Ghosts of legends join Braves in Milwaukee

MILWAUKEE -- When the Braves last played a postseason game in Milwaukee, Hank Aaron was the cleanup hitter, Eddie Mathews was at third base and Bob Uecker was a power-hitting prospect. That’s not a joke. In 1958, Uecker was coming off a 22-homer season in the Minors.

It was Oct. 9, 1958, to be exact, a 6-2 win for Mickey Mantle’s New York Yankees in Game 7 of the World Series. Milwaukee had defeated the mighty Yankees one year earlier in another seven-game Fall Classic after being derided as “Bushville” in the New York papers. It was all part of the first golden era of baseball in Milwaukee, as the Braves put the city in the big leagues and the city responded by making the Braves the first National League team ever to draw two million fans.

And yet, six years after those back-to-back World Series, the Braves were petitioning to move to Atlanta. Two years after that, they were gone.

Now, 63 years since their last postseason appearance here, the Braves are back. Game 1 of the Braves-Brewers National League Division Series is Friday at American Family Field.

“To me, I’m glad to see the Braves there,” said Rick Schabowski, who edits a quarterly newsletter for the Milwaukee Braves Historical Association. “I have no animosity toward the Atlanta Braves. I mean, how can you be upset at Henry Aaron and Eddie Mathews when they were your childhood heroes?”

• • •

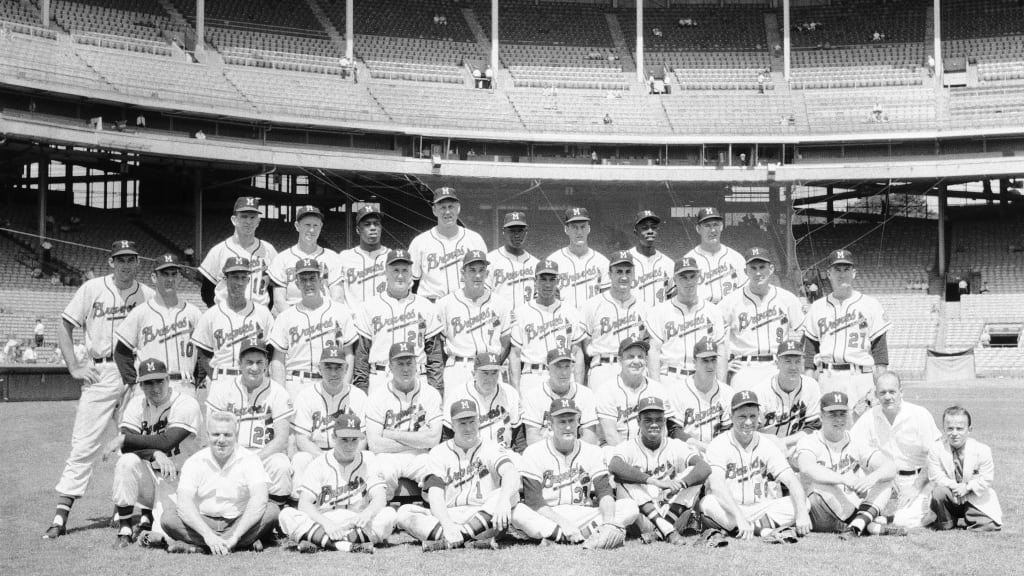

The rise and demise of the Braves in Milwaukee is a story of love, loss and affordably priced lager. The team never had a losing season while calling Milwaukee County Stadium home from 1953-65 and fielded Hall of Famers Aaron, Mathews, Warren Spahn, Red Schoendienst, Phil Niekro, Joe Torre and -- ever so briefly at the end of his career -- Enos Slaughter.

Hints of that era remain. There is a Milwaukee Braves Wall of Honor on the facade of American Family Field in the left-field corner. At an adjacent Little League field on the site of since-razed County Stadium, a plaque and monument tell the story of the Milwaukee Braves. And between the two fields stands a life-sized statue of Aaron in his prime, depicted in his simple right-handed batting stance wearing a Milwaukee Braves uniform.

“That was a very big deal” when the Braves moved from Boston to Milwaukee in 1953, said former U.S. Senator Herb Kohl, who grew up in the nearby Sherman Park neighborhood and attended games with a boyhood friend named Bud Selig. “It turned out they were an emerging team with some wonderful players. Henry Aaron. Eddie Mathews. Warren Spahn. It was a great time in Milwaukee because we got a Major League team for the first time. Fans were crazy about them.”

This browser does not support the video element.

Kohl later owned the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks, but Selig’s heart was always with baseball. In 1963, with money he earned working at his father’s Ford dealership, Selig invested in the club under their new ownership led by Bill Bartholomay, ultimately becoming the team’s largest public shareholder. Support for the Braves in Milwaukee had been declining, however. After the team finished no lower than third place in the NL while drawing at least 1.4 million fans in each of its first eight seasons in Milwaukee, attendance fell to 1.1 million for a fourth-place finish in ‘61 and 766,921 for a fifth-place club in ’62. And when the Washington Senators moved to Minneapolis in 1961 and became the Minnesota Twins, it sliced into the reach of the Braves’ radio network.

The Braves’ decline may have been accelerated by Milwaukeeans’ love for cheap beer. For years, fans were permitted to bring their own cold beverages to Braves games, but on March 6, 1961, the Milwaukee County Board approved a ban of carry-in beverages, with fines up to $500 or up to 90 days in jail. That didn’t sit well with thirsty locals. An effort called "Operation Six-Pack” collected tens of thousands of signatures opposing the ban, and if those folks were not mad enough, the Braves proposed hiking the cost of a 12-ounce beer from 30 cents to 35 cents in ‘62.

Thirty-five cents!

Ultimately, the county relented, and carry-ins were allowed again through the end of the Braves’ tenure. But the team’s public support had been dented.

Rumors soon began to spread about a move to growing Atlanta, which offered a new stadium and a massive territory in the Southeast that stretched all the way to Houston in the west and Washington D.C. in the north. In an effort to keep the team in Milwaukee, Selig helped organize a group of civic leaders who offered Bartholomay’s group $7 million for a franchise that had sold for $5.5 million less than two years earlier. The offer was rejected. So Selig threw his support behind a lawsuit aimed at keeping the Braves in Milwaukee.

The effort succeeded only temporarily, delaying the inevitable for one year.

After a lame duck season in 1965, the Braves relocated to Atlanta.

“I was 13 years old when the Braves left,” Schabowski said. “I was old enough to appreciate what happened. I was blessed to be at Warren Spahn’s 300th win, I was at Lew Burdette’s no-hitter. I was at a lot of games. Still, when the Braves left Milwaukee, you knew it was coming.”

This browser does not support the video element.

Selig was particularly gutted. Attending the Braves’ final game, he remembers being approached by a woman in a wheelchair.

“She said, ‘Are you Bud Selig?’ and the poor lady had tears in her eyes,” Selig said. “She grabbed my arm and said to me, and I’ll never forget this, ‘Don’t you fail. You’re all we’ve got. Don’t you know how important baseball is to me?’

“I’ll never forget that feeling. She proved to me how important the game of baseball was and still is to its fans and the community as a whole.”

• • •

This browser does not support the video element.

The community eventually did get baseball back in 1970, when the Seattle Pilots moved to Milwaukee and became the Brewers with less than a week to go before Opening Day. For years, Selig had planned to clad Milwaukee’s new team in red and navy as an homage to the Braves, but in the end, there was no time for that. Selig ordered that the lettering and logos be pulled off the nautically-themed uniforms of the Pilots and hastily replaced with “BREWERS.” That’s why the Brewers wear blue and yellow to this day.

They went 65-97 that inaugural season, only one win better than their Pilots predecessors. It took four years to draw one million fans in a season, and when the Brewers slipped back under one million with another losing season in 1974, Selig began to worry. Aaron, meanwhile, had just broken Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record in '74 but was nearing the end of his career.

Selig had an idea. He began to work on a trade for Aaron, who could extend his career in the American League as a designated hitter while lending some credibility to the Brewers -- not to mention helping to sell some tickets. It came together on Nov. 2, 1974. In the only transaction of Aaron’s 25-year professional career, other than the day he signed with the Boston Braves, the Brewers gave up outfielder Dave May and Minor League pitcher Roger Alexander to bring Aaron back to where his big league career began 20 years earlier.

This browser does not support the video element.

“It was up to Henry,” said Bartholomay, who died last year. “After he broke the home run record in ‘74, which was momentous, which seemed to be untouchable, whatever Henry wanted to do, he could do. I was pleased with [the trade back to Milwaukee]. I wanted him to be happy.”

As Selig said of Aaron at the time, “He gave us instant credibility.”

At the 1975 home opener, more than 48,000 fans attended “Welcome Back Henry Day.” Aaron walked in the first inning, drove in a run with a groundout in the third and singled in the sixth for his first Brewers hit.

For the rest of his life, Aaron split time between Atlanta and Milwaukee before dying on Jan. 22 at age 86. As Aaron's teams prepared to meet in the postseason, Brewers manager Craig Counsell recalled a memorable meeting with the Hall of Famer at an event in Milwaukee some years ago, when moderator Bob Costas surprised Counsell by summoning him to the stage and Aaron surprised Counsell even more by beginning to ask questions about growing up playing baseball in a cold-weather city. Counsell was honored that Aaron cared to ask about his experiences.

“If you know Atlanta and Milwaukee, you know these are the cities he held near to his heart, so he would love this series,” Counsell said. “This would be Henry’s series, for sure.”