’t quite that simple, though. Kintetsu would have to put Nomo on the voluntarily retired list, and why would the club take such a step with a star pitcher? Nomura cooked up a strategy that involved Nomo demanding an expensive, six-year contract from Kintetsu. This sort of thing was unheard of in NPB at the time, and when Nomo refused to back down, the team’s brass was furious enough to eventually place him on the list. What seemed like a punishment played right into Nomura’s plans.

Not that everything went smoothly after that. Nomura recalled getting death threats for a move that some perceived as destructive to Japanese baseball. Initially, Nomo was crushed in the Japanese press, and according to Whiting's book, even Nomo's father was upset enough about how the situation played out that the two stopped speaking for a while.

“I lost a lot of friends,” Nomura said on the podcast. “Same with Hideo.”

A Tornado in L.A.

Once Nomo set his sights on the Majors, there was significant interest. Reports at the time indicated at least six teams were in the mix, including the Dodgers, Giants and Mariners.

What sealed the deal was the involvement of the Dodgers’ then-owner, Peter O’Malley. Both sides described an instant connection that formed between him and Nomo and led to the pitcher picking L.A., despite having to settle for a Minor League contract (with a $2 million signing bonus).

And with that, the circus began. First was the introductory news conference, which was packed with camera crews, photographers and writers. Then came the start of Spring Training, with The Los Angeles Times describing how a crowd of Japanese media staked out Nomo’s arrival at Dodgertown in Vero Beach, Fla., and chased his car around the parking lot. That set the tone for the level of scrutiny Nomo would be under all year as his home country followed his exploits.

“The guy couldn’t go anywhere, he couldn’t walk anywhere, without a huge contingent of reporters following him around,” Dodgers first baseman Eric Karros recalled to The Times. “It was basically 24/7.”

(In one amusing example from the 1995 All-Star Game in Arlington, relayed by Tony Gwynn, a camera crew doggedly followed Nomo straight into the clubhouse bathroom before realizing where they were and retreating.)

The attention and pressure were relentless. What would happen to Nomo -- and to other would-be Major Leaguers from Japan -- should he fail? If any of that bothered Nomo, he didn’t let it show.

This browser does not support the video element.

The start of the 1995 season was delayed by the strike, and Nomo made one tuneup start in Class A. But then it was time. The Dodgers called up the 26-year-old righty to make his debut against the Giants at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park on May 2, 1995, and he allowed just one hit over five scoreless innings.

Nomo’s first month in the Majors was decent but uneven, but he soon hit his stride. The man dubbed “The Tornado” for his twisting windup unleashed his plummeting forkball (a relative of the splitter) on the National League, to devastating effect. (In Gwynn’s words to the L.A. Times, it was “impossible to tell whether it’s a forkball or a heater until that sucker drops a foot at the end.”) Over a 13-start span from June 2-Aug. 10, Nomo averaged nearly eight innings per outing, posted a 1.31 ERA, allowed a .419 opponent OPS and struck out nearly 30% of the hitters he faced.

• The funkiest windups in MLB history

In the middle of that run, he started the All-Star Game, matching Johnson, his AL counterpart, for two scoreless innings during which he struck out Kenny Lofton, Edgar Martinez and Albert Belle. Around that time, he was on the cover of Sports Illustrated, among other major publications.

This browser does not support the video element.

Nomo finished the year 13-6 with a 2.54 ERA, led the NL in strikeouts (236) and helped the Dodgers top the Rockies by one game for the NL West title. He also beat out future Hall of Famer Chipper Jones for the NL Rookie of the Year Award.

This browser does not support the video element.

A legacy established

Nomo was superb again in 1996, finishing fourth in the NL Cy Young voting for the second straight year and tossing a memorable no-hitter on Sept. 17 at Coors Field.

• Ranking Dodgers' top 5 pitching gems

He was never quite the same after that, perhaps feeling the effects of his heavy early-career workload in Japan. Nomo dealt with some injuries, and his production slid. Between June 1998 and December 2001, he bounced around seven organizations, although he did throw a second no-hitter along the way, for Boston in '01.

This browser does not support the video element.

• Japanese pitchers who have thrown no-hitters

Nomo found new life after returning to L.A. in '02, putting together consecutive stellar seasons. That would prove to be his last hurrah, however, as Nomo struggled to a 7.95 ERA over the rest of his career, finishing with a short stint for Kansas City in '08.

This browser does not support the video element.

Nomo was elected to the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame in 2014, but when it came to Cooperstown, Nomo’s candidacy died that same year, when he got 1.1% of the vote and fell off the Baseball Writers’ Association of America ballot. That’s to be expected, given his good but hardly spectacular career numbers. But if the Hall ever opens a wing of its Plaque Gallery for trailblazers who made a profound impact on the sport’s history, Nomo would be an obvious choice.

So many others have followed and thrived in his wake, leading to our current “Sho-Time” Era. Fellow pitcher and friend Shigetoshi Hasegawa became an All-Star reliever, “because of Nomo.” Ichiro arrived via the new posting system, for which Nomo paved the way. Japanese kids such as Nori Aoki -- a future six-year MLB veteran -- grew up watching Nomo pitch in the Majors on TV and rethought the trajectory of their baseball futures.

"[Nomo] definitely established a road for Japanese players to come over here," Maeda told NBC News in 2018, via translator Will Ireton. "In that way, he had a tremendous impact for all of us, including myself."