How Rizzo is using -- and not using -- the shift rules to excel

This browser does not support the video element.

Last year, Anthony Rizzo hit just .224, a career-low mark (excluding 2020). He did that while being shifted against on 83% of his plate appearances. He was, understandably, excited to learn that there would be limitations on shifts for the first time in 2023, saying, “I feel like I've been very affected by the shift, as are a lot of lefties around the league,” after re-signing with the Yankees in November.

This year, Rizzo is being shifted against 0% of the time, a 519-way tie for fewest shifts seen in the new baseball world. He’s now hitting .304, which would be a career high. His batting average on balls in play – that’s BABIP, which excludes strikeouts, walks, and homers, so just balls a fielder might be able to catch – is up 146 points.

It’s not hard to draw the connection, as many have. Rizzo is having something like a career year. The infield shift as we once knew it no longer exists. He’s a slow-footed lefty pull hitter. That’s the end of the story. Correlation does imply causation. The shift was responsible for 80 points of batting average.

Right?

Not … exactly. The new rules haven’t hurt, to be sure. Yet it’s about a lot more than that, too, because Rizzo has just three pulled ground ball hits in 2023. It’s about the infielders, but it’s also about the outfielders. It’s mostly about Rizzo, just hitting the ball better – and higher, and less often – than he ever has before.

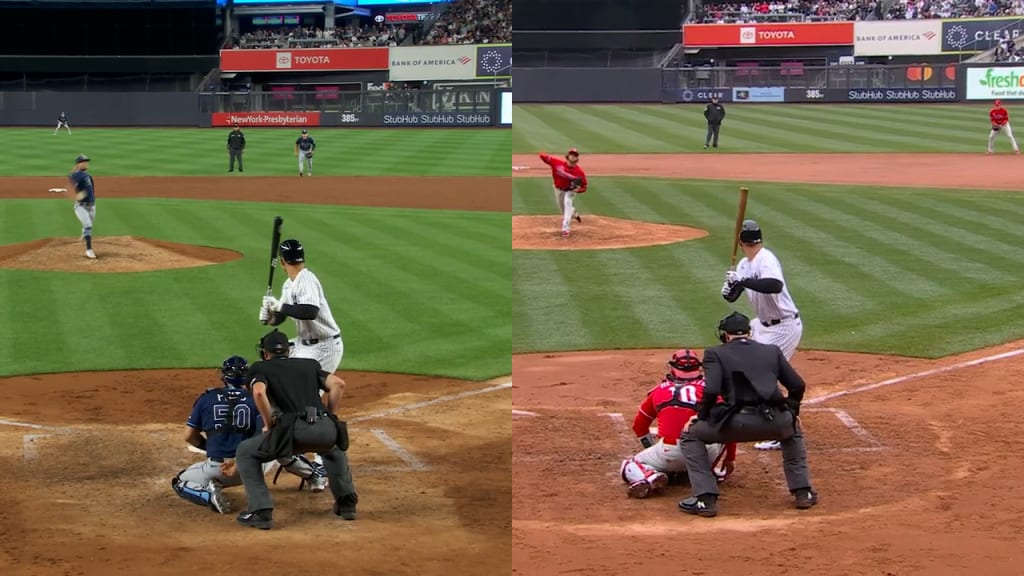

Certainly, we can’t and won’t pretend the shift limitations haven’t helped Rizzo at all, because all it takes is to look at an example of two very similar batted balls of his at Yankee Stadium – one from last year, one from this year – that had two very different outcomes. This is exactly what Rizzo and lefty hitters like him had in mind coming into the year.

This browser does not support the video element.

Left-handed batters, as a group, have had their BABIP rise on grounders by 10 points from last year, getting them back to where they were in 2018, and by 28 points when pulling the ball. Rizzo is no exception; he’s seen gains in those areas as well.

That part isn’t surprising; it was expected. What’s somewhat less expected is this: Rizzo’s performance is up _everywhere_, not just to the pull side. When pulling: A career-high .333 BABIP. When going up the middle: A .311 BABIP, which is his best since 2019. When going to the opposite field: A massive .486 (!) BABIP, which would not only be a career high, but is the fourth-highest of any player this season.

This browser does not support the video element.

That part – getting a hit nearly half the time he goes to the opposite field – probably isn’t going to last. (Rizzo, last year, had 18 hits to the opposite field all season. This year, he already has 17. It’s the last day of May.)

Then again, it doesn’t seem like a coincidence, either; he’s pulling the ball just 40% of the time, which would be the lowest rate of his career since way back in 2012, his first season with the Cubs. Is it possible that after all these years staring into the teeth of the shift, he’s finally decided to do what everyone had been shouting for all that time – go opposite field to beat the shift! – only after the shift is gone?

"It’s just where I'm hitting it, I guess," Rizzo said when asked by MLB.com's Bryan Hoch prior to Tuesday's game in Seattle. "I don't know. I'm not trying to do that. I'm just trying to hit it hard every time.”

If it was just that – more batted balls going to the opposite field over two months – we might say it was a fluke, or even evidence of an older slugger’s slowing bat. But there’s so much about Rizzo’s profile that seems different that it seems like a different hitter, intentionally or not. Consider this:

Rizzo is striking out a career-high 23% of the time, the first time he’s ever been over 20% aside from his brief 2011 cameo with San Diego

Rizzo is hitting grounders a career-low 29% of the time, the second straight year it’s declined from his usual ~40% range.

If you thought not having to deal with the shift would free up Rizzo to make more contact and not have to try to get it in the air as much, well, that hasn’t happened. (Which maybe shouldn’t have been a surprise; in April, speaking to The Athletic, he said that “even with no shift, my goal is to just have a really good at-bat and hit the ball as hard as I can.”)

It’s led to a 142 OPS+ that would be his best since 2016, when he finished fourth in NL MVP balloting and helped lead the Cubs to a championship. It’s just coming in a different shape than you might have expected.

The trick seems to be that he’s hitting the ball harder and in the air more – setting aside the strikeouts, he has a career-best quality of contact right now – but it’s also about the fact that what was ailing Rizzo in the previous few years wasn’t about the third infielder on the right side of the dirt as much as you’d think. It was about the fielders on the grass.

Forget about the infielders, just for a moment. Remember this kind of play?

This browser does not support the video element.

Seems like a right fielder, right? No: Whit Merrifield was in the lineup as the second baseman that day, playing in a spot so unfamiliar that the broadcast simply assumed he was right fielder Teoscar Hernández.

How about this one, where Rizzo flew out to a third baseman standing in a spot where absolutely no third baseman should ever be?

This browser does not support the video element.

Or this, where right fielder Bubba Thompson barely had to move a step? "Boy, the shift worked," the Yankees broadcast correctly noted.

This browser does not support the video element.

You don’t see those as often now, do you?

When looking into Rizzo’s numbers for this, one thing that struck us is that it’s not just about what happens when he puts the ball on the ground. It’s about what happens when he puts the ball into the air (at least 220 feet deep), yet not out of the park for a home run. So far this year, 35% of those balls from Rizzo are dropping for hits. Last year, it was 22%. You want a massive source of new hits? Here they are.

That’s because the often-forgotten tertiary aspect of the shift limitation behind “you can’t put three infielders on one side” and “you must have all infielders start on the dirt” is “you can’t have four outfielders,” and over the previous two seasons, no batter -- save for former teammate Joey Gallo -- faced a four-outfielder setup more often than Rizzo did – and no one had more long airball outs against it than Rizzo's 15.

While you can’t say all 15 were directly due to the setup, many certainly were; you don’t think of those when it comes to “the shift is banned,” but they matter, too.

This browser does not support the video element.

At the end of the day, it’s not that the shift limits aren’t helping him, particularly in unquantifiable ways like how his approach might be changed – if it is – by not having that extra fielder out there. It’s just that if it were as simple as “all lefty sluggers are getting helped equally” or “all of Rizzo’s gains are explained by the new rules,” then shift-affected lefty hitters like Kyle Schwarber and Max Muncy might not be running career-low BABIP marks.

What it comes down to is that Rizzo is hitting differently, and better, and more all over, even if he’s hitting it less often. He’s doing it against defenses that are less optimally positioned to stop him. It wasn’t hard to think that Rizzo’s approach might change in a post-shift world, or that he would find success. It just is more than a little surprising to find that he’s doing it in this way.